Whigs Gamble 100s to Save 20

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.4779, -81.2628.

Type: Sight

Tour: Race to the Dan

County: Lincoln

![]() Partial

Partial

The coordinates take you to the parking lot behind Battleground Elementary School in Lincolnton, off Paul Lawing Drive. If that lot is full, return to Lawing, turn right, and turn right again on Jeb Seagle Drive. After a couple of curves there is a parking area visited later on the tour on the left, and another lot on the right in front of the school. From either, walk behind the school to start the tour.

Context

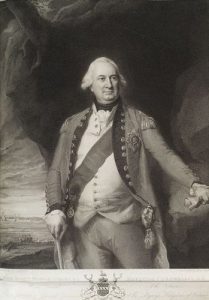

The British commander in the South sent Loyalist Lt. Col. William Moore to North Carolina to recruit local volunteer troops for a planned invasion by the British from South Carolina.

The British commander in the South sent Loyalist Lt. Col. William Moore to North Carolina to recruit local volunteer troops for a planned invasion by the British from South Carolina.

Situation

British/Tory

Moore was ordered by Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis not to gather his recruits in one place yet. Instead Cornwallis wanted these volunteers, mostly farmers, to focus on providing grain to feed his army. However, Moore heard that Col. Griffith Rutherford was gathering Patriot part-time “militia” troops to oppose his efforts. Moore called on Loyalist (“Tory”) companies and individuals to join him at Ramsour’s Mill on Clarke’s Creek, now in Lincolnton. About 1,300 camped on a ridge across the creek, though 300 did not have guns.

Patriot

Col. Francis Locke’s forces were sent by Rutherford, who was south of Charlotte, to keep an eye on Tories in this area. Locke gathered 400 Patriots 16 miles to the northeast after hearing about the Tory camp. Though aware Moore’s force was much larger, he notified Rutherford and decided with the other officers to attack anyway: The Tories had captured 20 Patriots (“Whigs”) and planned to hang them the next day.[1] After marching overnight, two miles east of town they split their forces. Cavalry continued slowly but directly to the east end of the ridge, while the infantry moved to the south around a bog to the base.

Date

Tuesday, June 20, 1780.

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

Charging Out of the Fog

Walk to the highest corner of the parking lot, past the monuments on the right, and down the sidewalk. Take the curve to the right and stop where it straightens out. Face the high school below you.

As dawn breaks around 7 a.m., this ridge is covered with hundreds of frontiersmen and farmers asleep or starting their day. Only two officers, who had served with the regular British army, have uniforms. The flatter parts of the hill are farmland owned by Christian Reinhardt, so it is mostly open with a few trees. The ground is wet after a night of strong rain, and a heavy fog hangs about the hillsides.

As dawn breaks around 7 a.m., this ridge is covered with hundreds of frontiersmen and farmers asleep or starting their day. Only two officers, who had served with the regular British army, have uniforms. The flatter parts of the hill are farmland owned by Christian Reinhardt, so it is mostly open with a few trees. The ground is wet after a night of strong rain, and a heavy fog hangs about the hillsides.

Along the first part of the sidewalk you walked down—either under it or just to its left—in 1780, there is an unpaved “road” barely wider than a bridle path. It leads past the mill to the west of the ridge (behind you), and continues miles to the east to Sherrill’s Ford over the Catawba River. At least a half-mile ahead of you, you hear gunshots. Men scramble to their feet in confusion, grab their weapons, and form a line facing that direction, to your left and right across the hill.

The sidewalk below the curve seems to match where a second-hand report claimed the Tory line formed. More likely it was further downhill on part of the slope destroyed when the high school was built. Also, instead of curving back along the road the way the sidewalk does, the left end probably continued directly across the ridge.

First the “pickets” who had been guarding the road and fired the shots appear on horseback, galloping for their lives up the road and out of the fog. Then off the left side of the road you see what they are running from: Patriot cavalry! Those horsemen are charging straight up the ridgeline, perhaps hoping they still have the advantage of surprise.

Look left to spot the top of the ridge, and then let your eyes follow down to where the ridgeline would have run above the high school.

