Many Reasons for Loyalty

There is a saying that “history is written by the victors,” which means the people who win wars often write history to favor their views. Perhaps this is why colonists who chose to support England during the American Revolution, called “Loyalists,” are misunderstood today. They were painted as bad people by many early American historians. In reality, many Loyalists had honorable motives, such as a preference for order, or for peace, or a critical one: the simple belief the colonies could not win.[1] Though also called “Tories,” for the British political party that backed punishing the American rebels, not all Loyalists were actually part of the party or supportive of its colonial policies.

In some cases, honor was the motive. Keeping your word and paying your debts were very important in those days. You could be shunned by your peers or even jailed if you did not do so. As an example of the former, Scots were allowed to emigrate to America only if they took an oath to support the British monarch. The oldest among them may have taken one after losing the Battle of Culloden Moor in 1746, ending the last Scottish rebellion against England. Even if they supported the idea of independence, their sense of honor made most of them fight on the other side. Scotsmen led the Tory attack at the 1776 Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge.

Another example is former Regulators, who protested against unfair and corrupt practices of the North Carolina colonial government ten years before the Revolution. After their defeat in the 1771 Battle of Alamance, nearly 6,000 of them took a similar oath. Keeping that oath was a reason for many to stay loyal. Not all did.

Many merchants depended on trade with Great Britain, and had debts they could not pay off, or collect from England, without that trade. So they and some large landowners across the state remained loyal partly for that reason.[2] Another was religion. Anglicans—members of the official Church of England—did not like the fact the church had lost its status in America. In North Carolina, the state stopped government financial support of the church and allowed other Christian ministers to marry people. This caused the largest Tory plot against the N.C. government, the Gourd Patch Affair.

German immigrants to N.C., whose homeland was connected to England through intermarried royal families, tended to be either loyal or neutral like the Moravians, many of whom still spoke German.[3]

There were less high-minded reasons for staying loyal, however. Many immigrants had been officers in the British army; some in the state were living on pensions of half their former pay.[4] Money played a role in attracting a number of the 1,600 Loyalists who showed up in Cross Creek (Fayetteville) for the Moore’s Creek campaign. The king’s government promised they “would supply them with arms and the same pay as the regular troops, and they would be ‘liberally paid’ for horses and wagons they brought with them.” Back taxes would be forgiven, and they would be given land after royal control was re-established. When the British invaded the state five years later under Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis, Royal Gov. Josiah Martin made similar promises as the commander of the Loyalist corps.

By the Numbers

Founding Father John Adams of Massachusetts famously estimated that only one-third of Americans wanted independence, with another third each loyal or neutral. A 1940 historian believed North Carolina probably had more Loyalists by percentage than any other colony. Contemporary and 19th-Century estimates of the percentage ranged from one-half to two-thirds loyal, he said.[5] In 1781, the Southern Continental Army commander, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, thought the number in N.C. was up to a half overall, and estimated Tories dominated about half of the N.C. counties. Even after the conclusive Redcoat defeat at Yorktown, Va., in 1781, there were 2,000 Loyalists receiving British pay in the state.[6]

Founding Father John Adams of Massachusetts famously estimated that only one-third of Americans wanted independence, with another third each loyal or neutral. A 1940 historian believed North Carolina probably had more Loyalists by percentage than any other colony. Contemporary and 19th-Century estimates of the percentage ranged from one-half to two-thirds loyal, he said.[5] In 1781, the Southern Continental Army commander, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, thought the number in N.C. was up to a half overall, and estimated Tories dominated about half of the N.C. counties. Even after the conclusive Redcoat defeat at Yorktown, Va., in 1781, there were 2,000 Loyalists receiving British pay in the state.[6]

An Elon University historian pointed out “that the cultural, economic, occupational, racial, ethnic, class, religious, and age backgrounds of the Loyalists” were the same as those of the rebels. Claims made for damages after the war suggest about half of North Carolina Tories were farmers, 30% owned shops or related businesses, and 11% held government offices—similar to the numbers for the rebels.

