A Poignant Patriot Moment

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.6674, -80.4699.

Type: Sight

Tour: Race to the Dan

County: Rowan

Park anywhere near the intersection of Main Street and Innes Street at the coordinates, where our tour starts.

Our route uses sidewalks plus some drives, or can be entirely driven, though parking opportunities are limited in some places.

Context

After defeating Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens (S.C.), a Continental Army corps under Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan marched rapidly north, escaped the trailing British army at the Catawba River, and then raced to get to the Yadkin River safely.

After defeating Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens (S.C.), a Continental Army corps under Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan marched rapidly north, escaped the trailing British army at the Catawba River, and then raced to get to the Yadkin River safely.

Situation

British/Tory

The British army under Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis was delayed at Cowan’s Ford across the Catawba (now the base of Lake Norman), and at Torrence’s Tavern on the Salisbury-Charlotte Road east of there. Next it tried but failed to catch the Americans at the crossroads that today is Mooresville, west of Salisbury. It fell into their footprints in hopes of trapping the Americans against the river.

Continental/Patriot

Morgan’s corps raced along the route followed now by NC 150 and into Salisbury, while Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene rode by himself up the Salisbury-Charlotte Road after conferring with the rear-guard leaders. The overall commander of the Continental Army in the South, he had hoped the British would be blocked at the Catawba long enough for his main army to arrive here to fight Cornwallis. He waited into the early morning hours at a rallying point seven miles north of Torrence’s until a messenger arrived, informing him the British had crossed the Catawba.

Salisbury

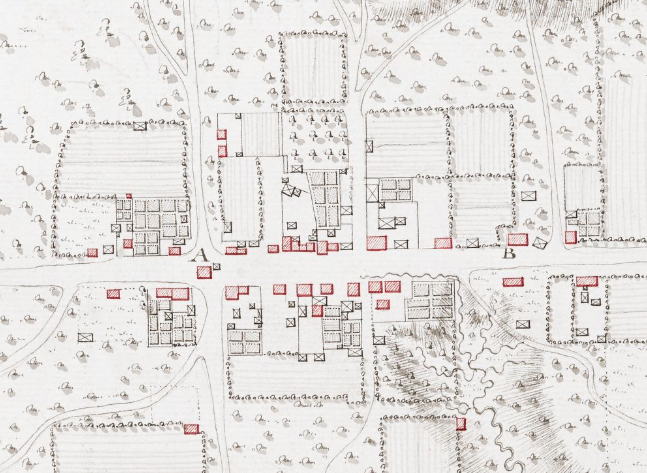

Salisbury was founded in 1753 to provide Rowan County a courthouse and jail, on a Native American trading path (now Innes Street) just uphill of its intersection with a second, likely where the railroad is today.[1] Salisbury is a “major supply and manufacturing center for the southern Continental army,” from which the rebels “would need to evacuate the small garrison and many prisoners of war, as well as the artisans who worked in the military manufacturies located in the town.”[2]

Dates

Monday, August 8, 1774–Monday, February 5, 1781.

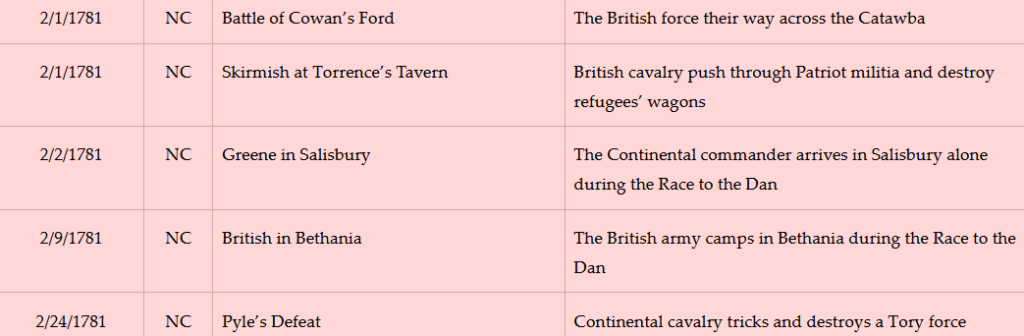

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

An Early Call for Resistance

Walk to the intersection of Main Street and Innes Street.

