Patriots, “Pirates,” and Portraits

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.6504, -80.6369.

Type: Stop

Tour: Race to the Dan

County: Rowan

Pause in front of Thyatira Presbyterian Church at the coordinates to read about the congregation and its museum in the next section. (The church driveway goes straight off White Road where White curves right, coming from NC 150.) Then follow the directions to the cemetery behind it.

Seeing the graves on this page requires traversing typical Piedmont cemetery ground. The church requests that you visit during daylight hours only.

Its museum holds two unique artifacts from the war, but can only be visited on special days or by appointment.

Description

Church Building

Look at the sanctuary.

Founded no later than 1750, Thyatira Church calls itself North Carolina’s “Mother of Presbyterianism” for spawning a number of other congregations. It is the oldest legally documented congregation of any type in the west half of the state. The site of the Revolutionary-era building is visited below. The current one was erected in 1860, is noted for its brickwork, and features some original pews and an upper gallery built for enslaved people.

Founded no later than 1750, Thyatira Church calls itself North Carolina’s “Mother of Presbyterianism” for spawning a number of other congregations. It is the oldest legally documented congregation of any type in the west half of the state. The site of the Revolutionary-era building is visited below. The current one was erected in 1860, is noted for its brickwork, and features some original pews and an upper gallery built for enslaved people.

Museum

Look at the small separate building with a gate, to the left of the sanctuary.

As mentioned under “Location,” the Thyatira Heritage Museum is only open during special events or by appointment. Among items of church and local history are colonial prints of King George III and his wife Queen Charlotte.

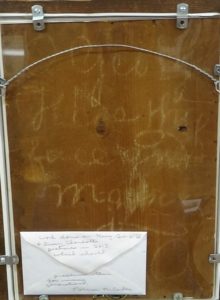

These hung on the wall of Elizabeth Maxwell Steel’s tavern. The Salisbury page details how Steel hosted Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, commander of the American army in the South. After defeating a wing of the British army at the Battle of Cowpens (S.C.), his subordinate Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan began transporting 600 prisoners north. The British gave chase, starting what now is called the “Race to the Dan.” Greene came to consult with Morgan, later escaping alone to Salisbury. After dining with Steel, he scrawled on the back of the king’s portrait in chalk, “O George, Hide thy face and mourn!” He then turned it toward the wall.

The words are still visible. As you can see in the photo, the “O G…” appears twice! The version in the lower right corner is upside down. He apparently started writing it, realized he was doing so the wrong way, rotated it, and tried again.

These portraits are extremely well traveled. Printed in England and sent to Steel by her sister, years after her death they ended up in the hands of David Swain. He became the state governor, so they are said to have hung in the Executive Mansion in Raleigh. Then he was the president of the University of North Carolina, so it presumably was at the Chapel Hill campus.[1] A man bought them at the auction of Swain’s estate in 1883 for 17 cents.[2] He took them to California when he moved there, and they ended up in a Palm Springs gallery in 1977. A descendant purchased them for the church.

Lockes as Leaders

Walk or drive to the right of the sanctuary into the cemetery. Go straight back until the driveway loops right, and park.

A few feet off the outside of the loop, spot the small square row markers in the ground. Continue to the right to “3E.” Walk along that row about halfway back, to the large monument in an otherwise empty portion of the cemetery.

During the Revolution, the congregation met in a wood-frame building here, the second sanctuary. The first was on the rise above the cemetery. Burials began when the church did, though the oldest visible tombstone dates to 1755. A number of veterans of the Revolution lie in this cemetery, among the 38 members who served, including a couple featured on other AmRevNC pages.

During the Revolution, the congregation met in a wood-frame building here, the second sanctuary. The first was on the rise above the cemetery. Burials began when the church did, though the oldest visible tombstone dates to 1755. A number of veterans of the Revolution lie in this cemetery, among the 38 members who served, including a couple featured on other AmRevNC pages.

Continue to the first grave in the row that has a “Patriot” marker in the ground in front of it.

This small tombstone marks the resting place of Col. Francis Locke. Locke, born in Northern Ireland, immigrated to Pennsylvania with his family as a child, and to the Salisbury area with his mother and step-father as an adult. He and his brother Matthew started what today would be a trucking company, running wagons between Charleston and Salem (now Winston-Salem) and also trading in skins for leather. Francis was a member of the local militia (part-time defense force) as early as 1759, and went with Brig. Gen. Griffith Rutherford on the 1776 Cherokee Campaign.

Locke also served in South Carolina and Georgia, but gained fame leading the Patriot militia victory over a much-larger Loyalist force at the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill. His mounted militia shadowed British forces in two invasions of North Carolina, inserting itself between the two British wings during the second one in Autumn 1780. He may have sat out the first part of the Race to the Dan at home, losing face with at least one militia officer.[3] However, after the British were blocked from crossing at the Trading Ford near Salisbury, Locke and his 100-man company burned a bridge on the route to the next suitable ford with only one casualty, despite nearly getting surrounded.