Like the rebels, Tories first tried peaceful means to protect their interests. At the same time budding patriots were creating petitions against the king’s actions, like the Tryon Resolves, Loyalists sent statements of support from the counties of Anson, Guilford (116 signatures), Rowan, and Surry (194 signatures).[7] The highest known number of signatures on a rebel petition in N.C. was 55 on the Liberty Point Resolves![8]

Tensions Rise

In a way, Loyalists and Patriots were not that far apart on the general desire to remain British. They just differed on the terms for doing so. Adams wrote after the war: “‘There was not a moment during the Revolution, when I would not have given every thing I possessed for a restoration to the state of things before the contest began, provided we could have had a sufficient security for its continuance.’” Founding Fathers Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington all said they heard no one talk of independence prior to 1775. John Madison said sometime after 1776, “‘a reestablishment of the Colonial relations to the parent country, as they were previous to the controversy, was the real object of every class of the people, till the despair of obtaining it…’”[9]

In a way, Loyalists and Patriots were not that far apart on the general desire to remain British. They just differed on the terms for doing so. Adams wrote after the war: “‘There was not a moment during the Revolution, when I would not have given every thing I possessed for a restoration to the state of things before the contest began, provided we could have had a sufficient security for its continuance.’” Founding Fathers Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington all said they heard no one talk of independence prior to 1775. John Madison said sometime after 1776, “‘a reestablishment of the Colonial relations to the parent country, as they were previous to the controversy, was the real object of every class of the people, till the despair of obtaining it…’”[9]

Many people wavered; it is one thing to disagree with your king, and another to take up arms against him. Regulators fought on both sides during the Revolution, as did members of the colonial army that defeated them. Two signers of the 1775 Liberty Point Resolves fought as Loyalists.[10] Both sides were represented among the state’s militia in the next year’s campaign against the Cherokees. And some people switched sides in the Revolution, by choice, a few more than once! (Others were forced to make the change.)

A year later the new state of North Carolina and its county courts, which in those days were also the county governments, took increasingly strong actions against the Tories. “A common punishment was publishing names of suspected Loyalists in local newspapers,” an historian writes. “Citizens were to ‘break off all dealings with him or her.’” For many, this became a license to steal. “In the hills when the news spread abroad that a neighbor had joined the enemy the community would descend upon the worldly goods left behind—one would take a chair, a table, or a ‘skillet,’ another would make a selection from whatever wearing apparel could be found, and a more fortunate one would carry off a feather bed.”[11] Eventually the state had to pass laws against people taking Loyalist property, at the same time it was passing other ones to do so legally (see the next tab). But even enforcers of legal “confiscation” were prone to corruption, selling it below value and to themselves, such that sales were suspended in January 1781.

By 1779, Loyalists were pushing back. In the most famous incident, the Gourd Patch Affair, a group tried to attack the jail at Tarboro, and plotted to capture Halifax and install a Loyalist constitution for the new state. At least two other groups formed to resist the state’s draft of soldiers for the Continental Army, one of which planned to raid the arms stored at Kinston or the Smithville jail, though it’s unclear whether these were Loyalists or neutrals.

Legal Troubles

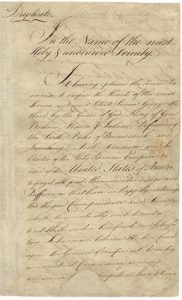

On July 4, 1776, not aware of events that day in Philadelphia, the temporary council running North Carolina ordered everyone suspected of Loyalism to provide inventories of their property.[12] Any who refused would be arrested and brought for trial before the council. The next April, the new state legislature approved a law that defined some acts against the state as treason, for which the guilty could lose their lives and their property. Others who just helped the British or spoke in their favor could be charged with a lesser charge, “misprison of treason,” and face imprisonment and loss of half their property. Those who had been British officers or done business with Great Britain within the prior year were required to take an oath of allegiance and agree to defend the state, except sects like the Moravians or Quakers. Those who refused could be brought to court, and if they still refused, banished from the state with 30 days’ notice.

Many left on their own. Alexander Hamilton of Halifax bought a boat to take him and friends to British-held New York City.[13] Alexander Telfair’s ship for that purpose became known as the “Tory Brig.”