When the Patriots are close enough to emerge from the fog, somewhere within 50 yards, the Tory line fires a volley. Some of the cavalrymen drop. Capt. Galbraith Falls, a veteran of the 1776 Cherokee Campaign, is hit in the chest. The rest wheel around and turn back out of range. Falls rides back down the road to the base of the hill and falls off his horse, dead. Then you hear a commotion to your right.

Turn right and look downhill to Lawing Drive. It’s unclear whether a road was there at the time. Bushes lined the small stream at the base then as they do today, though probably thicker. Where you see houses to the left was a swamp, and today’s Battleground Road that passes them from the right was another dirt road. See the map at the bottom of the page (spoiler alert!).

Patriots on foot are running up the road (Battleground) and pouring off it in both directions, toward you and out of sight to the right. They, too, are reacting to the surprised shots from the Tory pickets. Their officers had hoped the infantry would be in place before the cavalry attacked. They try to form a line on the near side of the stream.

A Hillside Covered in Blood

Look in both directions around the ridge above and behind you.

Not knowing where all the Patriots are, or how many, more Tories are rushing to extend the line you are in. Unlike regular armies, militia are not well drilled or organized, so men rush into line wherever they see fit, leaving clumps of people and gaps in both armies. Soon, though, the Tory line begins to curl along both sides of the ridge into a “U” shape, with the bottom of the U facing the direction of the first horse attack. It would have snaked back uphill from you along the sharp edge you passed on your right when you first walked down the sidewalk (behind the monuments).

Not knowing where all the Patriots are, or how many, more Tories are rushing to extend the line you are in. Unlike regular armies, militia are not well drilled or organized, so men rush into line wherever they see fit, leaving clumps of people and gaps in both armies. Soon, though, the Tory line begins to curl along both sides of the ridge into a “U” shape, with the bottom of the U facing the direction of the first horse attack. It would have snaked back uphill from you along the sharp edge you passed on your right when you first walked down the sidewalk (behind the monuments).

A Patriot officer wrote later: “In some places they were crowded together in each other’s way; in other places there were none. As the rear came up they occupied those places, and the line gradually extending, the action became general and obstinate on both sides.”[2]

Look back down toward the stream.

The Whig infantry begin rushing up the hill here and around the corner to the right without a good formation. The Tories pour random fire into them and the Whigs fall back. Officers are yelling at them, trying to form them into a good line.

Hearing this, the Tories decide to charge. (Maybe officers yell for them to, or maybe some just take off and others follow.) Everyone around you runs downhill, attempting to break the Patriots up. Not having bayonets or wanting direct combat, they likely pull up when they can see the enemy through the mist, maybe halfway down the hill. For about an hour, the two sides continue firing at each other as the fog lifts.

Finally the Tory officers decide to pull back. They yell orders and the line retires up the hill past you and over the summit. The Patriots, encouraged by this, follow them up past you. But the relatively sharp ridgeline gives the Tories cover while the Whigs are exposed to their fire.

Turn around and imagine seeing at the top of the ridge only heads, shoulders, and pointed at you, muskets!

The Whigs fall back downhill and take cover behind the bushes at the edge of the swamp. (Some sources say these are around a “glade,” but more likely they are along the stream, and the “glade” refers to the flat where another stream comes in near the intersection of Battleground and Lawing.)

Encouraged, the Tories attack back down the hill again, and the continuous exchange of fire renews. However, another Whig company under Capt. William Hardin enters the field out of sight to your right. It forms a line and concentrates fire on the right flank of the Tory line, on the far west end of the hill (described below).