During the American Revolution, the courthouse is in the intersection, a typical practice of the day (like in Charlotte and Wilmington). Assuming the 1755 building fits the plans called for by the county court—which was also the county government—it is a wooden building “thirty feet long and twenty wide, a story and a half high, with two floors, the lower one raised two feet above the ground.” Inside is “an oval bar (meaning “rail”) and a bench raised three feet from the floor” opposite the door, with “a good window behind the bench, with glass in it, and a window near the middle of each side…” The building is in poor condition, but the court cannot raise enough money to fix it.[a]

During the American Revolution, the courthouse is in the intersection, a typical practice of the day (like in Charlotte and Wilmington). Assuming the 1755 building fits the plans called for by the county court—which was also the county government—it is a wooden building “thirty feet long and twenty wide, a story and a half high, with two floors, the lower one raised two feet above the ground.” Inside is “an oval bar (meaning “rail”) and a bench raised three feet from the floor” opposite the door, with “a good window behind the bench, with glass in it, and a window near the middle of each side…” The building is in poor condition, but the court cannot raise enough money to fix it.[a]

Though no records from the time confirm this, the courthouse is likely where the Rowan County Committee of Safety meets on Monday, August 8, 1774. In response to an invitation to a colony-wide meeting from the Wilmington committee, this group of landowners is one of many in the Province of North Carolina formed to support Boston. That city had been targeted by the British Parliament with laws to punish it for rebellious acts including the Boston Tea Party.

The committee adopts what it titles, “Resolutions by inhabitants of Rowan County concerning resistance to Parliamentary taxation and the Provincial Congress of North Carolina,” now called the “Rowan Resolves.” While they profess loyalty to King George III, the men also insist that only the Provincial Assembly (legislature) has the right to tax them, as had been the practice in America until the 1760s. They descry the use of the British military against citizens in Massachusetts; support a boycott of English goods and imports of enslaved people (for economic reasons, not abolition); encourage domestic manufacturing and farming; appoint delegates to the planned colony-wide convention; and support the planned Continental Congress. They add, “it is the Duty and Interest of all the American Colonies, firmly to unite in an indissoluble Union and Association to oppose by every Just and proper means the Infringement of their common Rights and Privileges.”[3]

Among the signers are later Revolutionary War Patriot leaders Matthew Locke and William Davidson, and possibly Charles McDowell.[4] This is the first such declaration in North Carolina; though the title and some of the language is modeled on the Wilmington letter, Rowan’s is more radical in its complaints.

Many details about Revolutionary Salisbury come from a single source. An 1850 Davidson College graduate, school teacher, and preacher, Jethro Rumple, wrote a series of newspaper columns collected into a book for the centennial of the war in 1881. He consulted primary documents like memoirs, but admits his stories are mostly from oral histories. The quoted dialogs on this page are from him unless otherwise noted, and appear to be embellished for dramatic effect. Believe with caution!

Check the street signs and look down South Main Street.

More than six years later, Morgan’s Continental and militia soldiers begin to appear from the south on the afternoon of Friday, February 2, 1781. Nearly 800 men, wagons, and 500 British or Loyalist prisoners drag past you. They camp about a half-mile east of town (visited below). Greene had hoped the rest of his army would arrive from its camp in South Carolina in time to confront Cornwallis, but instead is forced to move across the river at the Trading Ford seven miles northeast.

The next day, Cornwallis’ army marches up this same street, arriving around 3 p.m. They continue past you through town, hoping to catch the Continentals. The cavalry and fast-moving (“light”) infantry corps go to the ford, while the rest camp four miles east of town after a 20-mile march this day. (Visit the Trading Ford to learn what happens next.)

Greene Makes a Lasting Statement

Walk up North Main Street on the northwest (left) side. As you near the end of the block, look down at the sidewalk near the street until you see the historical plaque for Elizabeth Steel. Face the nearest building.