But the state tightened the screws over the next few years:

- Late 1777: The oath requirement was expanded to cover all males 16 or over. Though refusers might be allowed to stay in the state, they essentially gave up all legal rights. Only a small percentage of people actually showed up to take the oath, and many Patriots (“Whigs”) objected that the crackdown on Tories was too harsh. So provisions were passed the next year protecting the families of Tories and making it possible for confiscated lands to be recovered.

- 1779: With the war dragging on, however, a new law confiscated properties of suspected Loyalists who were absent from the state on the original Independence Day or who left afterward, and widows were allowed only a third of the property.

By September 1780, county jails were stuffed with Tories. The legislature allowed them to be tried by local judges without a defense lawyer or juries of their peers, and hung if found guilty!

At least they got trials. N.C.’s Col. Benjamin Cleveland was indicted for murder after one of his many hangings of Tories without that benefit. Not surprisingly, given his military history and social status, he was never brought to trial either.

Tories at War

During the war Loyalist militia soldiers served many of the same purposes for the British as Patriots did for the Continental armies, using their local knowledge “as scouts, spies, messengers, guides and waggoners.”[14] When the British invaded North Carolina in 1781, many Tories were emboldened to rise and join them, such as Col. John Pyle of Chatham County. He had returned to farming after escaping captivity in the aftermath of the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge. In 1781 he led 300 men toward Cornwallis’ camp, but they did not make it. Around this time, three of seven Dobbs County state militia regiments defected to the British.[15]

Col. Samuel Bryant, from the Shallow Ford area west of modern Winston-Salem, was able to raise around 800 Loyalist militia—for comparison, that is as many as the number of N.C. Patriots who fought at the Battle of Guilford Court House. His force conducted numerous anti-Whig actions from his local area down into South Carolina.

No doubt the most famous, or infamous, Tory in North Carolina was David Fanning. Starting out as an independent partisan leader, in the Summer of 1781 he was named a colonel in charge of Loyalist militia in two counties by the British. Along with actions considered war crimes today, such as the murder of Andrew Balfour in his home in front of his young daughter, Fanning also pulled off one of the most daring raids anywhere in the war, kidnapping the governor.

Overall, though, Patriot partisans were more effective. Adding up head counts from various battles lost by Tories prior to the Race to the Dan, one writer suggests Cornwallis could have attracted as many as 3,200 Loyalist militia during his 1781 campaign had those been won or avoided.[16] This would have more than doubled the number of fighters he had at Guilford Court House. Instead, no Loyalist militia are known to have fought there.

Historians suggest the British did not understand the pressures Tories were under in the South, from Patriot militia and unofficial partisans, and did not make good use of them. After the British recaptured Charleston in 1780, Cornwallis issued orders that most men 18 to 40 serve up to a year anywhere in the South, though some were allowed to form a home guard staying in their areas. This had the effect of driving many former neutrals into Whig camps.[17]

Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton and Maj. Patrick Ferguson realized Tory militia could be more useful if formed into “provincial troops” trained and equipped like their regular army peers. A modern-era lieutenant colonel points out that the high degree of training provided to Redcoats—on coordinated movement and calm under fire, for example—made it difficult to incorporate short-term, volunteer partisans.[18] However, Cornwallis seemed to think they should be able to form effective units on their own and control large areas without British help. He also refused to accept into service those who had fought alongside the rebels at any point, which made raising Loyalist forces difficult, especially suitable officers[19]: Rebels often forced captured Tories to fight in their militias, following the modern movie quotation, “Keep your friends close and your enemies closer.”[20]

As a historian summarized in his dissertation on southern Loyalists:

“The British policy was to not allow any former rebels into the militia, but in practice they had little idea of who anyone was among the population, and allowed former rebels to infiltrate the militia without realizing they were doing so. They vacillated between emphasizing the development of local militia and forming provincial corps, initially choosing the former, but giving the militia little of the support it needed…”

“The rebels, meanwhile, continued the strategy that had served them from the beginning of the war. As (Patriot Brig. Gen.) William Lee Davidson described it, the rebels could not risk a frontal confrontation with the British army, but there was always something they could do to disperse parties of Loyalists before they could assemble and provide service to the British.”[21]

Examples you can visit using our site include the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill, the Battle of Raft Swamp, and Col. John Pyle’s Defeat.