Locke was ordered to defend the western region of the state, and thus did not participate in later actions of the Guilford Battle campaign. But he remained in the militia until 1784.

You can learn about his civilian life at his homesite, visited later. Look at the monument to the right.

Francis’ son and namesake was a lieutenant in the militia during the war, probably serving in the same campaigns as his father, and later was a court justice and U.S. Congressman.

Continue down the row about 10 graves, to the next large marker.

Francis’ brother Matthew Locke bought 200 acres along the Charlotte-Salisbury Road the year the family moved to this area, 1752. In 1771 he was asked to help negotiate peace with the Regulators in Rowan County, people protesting unfair taxes and fees, among other concerns. His commission’s success—due in part to its paying off excess county fees—led to his election later that year to the Provincial Assembly. As “committees of safety” formed to fill in for the collapsing royal government, Locke was named to Rowan’s committee. He served in the rebellious provincial congresses in Hillsborough and Halifax in 1775-6, helping draft the Halifax Resolves and first state constitution. He was also a paymaster and commissary officer for the state militia, and may have held the rank of colonel in that role.[4]

Locke’s only combat service appears to be when he joined his brother on the Cherokee campaign. He was appointed temporary brigadier general and commander of the multi-county district militia in 1778, but saw no action.

An 1828 author says Greene’s chief medical officer, Dr. William Read, told him a story that reflects something of Locke’s character. During the Race to the Dan, Greene sent Read to Locke’s house for militia troops to help escort the prisoners. There Read was informed that the general was “‘at plough in his field.’” A passerby pointed out the path. Shortly he came across an “old man” with a “sorry” farm horse plowing. Read asked, “‘tell me, friend, where I can find General Lock (sic)?’”

“‘Come with me… and I will carry you to him.’”

The man led him back to the house. Irritated, Read demanded, “‘but where is the General?’

“‘You shall see him immediately,’” the man said, disappearing into another room. He quickly returned in full uniform “and large cocked hat.” He exclaimed, ‘I am General Lock—your business is with me, friend.’” The “old man”—Locke would have been around 51—gathered the troops and had them where needed the next day, Read said.[a]

When the war was over, Locke was elected to both houses of the state assembly and the state conventions considering the U.S. Constitution. He voted against it twice, in part because he felt it did not provide enough protection for personal rights. In the assembly he argued to drop the requirement of property ownership for voting nearly a hundred years before that was adopted, and for all (Christian) ministers to be allowed to marry people, instead of just those of an official church. Elected to Congress in 1793, he was a strong supporter of Nathaniel Macon, the nationally famous U.S. Speaker of the House from North Carolina. Locke died eight years later around age 71.

The George Lock who lies two graves to the right is not Patriot militia Lt. George Locke, killed during the Battle of Charlotte. A four-year-old is here, buried in 1776.[b]

Crossbones and Steel

From little George’s grave, turn around, and walk straight two rows. Face the front side of the small gravestones there and to the right.

The four headstones with skull-and-crossbones markings are called the “Pirate’s Graves.” Who is buried here, when, and why the markings exist, are unknown. The most likely reason, based on a practice in England, is that they died of a highly contagious disease, and the markings are a warning to graverobbers not to dig up the bodies.[5]

The four headstones with skull-and-crossbones markings are called the “Pirate’s Graves.” Who is buried here, when, and why the markings exist, are unknown. The most likely reason, based on a practice in England, is that they died of a highly contagious disease, and the markings are a warning to graverobbers not to dig up the bodies.[5]

Look behind the “pirates” toward the far (west) wall of the cemetery. Toward the right in the distance, spot the obelisk that looks like the Washington Monument. Go to it.

Elizabeth Steel, mentioned above and buried here, fed Greene and gave him two bags of money to resupply the Continental Army (detailed on the Salisbury page). She was also Rev. Samuel McCorkle’s mother-in-law.

Walk to the right past two regular tombstones to the “table marker,” which looks like a tomb. The body is actually buried at a normal depth in the ground below.

Rev. Samuel McCorkle moved to this area as a 10-year-old with his family from Pennsylvania in 1756. They attended what later became Thyatira Church. He was educated at the academy of Rev. David Caldwell in modern Greensboro before going to the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University. McCorkle graduated in 1772 and taught in other states before returning here as the minister in 1776, where he stayed for 30 years. He is believed to have suggested the church name, based on a town in Turkey the Bible says was visited by the founder of Christianity, Saint Paul.[6]

McCorkle was an active supporter of the Patriot cause. He also founded two area schools, but is better known for writing the petition that led to the creation of the University of North Carolina. He delivered the keynote address at the 1792 laying of the cornerstone for what today is called Old East, the university’s first dorm, in Chapel Hill. The main quadrangle there is McCorkle Place. Sadly, McCorkle was an invalid for the last ten years of his life, before dying at his home in 1811.

The Armies March By

Return to the main church driveway and look at the highway, NC 150.