An “ordinary,” a tavern with overnight rooms that serves food, stands from around here to the next street. In the mid-1760s, western landowners began complaining to the colonial government about corrupt county officials, unfair taxes, and other problems. Nothing was done by the royal governor and legislature, and by 1770 violence had broken out in Hillsborough. On Thursday, March 7, 1771, a group of these “Regulators,” including famous spokesman Herman Husband, meet here at the tavern with local officials. Among those are two who will play roles in the coming Revolutionary War: Francis Locke (brother of Matthew) and Griffith Rutherford. Unlike peers further east, these men agree to pay back any money “over and above what we… ought to have taken for fees, more than the law allowed or entitled us to receive…”[b]

An “ordinary,” a tavern with overnight rooms that serves food, stands from around here to the next street. In the mid-1760s, western landowners began complaining to the colonial government about corrupt county officials, unfair taxes, and other problems. Nothing was done by the royal governor and legislature, and by 1770 violence had broken out in Hillsborough. On Thursday, March 7, 1771, a group of these “Regulators,” including famous spokesman Herman Husband, meet here at the tavern with local officials. Among those are two who will play roles in the coming Revolutionary War: Francis Locke (brother of Matthew) and Griffith Rutherford. Unlike peers further east, these men agree to pay back any money “over and above what we… ought to have taken for fees, more than the law allowed or entitled us to receive…”[b]

After her second husband died in 1774, Elizabeth Maxwell Steel took over running the tavern and also successfully speculated in real estate. (Her first husband was scalped by Cherokees in 1760, during the French & Indian War.)

Dr. William Read, head of the medical service for Greene’s army, is in the tavern doing paperwork after Morgan passed through town. You may see Rumple’s embellished version of this story elsewhere, but based on Read’s account from an early biography of Greene[5], Read sees Greene arrive late that evening. “‘What alone, General?’” he asks.

“‘Yes,’” replies Greene, “‘tired, hungry, alone, and penniless.’” He has been riding for five days, at least 130 miles, from the main army camp on the Pee Dee River (lower Yadkin) in S.C., to camps on the Catawba (now under Lake Norman), to here. The last day’s ride was made alone, in fear of getting caught by British cavalry, and in fact they were within four miles of him at Torrence’s Tavern.

Steel overhears him, and invites him to a table. She brings him dry clothes and lays out dinner as Greene warms up. After he has eaten, she enters the room and holds out both hands, each with a bag of coins in it. She says, “‘Take these, for you need them, and I can do without them.’” The money is believed to have been used to purchase supplies for the army later in the campaign.

Before leaving, Greene spots prints of King George and Queen Charlotte on the wall, presents sent from London to Steel by her sister long before the war. Greene takes George’s down, and scrawls on the back in chalk, “O George! hide thy face and mourn.” He puts it back, face to the wall. The paintings and his words still exist, at Thyatira Presbyterian Church west of town.

As you can see on the marker, Steel later writes a relative that “the British were so kind as to pay us a visit” and she lost “all of my horses, my cattle, horse forage, liquors, and family provisions…”

A Place for Prisoners

Continue on Main, cross the next street, and walk one block to the corner with Liberty Street.

The modern street name is ironic, because sometime before 1770 the county jail was built here. It stretches across the current road, which did not exist at the time, along Main. In addition to common criminals, Loyalist prisoners are held here at times, guarded by militia soldiers.[c] A log cabin is about a third of the way up the current block and offset to the right, but slightly overlapping with the jail’s footprint. This chance arrangement comes in handy.

The modern street name is ironic, because sometime before 1770 the county jail was built here. It stretches across the current road, which did not exist at the time, along Main. In addition to common criminals, Loyalist prisoners are held here at times, guarded by militia soldiers.[c] A log cabin is about a third of the way up the current block and offset to the right, but slightly overlapping with the jail’s footprint. This chance arrangement comes in handy.