Three Lives

Archibald Nielson

Archibald Nielson is an example of a Loyalist who had friends on both sides but ultimately chose what he saw as the higher value of public order. A Scot who had spent time in the West Indies, he was close with the last colonial governor, Josiah Martin, and lived at Tryon Palace with him at times. He arranged the ship that took Martin’s family to safety in New York as problems got worse with local rebels, and accompanied Martin when the governor finally fled to Fort Johnston (today’s Southport) in 1775. Yet Patriot leaders James Iredell and Samuel Johnston of Edenton counted him as a friend. A historian said “Neilson declared to Iredell that he was a friend of liberty and just authority but an enemy of anarchy.”

Nielson was part of the colonial militia, but refused to join the Patriots who marched on and burned the fort in July 1775. For that, he and others were threatened with trial for treason by the temporary rebel government. Martin was living on a Royal Navy warship, the Cruizer, by then, and Nielson joined him there. According to a Scottish woman who befriended Nielson during her visit to North Carolina, Janet Schaw, he had “no place to sleep in aboard, but lies on the quarter-deck in his hammock, as do many more Gentlemen, as it is quite crouded [sic].”[22]

Serving as a personal secretary to Martin, he wrote out Martin’s proclamation calling on Loyalists to join them and help the British army retake control of the colony, which led to Moore’s Creek. Nielson’s groom was one of the men sent out with copies, and Schaw tells what happened to him. The groom, “who was a most expert rider, was mounted on a fine English hunter (horse), the commissions put into the travelling bags before him, under cover of his own linens, and fixed to the crupper (pommel); in a leather case were the two proclamations.” He traveled two days without trouble, but on the third happened to pass some local Patriot leaders who took notice of his fine horse and chased after him. Schaw continues:

“(He) quitted the road and struck into the woods, where trusting to the superior swiftness of his mare, he put her full speed, and in a few moments would have left his pursuers far behind, but, alas…

“A tree struck her or rather she a tree so violent a blow, that she fell to the ground, and threw her unfortunate rider with the bags, and before he could get hold of the bridle, scampered off most unluckily, carrying with her the two proclamations, which were fixed to the saddle. The fellow however had the presence of mind to bury the commissions in the sand, then running to a distant part of the wood, he let the bags lie on the ground, as if thrown by the mare, and laid himself down as half killed by the fall.”

Under questioning he said nothing, but one of his pursuers found the papers, and he was taken to Wilmington to appear before the Committee of Safety that was operating as the local government by that point. They burned the papers in anger, but the groom was able to escape to the house Schaw was living in, where he recounted his tale.[23]

Schaw herself was eventually forced to make a dramatic escape down the river to the Cruizer with her Loyalist hosts. She, a sick Nielson, and others left for Portugal from there on a ship that came in with new Scottish emigrants. Nielson recovered his health, went to London, and from there went to New York as a volunteer helping the British army. However, he had to return to Scotland after his brother died, where he became a merchant to support family members.[24]

A historian recorded in 1921 that Neilson “wrote that he might be called ‘a devilish unlucky fellow;’ for, save friends, he made nothing while in America, had recovered nothing of the Government for his losses, and was still unmarried.” He had also been forced to leave in North Carolina a trunk containing letters from his father, who died when he was four.[25] Nielson never married, but he did get eventually get a British government pension for his service.[26]

Thomas Peters

Though descendants claimed he was of royal Yoruba birth and kidnapped from Africa, records suggest Thomas Peters was born into slavery on a plantation near Wilmington. He was 38 when he escaped in 1776, apparently having heard about the Virginia governor’s declaration that people held by rebels who became Loyalist soldiers would be freed.[27] Details of what must have been a dramatic journey are unknown, but somehow he made it to British-held New York City.