During the Race to the Dan, Morgan crossed the Catawba River at Sherrill’s Ford west of Mooresville with the prisoners and most of his forces. As arranged with Greene, he then moved toward the Trading Ford across the Yadkin River on the other side of Salisbury. His force of roughly 800, many militia plus some regular Continental soldiers, took the route now covered by NC 150 from right to left early on Friday, February 2, 1781. It was freezing cold, and after days of rain, the road was pure mud. Morgan himself traveled in a wagon, laid out by sciatica and arthritis.

During the Race to the Dan, Morgan crossed the Catawba River at Sherrill’s Ford west of Mooresville with the prisoners and most of his forces. As arranged with Greene, he then moved toward the Trading Ford across the Yadkin River on the other side of Salisbury. His force of roughly 800, many militia plus some regular Continental soldiers, took the route now covered by NC 150 from right to left early on Friday, February 2, 1781. It was freezing cold, and after days of rain, the road was pure mud. Morgan himself traveled in a wagon, laid out by sciatica and arthritis.

The British, under Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis, pushed across at Cowan’s Ford (now the base of Lake Norman) and tried to cut Morgan off. But their army arrived at today’s Mooresville too late that same day. The next morning, you could have stood here and watched for hours as 1,850 Redcoats, their cannons, Loyalist refugees, escaping slaves, and camp followers passed by.

Francis Locke Homesite

Drive to NC 150 and turn left, following the two armies. Drive 2.9 miles and turn left on Briggs Road, just past the state historical marker for Francis Locke. Park on the shoulder. You may stay in your vehicle.

Look at the field to your left across the road.

Francis Locke bought 640 acres and had a home built here. It was probably close to NC 150 because in 1764, he started an “ordinary” (a tavern and inn) within the home. He was also a farmer, carpenter, and road surveyor.

Francis Locke bought 640 acres and had a home built here. It was probably close to NC 150 because in 1764, he started an “ordinary” (a tavern and inn) within the home. He was also a farmer, carpenter, and road surveyor.

In 1765 he was appointed Rowan County Sheriff, which was bad timing: It put him in direct confrontation with the Regulators, who were also complaining about corrupt county officials. He could only collect a third of taxes owed during his year-and-a-half tenure, and once was blocked from collecting a horse as payment by 15 men.[7]

After his retirement from the militia, he returned to full-time plantation life here. Locke held at least nine people as slaves, including Scipio, Charity, and Lott.[8] Apparently he studied law, because he was named a state attorney in 1794, only to die two years later.

More Information

- “A Guide to Some Historically Significant Gravestones in Thyatira Cemetery with an Easy System to Find Their Locations,” n.d., Thyatira Presbyterian Church

- Babits, Lawrence, and Joshua Howard, Long, Obstinate, and Bloody: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009)

- Barefoot, Daniel, Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1998)

- Brawley, James, ‘Locke, Francis’, NCpedia, 1991a <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/locke-francis> [accessed 23 April 2020]

- Brawley, James, ‘Locke, Matthew’, NCpedia, 1991b <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/locke-matthew> [accessed 2 November 2020]

- Garden, Alexander, Anecdotes of the American Revolution (Charleston, [S.C.] Printed by A. E. Miller, 1828) <http://archive.org/details/anecdotesofameri00gard> [accessed 7 May 2021]

- Inscriptions on Grave Stones in the Cemetery of Thyatira Church, 1755-1983, State Library of North Carolina, Government and Heritage Library

- Lewis, J. D., ‘The Patriot Leaders in North Carolina – Francis Locke’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2013 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/patriot_leaders_nc_francis_locke.html> [accessed 23 April 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘The Patriot Leaders in North Carolina – Matthew Locke’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2013 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/patriot_leaders_nc_matthew_locke.html> [accessed 3 November 2020]

-

‘Lieutenant George Locke (1752–1780), FamilySearch’ <https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/LCTK-1Z1/lieutenant-george-locke-1752-1780> [accessed 10 May 2024]

- Linn, Jo White, Abstracts of Wills and Estates Records of Rowan County, North Carolina, 1753-1805, and Tax Lists of 1759 and 1778 (Salisbury, N.C., 1980)

- ‘Marker: L-10’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=L-10> [accessed 11 February 2020]

- ‘Marker: L-20’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=L-20> [accessed 7 November 2020]

- ‘Marker: L-61’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=L-61> [accessed 2 November 2020]

- ‘Marker: L-62’ <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=L-62> [accessed 11 February 2020]

- McCorkle, Glenn, Thyatira Presbyterian Church, Interview with tour, 11/5/2020

- Pancake, John S., This Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas, 1780-1782 (University, AL : University of Alabama Press, 1985) <http://archive.org/details/thisdestructivew00panc> [accessed 13 October 2020]

- Taylor, Thomas, ‘McCorkle, Samuel Eusebius’, NCpedia, 1991 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/mccorkle-samuel-eusebius> [accessed 7 November 2020]

- ‘Thyatira’s History’, Thyatira Presbyterian Church, <https://www.thyatirapresbyterian.org/about/history/index.html> [accessed 11 February 2020]