Also out of sight of you, on the other side of the ridge behind you, another set of Patriots have moved around to the north, as we’ll see later. Pressed on three sides, the Tories fight back, and the battle dissolves into a hand-to-hand melee all around you. Neighbors knowingly attack neighbors; in at least two cases, one brother purposely kills another. There are no uniforms, and the only markings separating the two sides are pine twigs in their hatbands for the Tories and bits of white paper for the Whigs. It’s likely some people killed others from their own sides, “‘and as the smoke would blow off from time to time, they would recognize each other,’” one participant said.[3]

Fifty-five years later, Christian Reinhardt’s 17-year-old grandson Wallace wrote down stories he had heard from his family and Patriot scout Adam Riep. According to him:

- Riep and a Tory who had offended him in days past spotted each other and raised their guns. The Tory got off a shot first, but hit Riep’s bullet pouch, breaking it but sparing him. Riep was able to reload first and killed the Tory. Riep claimed to have killed several Tories, while suffering only a bruise.

- During the hand-to-hand fighting, Riep claimed he spotted three Tories heading toward Locke. He knocked one down and clubbed another with his rifle, apparently breaking the stock off. The third hit him hard on the shoulder, but Riep’s brother killed that man.

- 17-year-old Nicholas Hafner was clubbing at everyone. Riep intervened, and Hafner supposedly said, “By damn, them fellows has lost them pine tops from their hats and I can’t tell which is which or who is who.”

- A 12-year-old boy followed the Patriots to watch the battle and climbed a tree at the base of the hill. He tried to hide behind the trunk when bullets began flying but was hit and fell, two fingers gone.[4]

Lt. Samuel Patton arrived with Rutherford just after the battle. He later reported, “The battlefield was a terrible sight—there was bodies strewn about the hill which was soaked in blood.” It was clear to him that men had clubbed at each other with their guns. Telling which side the bodies had been on “was near impossible.” Those that could be separated told a story: “Our Patriot militia mostly wore a white paper (in his) hat which weren’t a good idea as it made a good target for the Tories. There was several boys shot straight in the head through their hats.”

Falls had been his captain in a battle in South Carolina. “I knelt down beside him and I just had to cry seeing him there like that.”[ii]

A Sharpe Shooter Downs an Officer

Walk back up the sidewalk to the parking lot. Continue up the gravel steps on the right to the monument to Tory Col. Nicholas Warlick at the summit. Note the sign warning visitors to stay off of school grounds when school is in session. You are free to explore the summit, but please do not pass the fences at those times.

The Patriots who have made their way around the ridgeline are slowly coming up the far hillside toward you, moving from tree to tree. There is a small stand of trees on the sharpest part of the slope below you, as there is today, and Whig riflemen have stationed themselves there. Loyalists are in a line between you and them, shooting downhill at random.

The Patriots who have made their way around the ridgeline are slowly coming up the far hillside toward you, moving from tree to tree. There is a small stand of trees on the sharpest part of the slope below you, as there is today, and Whig riflemen have stationed themselves there. Loyalists are in a line between you and them, shooting downhill at random.

Down there, probably, two riflemen friends are sharing a tree for cover as they fire. One is left-handed, and the other a rightie. But John Smith is shot in the chest, and before he dies cries out, “Robert, tell Polly I’m gone; fight on, Robert!”[6]

Two Whig brothers down there, named Sharpe, are skilled marksmen. They see Col. Warlick on horseback near this spot and discuss who will try to hit him. One brother states he is the better shot and should do it, but as he takes aim is hit by a musket ball in the arm. The other takes the shot, and Warlick falls dead. (Some sources claim this is the origin of the term “sharpshooter.” No Web resources on the word mention this incident, but the battle predates all but one of the other explanations, so it is possible.)

Warlick’s death convinces the Tories their position has become perilous. From all sides of this spot, men begin pulling back to your left. They retreat down the hill and the road you were on, which continues across today’s elementary school diagonally, downhill toward Ramsour’s Mill.

The Patriots hesitate to pursue, perhaps recalling what happened the previous time the Loyalists got behind this summit. When they do finally converge here, most of the survivors are gone.

Warlick is believed to be buried where he fell, joined by his brother Philip who also died here, and another Loyalist. Read the marker and monument if you wish, and then go to the brick-walled area to your left.

This is the mass grave of 56 men from both sides, buried in a long trench left to right. Lt. Patton said he did part of the work: “After the battle, a group of us dug a trench on the far side of the hill, and laid the bodies of the dead men all together in it… It was terrible work—the worst I ever done in my life.”[7]

Before leaving the summit, you may want to read the “Camps of the Race” section below.