There he became one of 60-70 Black Pioneers, a unit of former slaves. “Black residents of the countryside in which the British were fighting would have been invaluable because they had intimate knowledge of the landscape and its hazards, the trails and shortcuts, the streams and marshes, and the hiding places and dangers.” Blacks succeeded as spies, messengers and at “leading sorties that captured rebels.”[28] The unit was led by white officers, but Peters became a sergeant with two other blacks. He was wounded twice. The Pioneers served in the campaign that captured Philadelphia in 1777, forcing the Continental Congress to flee.

Two years later a woman named Sally, 26, was able to make her way to New York from Charleston. She joined the Pioneers as well, where she met Peters, and they married.[29]

The 1783 Treaty of Paris officially ending the Revolutionary War included a clause that said the British would remove their military without “carrying away any Negroes or other Property of the American Inhabitants.” To the fury of slaveowners, the British commander in North America, Lt. Gen. Sir Guy Carleton, interpreted that to mean currently enslaved people. Certificates of freedom were issued to everyone within British lines as of a year before the treaty (when major fighting ended with the surrender at Yorktown), including Sally and Thomas.

The Peters left New York by ship in November 1783, including a 12-year-old daughter and toddler son. Their trip to Nova Scotia was prolonged by uncooperative winds that sent them first to Bermuda, so they did not arrive until May 1784. At least 3,400 black Loyalists were there by that Fall.[30] Peters was made responsible for 76 of them in the town of Digby on the north coast, where each family was supposed to get a one-acre lot. Those grants were delayed by either incompetence or corruption among British authorities. Meanwhile, the ex-slaves got only a few months’ worth of the three years of British rations they were promised, and unlike whites, blacks were forced to work on roads to get them.[31] Gardens, fishing, and charity helped keep families alive.

Peters and another former sergeant applied for farm grants promised to the soldiers upon their enlistments. After many delays, these was finally provided in 1788 in the new province of New Brunswick. However, Peters complained, the land was “‘so far distant from their Town Lots (being 16 or 18 Miles back) as to be entirely useless to them and indeed worthless in itself from its remote situation.’” Peters finally became a mill worker to feed his family.[32]

A black servant overheard a discussion among whites about a plan by a group in England to purchase land in Sierra Leone and give former slaves land there. Peters took a ship to London in 1790 with a petition asking the Crown either for the land promised them in Canada or to be sent elsewhere in the empire. He found his former commander, who recommended him to the former British commander-in-chief in America, who in turn sent him to Granville Sharp, head of The Sierra Leone Company.[33] Granville introduced Peters to other directors and the British Secretary of State. The latter ordered an investigation into the problems in Canada, but also sent Peters back with an offer of “free passage to the blacks in Nova Scotia who wanted to go to Sierra Leone.”

Many white Loyalists opposed the plan, fearful of losing the labor of the blacks in their underpopulated province. They spread rumors including that the company planned to sell people back into slavery, and that Peters was getting a cut of the profits.[34] Yet an unexpectedly high number of people signed up, 1,200. They left behind most of their belongings, and many waited weeks in uninsulated warehouses in late Fall 1791 while ships were fixed up for the journey.[35] A military style organization was finally put in place to manage the operation, with Peters second-in-command. The fleet of 15 ships finally sailed in January 1792, arriving in Freetown, Sierra Leone, two months later.

There Peters was stunned to learn that the settlement had been changed from a charitable operation to be governed by blacks, as he was told, into a commercial venture run by whites sent from London. Almost as soon as they landed, tensions boiled over between Peters and John Clarkson, the white governor who had run the operation in Nova Scotia. Some people began pressing for Peters to take over.[36] When Peters was selected at an April meeting to present the settlers’ demands, Clarkson apparently took that as a coup attempt.[37] He confronted Peters at a meeting of the whole settlement, saying “‘it is probable that either one or other of us would be hanged upon that Tree before the Palaver was settled.” Eventually he was reassured Peters was not seeking to take over.

Soon after, however, Peters made the mistake of taking belongings of another former Pioneer after that man died. Arrested and tried in May, he claimed it was repayment for help Peters gave him in helping free the man’s wife from slavery years earlier. Peters was nonetheless convicted by a black jury, and forced to return the property and pay a day’s wages to the jury members.

