The Moravians Navigate Neutrality

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 36.0838, -80.2432.

Type: Sight

Tour: Wachovia

County: Forsyth

![]() Full

Full

Though the sights on this page can all be viewed from public streets, you are encouraged to go through the exhibits at the Old Salem Museum & Gardens Visitor Center by the coordinates if open. You can purchase tickets to also visit building interiors during our tour, which is fully accessible, but interior access for those with mobility issues varies by building.

Unless otherwise noted, all information and quotations on this page come from single sources in the Records of the Moravians in North Carolina, primarily the official “diary” of the town for each year (see “More Information” below).

Context

Salem was completed in 1772 as the primary settlement of the 98,000-acre tract called “Wachovia” owned by the United Brethren, or “Moravians.” By 1776 it had around 75 people.

Salem was completed in 1772 as the primary settlement of the 98,000-acre tract called “Wachovia” owned by the United Brethren, or “Moravians.” By 1776 it had around 75 people.

Situation

Salem “was the center of commerce for the Upper Yadkin River valley,” and in coordination with outlying villages like Bethabara and Bethania, “the craftsmen and artisans there were capable of supplying the much-needed fresh meat, flour, salt, corn, and gunpowder…”[1]

The Moravians opposed bloodshed, and thus had to navigate neutrality in the face of demands from both sides throughout the war. Part-time soldiers known as “militia” mistrust the Moravians, at various times accusing them of helping their enemies. The Moravians try to walk the line between refusing help and providing too much to both Patriots (“Whigs”) and Loyalists (“Tories”). Soldiers and deserters from both sides regularly appear in Salem throughout the Revolutionary War.

But over the years it becomes clear the Moravians are leaning toward the Patriots, as when a bishop refers to the Continentals as “our” army in 1779. Later references in the Records often say “the” army in reference to them.

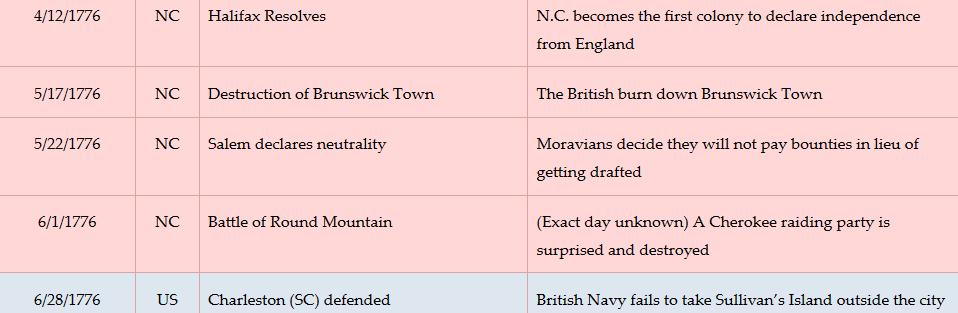

Dates

Wednesday, May 22, 1776–Sunday, February 25, 1781.

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

The Town Square

From the Visitor Center, go across the pedestrian bridge and down to South Main Street. Walk three right-side blocks to the fenced-in, grassy square. Continue about halfway up the block. (You can also drive this page’s route, though street parking may be limited.)

Look across the square to the building on the left that says Salem College, to the right of Home Moravian Church. During the Revolution this was the location of the Gemain (ge-MINE) Haus (“Community Hall”), used for general meetings as well as church services before the church was built in 1800.

Look across the square to the building on the left that says Salem College, to the right of Home Moravian Church. During the Revolution this was the location of the Gemain (ge-MINE) Haus (“Community Hall”), used for general meetings as well as church services before the church was built in 1800.