In December 1780, Greene sends a detailed letter ordering the construction of a prisoner-of-war camp behind the jail. He requires it to be a half-acre in size, and goes into specifics of construction starting with the “pickets,” meaning the logs making up the stockade wall:

“‘One half of the pickets should be cut eighteen feet long, and the other fifteen feet, and be about eight inches thick. They should be placed three or four feet in the ground, and close to each other, and secured by trunneling ribs on the outside, about half way up the pickets. The upper ends should be made sharp; they should be placed in such a manner that every one of the short ones will make a loop-hole through which the sentries might watch or fire upon the prisoners. The sentries should have a scaffold to walk on, on the outside, at a proper height to enable them to see the whole of the prisoners at one view. The prisoners will be able to erect huts within the pickets for them to cook and sleep in.’”[6]

The jail is the only entrance, which suggests the stockade is behind the jail; the log cabin inside it; and an extension built off the back door of the jail to connect to the stockade. A lack of tools and labor prevent the stockade from being fully completed, though some prisoners are held here for a time.[d] As the British approach, Greene orders them taken to Virginia.[7]

Cornwallis’ Camp

Turn left, and walk one block “through” the edge of the jail and POW camp. Cross Church Street. Turn left and go to the Old English Cemetery entrance on the right. Face it or go in.

Cornwallis continues to the ford on Sunday, but fails again to catch Morgan. He also finds the river too flooded to cross, and that the Continentals have secured all the boats in the region on their side. He is forced to bring his army back to town to wait it out.

Cornwallis continues to the ford on Sunday, but fails again to catch Morgan. He also finds the river too flooded to cross, and that the Continentals have secured all the boats in the region on their side. He is forced to bring his army back to town to wait it out.

This cemetery exists in 1781, used by English settlers, not Germans and others. The name becomes very appropriate: The British camp stretches from perhaps a block to the right to at least a couple blocks left, past Innes, between Main and Fulton (the back side of the block you are on). Sources differ on the exact location, and underestimate how large Cornwallis’ camps were—more than two miles in a similar linear arrangement a couple weeks later. The Redcoats likely covered at least the western half of the modern downtown, extending out of sight to your right and left. They do not have tents, having burned most of their wagons at Ramsour’s Mill (in today’s Lincolnton) to move faster, so men settle in next to hundreds of campfires.

The British bury an unknown number of men who died on the trip somewhere here in the cemetery. American veterans later are buried here as well.

Continue south (the direction you were walking) on Church Street, across Council Street, and stop at the rear of St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. Face the church building.

The law office of John Dunn stands at the corner, and is occupied by the British commissary (supply) officers. His daughter, Eleanor Faust, has a home in the back yard, its site now covered by the sanctuary. Rumple says a commissary officer knocks on the door and asks to buy a favorite calf from Faust to serve to Cornwallis. She refuses. An officer orders his men to take it anyway, and “laid down a piece of gold before Mrs. Faust as pay. Irritated and indignant, she pushed away the money, and left his presence.”

Walk to the corner and turn right. Go partway up the block until you are near the driveway leading into the church parking lot.

For a moment, step forward in time one year. Both regular armies have left the state, and the Revolution in N.C. now is strictly a civil war between Patriots and supporters of the king called “Loyalists” or “Tories.” The most infamous of Tory leaders is Col. David Fanning, whose exploits include murders and the kidnapping of the state governor and other leaders.

According to Rumple, an Englishman named Joseph Hughes has an inn here in March 1782. Word comes that Fanning is headed this way over the Trading Ford. Though Hughes only had one arm, “he rolled some barrels of whiskey into the street in front of his inn, knocked the heads out, and placed a number of tin cups conveniently around. The bait took, and Fanning’s (followers) got beastly drunk, and so were disabled from doing the mischief they intended to do. Hughes seized the opportunity to escape through the thickets and brushwood in the rear of his house.”

Look further out Innes Street.

Back in 1781, though the river is dropping the next day, Cornwallis determines he cannot delay the chase. Giving up on the Trading Ford, the British march out Innes Street, then the road to Mulberry Fields (today’s Wilkesboro). They are headed for narrower Shallow Ford upriver, more than 30 miles north of town.

Go back to Church Street. Turn right, and continue down it across Fisher Street. Pause just past that and read the marker about the Macay Law Office.

N.C militia leader William Davie studied law here during the war, after being badly wounded at the 1779 Battle of Stono Ferry (S.C.). He returned to military service the next year after Charleston fell to the British.

Later President Andrew Jackson, wounded as a boy while defending his mother from a British officer, studied here after the war. Asked as president about his time in the village, Jackson replied, “‘Yes, I lived at old Salisbury. I was a raw lad then, but I did my best.’” That quote is from a 1953 county bicentennial program that adds, “contemporaries described him as being the most rollicking, horse-racing, dueling, lawless citizen in town.”[8]

Walk a little further to the old well.