As Clarkson tried to work out a compromise with the people over the colony’s government, Peters suddenly died of a fever in the night of June 25–26.[38] Clarkson ordered a pension for Sarah and her children. “‘Thos. Peters funeral went off without disturbance,’” he wrote, with “‘a great many’” attending.[39]

John Hamilton

The “North Carolina Volunteers” was the name of a Loyalist unit of full-time soldiers fighting with the British army.[40] Leading it was John Hamilton, who had immigrated from Scotland by 1760 and founded an import-export business in Virginia with his brothers. When the Revolution broke out, John was running a branch of the operation six miles southwest of Halifax at Hamilton’s Hill. After the war Hamilton’s children filed a claim for those properties, a foundry, various buildings, and four ships.[41]

The company also speculated in land, buying more than 7,000 acres in North Carolina[42], and made loans at a time when banks did not exist here—debts they were no longer able to collect by 1775, because the provincial court system had stopped operating. John and his brother Alexander, mentioned under “Legal Troubles,” refused to swear loyalty to the state as required by the 1776 law and were given two months to get out. They sailed with other Loyalists from New Bern to New York. Later they would claim they lost £200,000 as a result of leaving, equal to $35 million today![43]

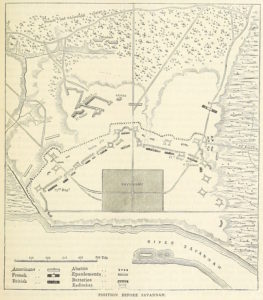

Around 30 of the men on that ship formed the North Carolina Volunteers and sailed south to help the British retake control of Georgia in 1778.[44] Hamilton had 90 sharpshooters at the Siege of Savannah, a British victory, and was promoted to colonel there. [45] In March 1780, Hamilton was captured in South Carolina by the cavalry of Col. William Washington, a distant relative of Gen. George Washington.[46] It’s unclear if Hamilton was released or escaped, but he soon was back with the British.

Recruiters brought in more men when the unit joined Cornwallis’ army after it took Charleston. The regiment was left to guard the supply center at Camden (S.C.) during Cornwallis’ invasion of North Carolina that ended in Charlotte.[a] But one source says the N.C. Volunteers were in front when the next one was launched in 1781, leading to the Race to the Dan.[47] Another says it had 232 men by the time of the pivotal Battle of Guilford Court House two months later. But they were sent off to Bell’s Mill with the army’s wagons on the morning of the battle.[48] By the time the regiment surrendered along with Cornwallis at Yorktown (Va.) in October, it was down to 80 men.

Hamilton apparently was treated well in captivity because of his N.C. friends and his reputation for fairness to Patriot prisoners during the war.[49] He was paroled and went to Charleston before the British evacuated the next year. After the evacuation the regiment was combined with some other Tory units, including the Black Pioneers, as the Royal North Carolina Regiment. This was transferred first to the English colony of East Florida, which had not joined in the American Revolution, and then to Nova Scotia.

That province in eastern Canada, which also had not sought independence, was where many N.C. Tories ended up, including the infamous Col. David Fanning. Hamilton went on to London, but returned to Virginia in 1790 as the British consul! A visiting Irish poet said Hamilton was “‘one among the very few instances of a man, ardently loyal to his King, and yet beloved by the Americans. His home is the very temple of hospitality…” Hamilton went back to England as the War of 1812 broke out, and died there four years later.[50]

After the War

Tory legal troubles did not stop with the Revolutionary War. The Treaty of Paris that ended hostilities in 1783 included a clause saying Loyalists were to have their properties returned. A North Carolina law openly defied the treaty the next year, by allowing all remaining confiscated property to be sold. Properties already sold had come with guarantees to the titles for the buyers, making them impossible to return.[51]

A few N.C. Loyalists, all of them likely living in England by that point, were given pensions or compensation by Great Britain. Chief among them were the last Royal governor, Josiah Martin. Others included Moore’s Creek leaders Alexander and Donald MacDonald, and the widow of Alexander McLeod, who was killed in the attack; Alexander Telfair of the Tory Brig; Edmund Fanning, the man most hated by the Regulators; and William Brimage of the Gourd Patch Affair.