A Long Ride to Widowhood

Walk back to the parking lot and visit the monuments if you wish, which include a millstone from Ramsour’s Mill. Drive or walk back to Battleground Road and turn right on Jeb Seagle Drive. Pause where it curves to the left, and look or walk up to the bricked-in rectangle built by 1877.

The Patriot line spread along the stream to your left, so fighting continued all along the hillside here. Two Whig captains, John Bowman and John Dobson, lie in the enclosure near where they fell.

The Patriot line spread along the stream to your left, so fighting continued all along the hillside here. Two Whig captains, John Bowman and John Dobson, lie in the enclosure near where they fell.

Bowman, at least, does not die alone. His wife Grace receives word that he is severely wounded. She wraps up her 11-month-old child, gets on a horse, and rides 40 miles straight from their home. They are at his side when he dies, shortly after they arrived. (Grace later married Brig. Gen. Charles McDowell, and is buried by him in Morganton. The little girl grew up and is in the same cemetery. Dobson’s daughter and her husband are interred here near him.)

Accusations and a Near Hanging

Continue along the curve left and then right to the replica cabin on your left (parking is available). Go to the cabin, which is not original to the site. Look to your left.

The edge of the field marks the approximate location of the road followed by Hardin’s men. They likely formed their line along a fence beside it to shoot at the right flank of the Tories, uphill behind you.

The edge of the field marks the approximate location of the road followed by Hardin’s men. They likely formed their line along a fence beside it to shoot at the right flank of the Tories, uphill behind you.

The farmhouse and outbuildings of the Christian Reinhardt family, which owns the ridge at the time, are probably along the inside curve of the modern street.[a] Reinhardt has a blacksmith shop, a store, an ordinary (food-serving tavern), and by 1771, a large, hickory log home, on a stone basement, with portholes for firing at Native American raiders. That year he married Elizabeth Warlick, sister of Patrick. The next year the house was used as the county courthouse. Moore and his officers took over the Rienhardt home as their headquarters.

Wallace Reinhardt says Christian built the house and outbuildings and then went back to Pennsylvania to get tools. Forced here with him on his return was an African man called Fasso who had worked in a tannery before. Reinhardt had a tannery near the creek.

After the battle some of the wounded are brought to the Rienhardt house, and Elizabeth helps nurse them, Wallace Rienhardt wrote. Whigs come in and grab Christian, accuse him of being a Tory, put a rope around his neck, and take him toward the woods planning to hang him. Riep steps in on Reinhardt’s behalf and an argument ensues. Locke supposedly arrives and tells the accusers that Reinhardt’s information about the Tories, passed through Riep, was “invaluable.”[8]

Read the battle marker near the cabin if you like, and then turn right and go the grave marker.

This is the grave of Martin “Crooked Nose” Shuford. He and a group of fellow Tories captured 17-year-old Isaac Wise south of Hickory in 1776. Wise had defied his Tory father to support the Revolution. The Tories wanted to string him up, but had no rope. Shuford rode off to get one. But his horse tripped and he was thrown off, breaking his nose. He still managed to get the rope, and Wise was hung. Shuford was mortally wounded in this battle and died two days later.

Confrontation at the Mill

Take the trail downhill into the woods. As you near the creek, walk up the ramp of earth rising to the right of the trail, which was the same road you were on before at the sidewalk.

The mill pond is off to your right, covering the modern athletic field (raised since then) and the land on that side across the creek. Hundreds of men are pouring down the hill at a sprint and pushing past you here. Their only goal now is to get over the bridge ahead of you over the creek. To avoid the traffic jam forming here, some of the Tories are swimming across the pond. At several places along the shore (at the edge of the athletic field), laggards are being shot and/or drowned by Patriots.

The mill pond is off to your right, covering the modern athletic field (raised since then) and the land on that side across the creek. Hundreds of men are pouring down the hill at a sprint and pushing past you here. Their only goal now is to get over the bridge ahead of you over the creek. To avoid the traffic jam forming here, some of the Tories are swimming across the pond. At several places along the shore (at the edge of the athletic field), laggards are being shot and/or drowned by Patriots.