This later-era structure covers a well used by the British soldiers for water.

Go on to Bank Street and cross it to the marker on the far corner.

Cornwallis has taken over the home of Maxwell Chambers, a merchant and Patriot, who made himself scarce. Soldiers stand guard, while others regularly go in and out carrying messages and orders.

Turn left, and walk down Bank a block to Main Street. Turn left on Main and walk back toward Innes.

Somewhere along the other side of Main, Rumple says, Dr. Anthony Newnan’s family has been forced to house some officers. They have been joined for dinner by Tarleton, the British officer Morgan defeated at the Cowpens, who was chased off the field by Lt. Col. William Washington (a distant cousin of George). They briefly fought each other with swords.

Newnan’s two young boys are “playing a game with white and red grains of corn.” A couple games of the day use these, but this night the boys decide to make the grains Americans and Redcoats and recreate the Battle of Cowpens. Rumple says one of the boys forgetfully yells, “‘Hurrah for Washington! Tarleton is running! Hurrah for Washington!’” Tarleton tries to contain his anger but then curses at the boy.

Morgan’s Camp

If walking, go back to your car. Drive six blocks north on Main Street from Innes Street (in the direction you first walked), to Franklin Street on the right. Turn right, and park immediately. Look over your left shoulder to the far side of Main Street.

On the left side of Main just past the modern line of Franklin stands, in 1781, the James Beard home. James, a Patriot, has taken off. Mrs. Beard (no first name given) has been forced to host Tarleton, who makes himself at home. Rumple says, “When he wanted milk he ordered old Dick—the (enslaved) servant—to fetch the cows and milk them.” But his arrogance is repaid. “Mrs. Beard had a cross child at the time, whose crying was a great annoyance to the dashing colonel.”

On the left side of Main just past the modern line of Franklin stands, in 1781, the James Beard home. James, a Patriot, has taken off. Mrs. Beard (no first name given) has been forced to host Tarleton, who makes himself at home. Rumple says, “When he wanted milk he ordered old Dick—the (enslaved) servant—to fetch the cows and milk them.” But his arrogance is repaid. “Mrs. Beard had a cross child at the time, whose crying was a great annoyance to the dashing colonel.”

Continue to the end of the block and:

- Turn left on Lee Street.

- Cross the tracks, and turn right on Railroad Avenue.

- Where the road curves left, pause or park where you can see the commercial buildings across the railroad on the right.

Morgan’s corps probably camps in this area, near the route to the Trading Ford (current Main Street), the night it arrived in town, Friday, February 2.[9]

Daniel Morgan is in so much pain from sciatica and arthritis, he has been making the trip in a wagon. The problem would soon force him out of the service, but he has done his part for independence.

Old Stone House

A couple of Rumple’s stories are associated with the Old Stone House outside of town. Take note of the first “Historical Tidbit” below, and then:

- At the end of the curve, turn right onto Henderson Street.

- Drive across the tracks, and turn right on Long Street.

Note: Per the tidbit, you probably just crossed the trading path followed by Lawson. - Drive seven blocks and get in the left turn lane at Innes Street.

- Turn left, and drive 4.0 miles (as Innes becomes US 52) into the town of Granite Quarry.

- Just before the “Old Stone House” state historical marker on the left, turn left on East Lyerly Street.

- Drive 0.5 mi. to the house on the right.

Walk to the near, front, door.