Despite the long history of hatred between Tories and Whigs, Alexander Hamilton and Nathanael Greene were among leading Patriots who argued for forgiveness of Loyalists.[52] N.C. Patriot leader and later U.S. Supreme Court Justice James Iredell wrote in 1784: “‘No man is good or bad merely for his opinions; in political questions there is room for almost an infinite diversity of sentiment, among even the wise, as well as men of little understanding; and no man in a civil war is justly censurable for anything but insincerity in choosing his side, or infidelity in adhering to it.’”[53]

In other words, even their former opponents realized most Loyalists had fought for their honestly held beliefs, just like the Patriots, and deserved a degree of respect so long as they did so honorably.

More Information

- Burke, William, ‘The North Carolina Loyalists: Faulty Linchpin of a Failed Strategy’ (unpublished Master’s thesis, The College of William and Mary, 1988)

- Clark, David, ‘Nolan and Vardey: Resolves Signers Fought with Loyalists’, The Fayetteville Observer and the Fayetteville Times (Fayetteville, N.C., 15 February 1976)

- Clark, Murtie June, Loyalists in the Southern Campaign of the Revolutionary War, Vol. I (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1981)

- Coldham, Peter, American Loyalist Claims (Washington, D.C.: National Genealogical Society, 1980), I

- Conner, R. D. W., North Carolina: Rebuilding an Ancient Commonwealth, 1584-1925 (New York, NY: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1929)

- DeMond, Robert, The Loyalists in North Carolina During the Revolution (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1940)

- Dziennik, Matthew P., ‘Through an Imperial Prism: Land, Liberty, and Highland Loyalism in the War of American Independence’, Journal of British Studies, 50.2 (2011), 332–58

- East, Lt. Col. Jackie, Lessons from the British Defeat Combating Colonial Hybrid Warfare in the 1781 Southern Theater of Operations (Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2014)

- ‘Extracts from the Pennsylvania Packet, March 27, 1780 Volume 15, Page 386’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1780 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr15-0288> [accessed 26 January 2022]

- Harrell, Isaac, ‘North Carolina Loyalists’, North Carolina Historical Review, III.4 (1926), 575

- Johnson, Talmage, and Charles Holloman, The Story of Kinston and Lenoir County (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton Company, 1954)

- Johnson, Uzal, Uzal Johnson, Loyalist Surgeon: A Revolutionary War Diary, ed. by Bobby Gilmer Moss (Blacksburg, S.C: Scotia Hibernia Press, 2000)

- Lehman, Sarah, tran., ‘Isaac Farlow’s Statement of Revolutionary Events’, North Randolph Historical Society Quarterly, II.III (1968)

- Lewis, J.D., ‘Forks of the Yadkin’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2011 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_forks_of_the_yadkin.html> [accessed 14 March 2022]

- ‘Loyalist Institute: An Introduction to North Carolina Loyalist Units’ <http://www.royalprovincial.com/military/rhist/ncindcoy/ncintro.htm> [accessed 23 July 2021]

- MacKenzie, Roderick, Strictures on Lt. Col. Tarleton’s History ‘of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America’ (London: Printed for the Author, 1787)

- Morrill, Dan L., Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution (Baltimore, Md.: The Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1993)

- Pruitt, Albert Bruce, Abstracts of Sales of Confiscated Loyalists’ Land and Property in North Carolina (Rocky Mount, N.C.: A.B. Pruitt, 1989), Durham Main Library, North Carolina Collection

- Raynor, George, Patriots and Tories in Piedmont Carolina (Salisbury, N.C.: Salisbury Printing Co. Inc., 1990)

- ‘Revolutionary War Loyalist History and Genealogy’ <http://www.royalprovincial.com/> [accessed 27 July 2022]

- Sabine, Lorenzo, Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution: With an Historical Essay (Boston : Little, Brown and Company, 1864), Vol. I <http://archive.org/details/biosketchloyal01sabirich> [accessed 18 May 2022]