When you get to the end of the ramp, look across the creek.

The stone wall you see is probably part of the mill foundation, extended to support the road at that point. The mill building is to your left. The water wheel is not in the creek, but in a dug-out channel (“millrace”) that arced past the far side. The mill was built here, where several Native American trails crossed, by Diedrich Ramsour, who had died in 1772. It now is run by his son Jacob.[9] The bridge is above or resting on the mill dam and foundation.

Riep lives in a cabin 1-1/2 miles to the northwest, according to a local historian. He says Fasso probably led Elizabeth Rienhardt, Riep’s wife Sarah, and the Rienhardt children to a hideout near the cabin when the battle broke out.[10]

Now roughly 400 Tories gather past the mill, possibly taking a line of defense along the creek to the left, as the Patriots finally come up behind you.

Someone hangs a white sheet of surrender in a window of the mill. The Patriots back off. After a time a small group of Tories carrying a flag of truce made from something in the mill appears. They come back across the bridge and go up the hill to parlay.

While that is happening, however, word gets to the Tories that a large force of militia under Col. Rutherford is arriving from the far side of the battlefield. You see most of the Tories melt away in the distance. When the flag party comes back, only about 50 of the Loyalists remain.

Rutherford had sent a courier telling Locke not to attack, but it arrives too late.[11] Rutherford’s forces show up around noon and scour the countryside capturing more Tories. Approximately 200 are marched off to a prisoner of war camp in Salisbury.

Wallace Rienhardt says buzzards circled the hill for weeks after the battle.[12]

Battle Map

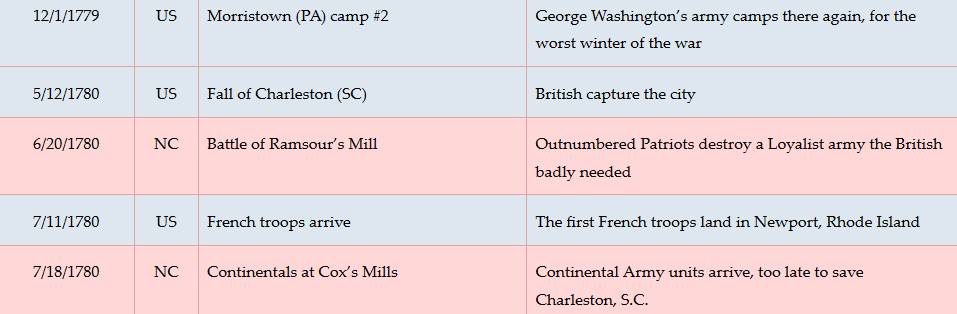

The Battle of Ramsour’s Mill: All locations are approximate. 1) After driving in Tory pickets, Patriot cavalry charge the camp. 2) Patriot infantry attack; battle spreads along the hillside. 3) More Whigs arrive and begin firing on the Tory right flank. 4) Patriot sharpshooters move around the hill, killing Col. Warlick (small red square). 5) Tories retreat across the creek and pond.

Camps of the Race

Seven months later, having handed a British force a stinging defeat at the Battle of Cowpens (S.C.) and captured 500 prisoners, one wing of the regular Continental Army is being chased by Cornwallis. This is the start of the “Race to the Dan.”

Seven months later, having handed a British force a stinging defeat at the Battle of Cowpens (S.C.) and captured 500 prisoners, one wing of the regular Continental Army is being chased by Cornwallis. This is the start of the “Race to the Dan.”

On Sunday, January 21, 1781, most of Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan’s Continental Army arrives and camps on the old battlefield. Morgan is hoping to get across the Catawba River and meet up with the main Continental Army, and has sent a detachment north already with the prisoners. After two nights they head toward the Catawba River fords, probably east along Sherrill’s Ford Road.