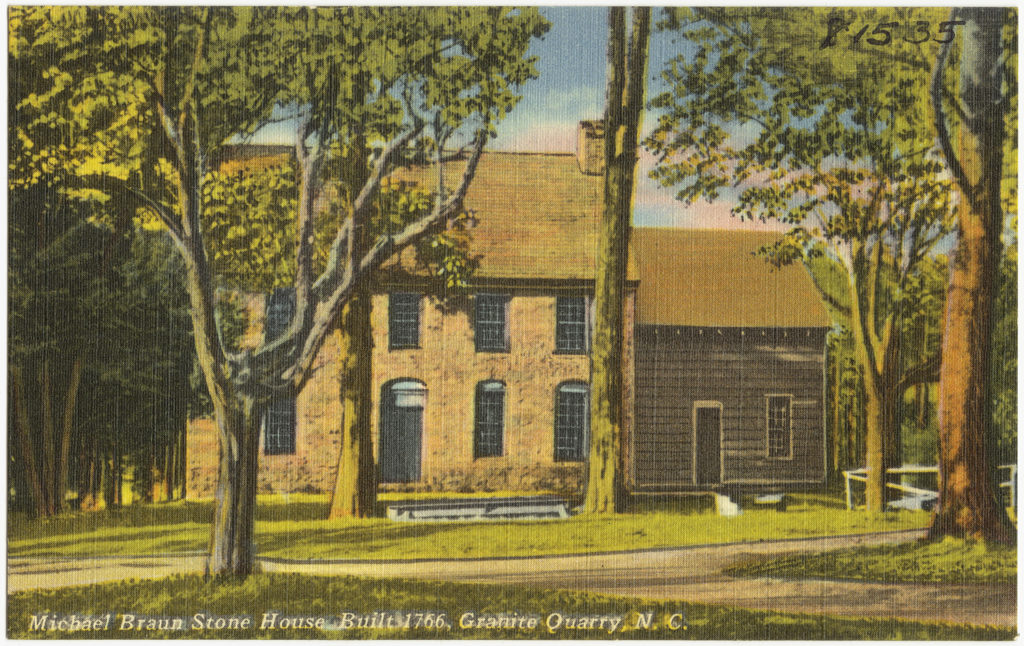

Old Stone House was built by Michael Braun, a German immigrant. He arrived in Philadelphia in 1737, spent 20 years there learning construction and other trades, and then bought land both here and in later Salisbury.

Old Stone House was built by Michael Braun, a German immigrant. He arrived in Philadelphia in 1737, spent 20 years there learning construction and other trades, and then bought land both here and in later Salisbury.

Look at the inscription to the right above the door. According to the essay written for the state historical marker, “it is inscribed with the names of Michael Braun and his wife and the lettering, ‘10-Pe-Me-Be-Mi-Ch-Da-1766.’ This appears to be an abbreviation of the German phrase, ‘Pensum Meines Bendigem Mit Christim Dank’ meaning ‘My undertaking completed thanks to God.’ The 10 and 1766 refer to the date of completion, October 1766.”[10] The oldest standing house in the western part of the state, it was occupied by Braun descendants until 1911.

Braun owned an inn, tan yard, and rental houses. He also served as a constable, roads supervisor, and justice of the county court (the local government in those days). There’s no record of what he did, or which side he was on, if either, during the Revolution.

Some of Tarleton’s heavy cavalry called “dragoons” are said to have gone past the house while chasing Morgan’s army on Saturday, February 3, 1781. Rumple reports:

- One story held that “an American officer, who was probably on a reconnoitering expedition, was nearly overtaken by British dragoons near this house. He turned and fled for life. As the party came thundering down the hill the American rode full tilt into the front door of this house, leaped his horse from the back door, and so escaped down the branch bottom and through the thickets, towards Salisbury.”

- Another “tells of a furious hand-to-hand encounter between an American and a British soldier in the front door of the stone house. The deep gashes of the swords (were) still shown in the old walnut doorposts” in Rumple’s day, but those had to be replaced. A different source says the British were using the house as a prison and the American was trying to escape, but this seems unlikely given how far it was from the British camp.[11]

Historical Tidbits

- In 1701, Englishman John Lawson, making an epic exploration of the Carolina colony mostly on foot in an arc from Charleston to Washington, N.C., walked up the Native American trading path along today’s railroad.[12]

- As president, George Washington stayed in Salisbury overnight on his tour of the southern states on May 30-31, 1791. The 1953 program quoted earlier says, “Barrels of tar were lighted, cannons boomed, hundreds of people gathered, speeches were made, parties were given and toasts were drunk to the great general.”[13]

More Information

- Babits, Lawrence, and Joshua Howard, Long, Obstinate, and Bloody: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009)

- Barefoot, Daniel, Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1998)