- Sabine, Lorenzo, Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution; with an Historical Essay (Boston, Little, 1864), Vol. II <http://archive.org/details/biographicalsket02sabiuoft> [accessed 24 September 2022]

- Smith, Jr., Claiborne, ‘Telfair, Alexander’, NCpedia, 1996 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/telfair-alexander> [accessed 2 August 2021]

- Stumpf, Vernon, ‘Neilson, Archibald’, NCpedia, 1991 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/neilson-archibald> [accessed 3 June 2022]

- The Edgecombe County Heritage Book Committee, Edgecombe County Heritage, North Carolina, 1735-2009 (Waynesville, N.C.: Walsworth Publishing Company, 2009)

- ‘The Loyalist Pages’, Org <https://www.americanrevolution.org/loyalist.php> [accessed 27 July 2022]

- Troxler, Carole Watterson, The Loyalist Experience in North Carolina (North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1976), Durham Main

- Troy, Daniel, ‘Ruining the King’s Cause: The Defeat of the Loyalists in the Revolutionary South, 1774–1781’ (unpublished Dissertation, The Ohio State University, 2015)

John Hamilton (additional)

- Dickens, Jeff, ‘Halifax, NC, E-Mail’, 22 September 2021

- ‘Hanging Rock’, American Battlefield Trust, 2017 <https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/hanging-rock> [accessed 23 July 2021]

- ‘Marker: G-56’ <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=G-56> [accessed 23 July 2021]

- Troxler, Carole, ‘Royal North Carolina Regiment | NCpedia’, 2006 <https://www.ncpedia.org/royal-north-carolina-regiment> [accessed 23 July 2021]

- Troxler, Carole, and Arthur Menius, ‘Hamilton, John | NCpedia’, 1988 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/hamilton-john> [accessed 23 July 2021]

Tom Peters (additional)

- Clifford, Mary Louise, From Slavery to Freetown: Black Loyalists After the American Revolution (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1999)

- Hatch, Richard, ‘Patriot Freedom Rhetoric Encouraged Slaves to Join Armies of the Americans and British’, The News and Observer (Raleigh, N.C., 4 July 1976)

- St G. Walker, James, ‘Peters (Petters), Thomas’, in Dictionary of Canadian Biography (Toronto: University of Toronto/Université Laval, 1979), 4 <http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/peters_thomas_4E.html> [accessed 25 June 2022]

[1] Sabine 1864 (I).

[2] DeMond 1940.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Burke 1988.

[5] DeMond.

[6] East 2014.

[7] DeMond.

[8] The number of signatures on the best-known Patriot association, the “Mecklenburg Resolves,” is unknown. Given that Mecklenburg County’s population was smaller and more dispersed than that of Cumberland in 1775, the number was probably smaller than Liberty Point’s.

[9] Sabine.

[10] Clark 1976.

[11] Burke.

[12] Conner 1929.

[13] Morrill 1993.

[14] Burke.

[15] Johnson and Holloman 1954.

[16] Sherman 2007.

[17] East 2014.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Burke.

[20] Though similar ideas appear as far back as the ancient Chinese text The Art of War, the exact quotation is from The Godfather: Part 2.

[21] Troy 2015.

[22] Stumpf 1991.

[23] Schaw 1921.

[24] Stumpf.

[25] Sabine 1864 (Vol. II).

[26] Stumpf.

[27] St. G. Walker 1997.

[28] Clifford 1999.

[29] St. G. Walker.

[30] Ibid.

[31] St. G. Walker.

[32] Clifford.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] St. G. Walker.

[38] Fever: Ibid.

[39] Clifford.

[40] Troxler 2006.

[41] Coldham 1980.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Troxler and Menius 1988; currency conversion: Nye, Eric, ‘Currency Converter, Pounds Sterling to Dollars, 1264 to Present’ https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm.

[44] Troxler 2006.

[45] Russell 1965.

[46] ‘Extracts’ 1780.

[47] Russell.

[48] Burke.

[49] Russell.

[50] Troxler and Menius.

[51] Conner.

[52] Sabine (V. I).

[53] James Iredell to A. Neilson, 6/15/1784; quoted in Harrell 1926.

[a] MacKenzie 1787.