Two days after Morgan leaves, Cornwallis’ army arrives from Winnsboro, S.C., by way of the Tryon County Courthouse (northwest of modern Gastonia) and camps on both sides of Clarke’s Creek. Cornwallis orders his headquarters tent placed somewhere on the summit.[13]

After getting a tour of the battlefield from Reinhardt, Cornwallis supposedly remarks, “‘Moore had a good position, but did not know how to defend it.’” He notes that Moore made mistakes in letting the riflemen around his left flank, and not concentrating his forces behind the woods on the hillside.[14]

For three days the British forage the area for food, with Ramsour’s Mill running day and night to grind grain. One source says Cornwallis’ men find a supply of leather in the mill, allowing them to repair shoes and carry extra soles.[15] Cornwallis paid Rienhardt for the leather they took and cows they killed for food. He supposedly gave Fasso £2 ($400 today) and some tanning tools, which Fasso kept the rest of his life.[16]

Cornwallis then orders his troops to burn most of their own wagons, parked at the mill, except for those holding ammunition, medicine and salt, plus four empties for the sick or wounded. Some of the destroyed supplies are dumped in the mill pond.[17] Cornwallis knows Morgan to be encumbered with his own wagon train and (he thinks) the prisoners, so he hopes to move faster to catch up. His troops will have to carry the bare necessities.

The commander tries to set a good example: “Cornwallis first ordered his splendid camp chest burned. His mahogany tea chest with the remainder of his tea, and six solid silver spoons, he sent to Mrs. Barbara Reinhardt, wife of Christian Reinhardt, with a note requesting that she accept them.” Marking perhaps as great a loss, “Where the whiskey and rum bottles were broken the fragments lay in heaps for years.”[18] A British officer reported that as the rum was poured out, “‘The men looked on sadly, but passively.’”[19] No doubt the single most disturbing line in Cornwallis’ order for most of the men was, “‘The Supply of Rum for a time will be Absolutely impossible.’”[20]

On the morning of the 28th, the British follow in the Continentals’ bootsteps. Brig. Gen. Charles O’Hara later wrote about the decision: “‘In this situation, without baggage, necessaries, or provisions of any sort for officer or soldier, in the most barren inhospitable, unhealthy part of North America, opposed to the most savage, inveterate, perfidious, cruel enemy, with zeal and with bayonets only, it was resolved to follow Greene’s army to the end of the world.’”[21]

Casualties

After the Battle

- Moore and 30 others make it to Cornwallis in South Carolina. The general, furious Moore defied his orders to delay gathering forces, nearly court-martials him. A Patriot militia captain reports he was captured there a year later, tried and convicted as a spy, and hung.[22]

- Loyalist forces never re-form in this region. Had these 1,300 men been at the Battle of King’s Mountain (S.C.) four months later, that might have been a British victory, and in turn Cornwallis might have had the numbers necessary to win his 1781 campaign through North Carolina.

More Information

- Anderson, William, ‘Battle of Cowan’s Ford’ (EleHistory Research, 2018)

- Babits, Lawrence, and Joshua Howard, Long, Obstinate, and Bloody: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009)

- Barefoot, Daniel, Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1998)

- ‘Battle of Ramsour’s Mill’, American Revolutionary War, 2017 <https://revolutionarywar.us/year-1780/battle-ramsours-mill/> [accessed 15 December 2019]

- ‘Battle of Ramsour’s Mill: June 20, 1780 (Map Sketch)’, Archives, Lincoln County Historical Association

- Baxley, Charles, The Battle of Ramsour’s Mill: June 20, 1780, V. 2.2, 2018

- Fair, Victor, ‘The Hills of Home’, Lincoln County Public Library, North Carolina Collections

- Fair, Warren, The Battle of Ramsaur’s Mill (Lincolnton, N.C.: The Lincoln Times, 1937)

- Graham, William A. (William Alexander), General Joseph Graham and His Papers on North Carolina Revolutionary History (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton, 1904) <http://archive.org/details/cu31924032738233> [accessed 27 March 2020]

- Hartshorn, Derick, ‘Ramsour’s Mill Anniversary-2006’, NCGenWeb, 2008 <http://www.ncgenweb.us/lincoln/military/RamsoursMill.htm> [accessed 26 February 2020]