- ‘Built to Stand: Old Stone House’, Our State Magazine, 2010 <https://www.ourstate.com/old-stone-house-rowan-county/> [accessed 5 February 2020]

- Draper, Lyman Copeland, King’s Mountain and Its Heroes: History of the Battle of King’s Mountain, October 7th, 1780, and the Events Which Led to It (Cincinnati: Peter G. Thomson, Publisher, 1881) <http://archive.org/details/cu31924032752846> [accessed 31 March 2020]

- Dunaway, Stewart, Colson’s Ferry, Mill, Ordinary, Fort: A Revolutionary War Overview, Issue E, 2010

- Ervin, Samuel, ‘A Colonial History of Rowan County’, The James Sprunt Historical Papers, 16.1 (1917)

- Gerber, Mary, tran., ‘Pension Application of Amos Church, S8191’, Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters, 1833 <http://revwarapps.org/s8191.pdf> [accessed 27 May 2023]

- Graham, William A. (William Alexander), General Joseph Graham and His Papers on North Carolina Revolutionary History (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton, 1904) <http://archive.org/details/cu31924032738233> [accessed 27 March 2020]

- Greene, George Washington, The Life of Nathanael Greene: Major-General in the Army of the Revolution (G. P. Putnam and Son, 1871)

- Lewis, J. D., ‘A History of Salisbury, North Carolina’, 2019 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Towns/Salisbury_NC.html> [accessed 8 February 2020]

- Linn, Jo White, ‘Braun (or Brown), Michael’, NCpedia, 1979 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/braun-or-brown-michael> [accessed 14 December 2020]

- ‘Marker: L-71’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=L-71> [accessed 8 February 2020]

- ‘Marker: L-79’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=L-79> [accessed 8 February 2020]

- Pancake, John S., This Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas, 1780-1782 (University, AL : University of Alabama Press, 1985) <http://archive.org/details/thisdestructivew00panc> [accessed 13 October 2020]

- Rowan 200: Bicentennial, Rowan County, North Carolina, Souvenir Program, 1953

- Rumple, Jethro, A History of Rowan County, North Carolina (Salisbury, N.C. : Republished by the Elizabeth Maxwell Steele Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution, 1916) <http://archive.org/details/historyofrowanco00rump> [accessed 5 February 2020]

- West, William, ‘Steel, Elizabeth Maxwell’, NCpedia, 1994 <https://dev.ncpedia.org/biography/steel-elizabeth> [accessed 13 November 2020]

- Witt, Gretchen, Rowan Public Library, In-person interview and e-mail, 11/5/2020

[1] Lewis 2019.

[2] Babits and Howard 2009.

[3] ‘Resolutions by Inhabitants of Rowan County Concerning Resistance to Parliamentary Taxation and the Provincial Congress of North Carolina’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1774 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr09-0293> [accessed 17 December 2020].

[4] A man by a nearly identical name signed, minus the second “l” in the last name. Spelling, even of names by the named person, tended to be loose in those days. McDowell’s property in Quaker Meadows, now Morganton, was in Rowan County at the time.

[5] Greene 1871; a modern historian who read Gen. Greene’s letters says his grandson was “scrupulous” in portraying them accurately (Pancake 1985). So this dialog is likely more accurate than Rumple’s.

[6] Greene 1871.

[7] Dunaway 2010.

[8] Rowan 1953.

[9] Rumple said the camp was where a home owned by Judge John Henderson stood in his day, likely one shown on maps of that time diagonally across the modern tracks (Witt 2020).

[10] Marker L-79.

[11] Barefoot 1998.

[12] ‘Interactive Map’, The Lawson Trek <https://www.lawsontrek.com/interactive-map.html> [accessed 5 January 2021].

[13] Rowan.

[a] Ervin 1917.

[b] ‘Agreement Between Rowan County Public Officials and the Regulators Concerning Fees for Public Officials, Volume 08, Pages 521-522’, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1771 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr08-0191> [accessed 9 February 2022].

[c] ‘1778 & 1779 Guards at the Salisbury District Gaol’, North Carolina State Archives, Military Collection, Troop Returns, Rowan County.

[d] See for example Gerber 1833.