- Jones, Randell, Before They Were Heroes at King’s Mountain, North Carolina/Tennessee Edition (Winston-Salem, NC: Daniel Boone Footsteps, 2011)

- Lewis, J.D., ‘The Battle of Ramsour’s Mill’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2011 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_battle_of_Ramsours_mill.html> [accessed 16 December 2019]

- ‘Marker: O-3’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=O-3> [accessed 30 May 2020]

- Nixon, Alfred, The History of Lincoln County (Lincolnton, N.C.: Lincoln County Historical Association, Inc., 1983)

- Nixon, Alfred, ‘The History of Lincoln County, North Carolina’, The Lincoln County News (Lincolnton, NC, 1935) <http://archive.org/details/historyoflincoln00nixo> [accessed 16 June 2020]

- O’Kelley, Patrick, Nothing but Blood and Slaughter: The Revolutionary War in the Carolinas, Volume Three, 1781 (Booklocker.com, Inc., 2005)

- ‘Overlays of Fair/Reinhardt Map on Aerial Photographs: 1951H, 1968H, 1999, 1999H’, Archives, Lincoln County Historical Association

- Pancake, John S., This Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas, 1780-1782 (University, AL : University of Alabama Press, 1985) <http://archive.org/details/thisdestructivew00panc> [accessed 13 October 2020]

- Partridge, Dennis, ‘Route of the British Army through Lincoln County, North Carolina’, North Carolina Genealogy, 2016 <https://northcarolinagenealogy.org/lincoln/british_army_lincoln.htm> [accessed 25 December 2019]

- Patton, Chuck, ‘Reminisences from Ramsour’s Mill’, The Lincoln Sentinel, I.II (1999).

- Schenk, David, North Carolina 1780-1: History of the Invasion of the Carolinas (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton, 1889)

- Sherman, Wm. Thomas, Calendar and Record of the Revolutionary War in the South: 1780-1781, Tenth Edition (Seattle, WA: Gun Jones Publishing, 2007) <https://www.americanrevolution.org/calendar_south_10_ed_update_2017.pdf>

- Smith, Austin, ‘“Neighborhood in Constant Alarm”: The Battle of Ramsour’s Mill and Partisan Divisions in the Carolina Backcountry Communities during the American Revolution’ (Bachelor’s Honors Thesis, University of Arizona, 2010)

- ‘The German Settlers in Lincoln County and Western North Carolina’, The James Sprunt Historical Papers, II.2 (1912)

- Yianopoulos, Mike, ‘The Battle of Ramsour’s Mill Phased Battle Maps, V.2’, 2019

- Ward, Christopher, The War of the Revolution (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1952), Vol. Two

[1] Smith 2010.

[2] Graham 1904.

[3] Marker O-3 essay.

[4] Fair, V.

[5] Patton 1999.

[6] Barkley, John, Letter to Lyman Draper, 1/19/1887, quoted in Cathey, Boyt Henderson, Cathey Family History and Genealogy, Vol. 1 (1700-1900) (Franklin, N.C.: Genealogy Publishing Service, 1993). The author was the grandson of Robert (Barkley), and says he had seen the bullet that killed Smith.

[7] Patton.

[8] Nixon 1935.

[9] “The German Settlers in Lincoln County…”

[10] Fair, V.

[11] Jones 2011.

[12] Fair, V.

[13] Jones 2011.

[14] Nixon 1983.

[15] O’Kelley 2005.

[16] Nixon 1983; $400: Eric W. Nye, Pounds Sterling to Dollars: Historical Conversion of Currency, accessed Saturday, June 04, 2022, https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm.

[17] Wagons at mill, supplies dumped: Nixon 1983.

[18] Jones 2011.

[19] Ward 1952.

[20] Joshua and Howard 2009.

[21] Charles O’Hara to Duke of Grafton, 4/20/1781, quoted in Sherman 2007.

[22] Graves 1780.

[a] “Overlays of Fair/Reinhardt Map on Aerial Photographs: 1951H, 1968H, 1999, 1999H.”