The Brethren men gather in the Gemain Haus on Wednesday, May 22, 1776, to make an important decision. All towns of the newly declared State of North Carolina are being required to furnish soldiers, or they can hire people to take their place. The Moravians refuse to serve in any war on religious principles. Men in Bethania, a nearby Moravian town, have suggested raising enough money to hire replacements. Instead, the men here unanimously decide, “We Brethren do not bear arms, and we neither will do personal service in the army nor enlist others to do it; but we will not refuse to bear our share of the burden of the land in these disturbed times if reasonable demands are made.” Starting in 1779, that “burden” becomes high, when the state triples the taxes of pacifist sect members like the Moravians.[a]

In a sense, the Gemain Haus was briefly the capitol of North Carolina two years later, and it played a minor role in one of the amazing stories of the Revolution. It was supposed to host a meeting of the General Assembly in late 1781. Acting Gov. Alexander Martin arrived, but not enough legislators. After waiting two weeks and weathering a Tory attack scare, the leaders left. They tried again in January with the same result.

The reason Martin was the acting governor is that Thomas Burke had been kidnapped in September! Imprisoned near Charleston, he escaped, and arrived here unexpectedly on January 25th because the legislature was here. After some debate in the Gemain Haus, he was allowed to resume his office. (See Hillsborough for the whole story.)

Patriots Make Demands

Continue across Academy Street at the end of the square, and go another block to Bank Street. As you pass the Winkler Bakery on the right, notice the empty lot across the street. The night watchmen’s house stood there in the war, mentioned in a later story.

Continue across Academy Street at the end of the square, and go another block to Bank Street. As you pass the Winkler Bakery on the right, notice the empty lot across the street. The night watchmen’s house stood there in the war, mentioned in a later story.

Cross Bank and then Main Street to the northwest corner, at another empty lot.

The second house built in Salem, started in 1766, stood here. It is referred to as “the two-story house,” suggesting it was the only one in town at the time. The basement is large enough to serve as a backup hotel for passing soldiers when the Tavern is full, as you will see.[2]

During the first part of the war, this is the home of Johann Fritz and his wife, and a girl they are raising whose mother had died. Fritz produces leather goods like gloves. Because he speaks English, he also has taken on preaching duties in the village of Hope, southwest of town along today’s Stratford Road to the west. Hope is known as “the English Settlement” because it was founded by four English-speaking Moravian families from Maryland.[3] (Most Moravians still spoke German.) In March 1780, the Fritzes move there to operate its new school.

The Fritzes survive a “fright” here from Patriot militia six months later, the Records say. By bad (or perhaps good) luck, they have returned here to the house on Thursday, September 14, for a meeting the next day. Around “ten o’clock when they were already asleep, Captain Holston and about sixteen men arrived, forced the door, and with drawn swords at their breasts ordered (the Fritzes) to open their chests.” Blowing out the lantern or candle, presumably so no one outside can see in, the raiders “took the clothing and linen from the chests.” They even rip Brother Fritz’s shirt off of him before some of them leave.

Fritz stands up to the rest, asking Holston whether “they robbed and plundered like Tories, and that from people whom they should protect?” This hits home. The chastened Holston and others, who know Fritz, promise to return the stolen items, saying the thieves were drunk. Indeed Holston gathers and returns everything overnight before leading his men across the Yadkin River the next day, to avoid Loyalists active in the area.[4]

Cornwallis Marches Through

Go back to and re-cross Academy to the corner across from the square. Look down Academy, away from the square.

The British army of Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis chased a Continental Army under Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene from west of Charlotte in early 1781. This was part of a campaign now called “The Race to the Dan.” Heavy rains blocked Cornwallis from crossing the Yadkin where Greene had near Salisbury, and he came the long way via Shallow Ford west of here.

The British army of Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis chased a Continental Army under Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene from west of Charlotte in early 1781. This was part of a campaign now called “The Race to the Dan.” Heavy rains blocked Cornwallis from crossing the Yadkin where Greene had near Salisbury, and he came the long way via Shallow Ford west of here.

On Saturday, February 10, the British army arrives up the street after an overnight stay in Bethania, and turns right at this corner to continue down Main Street.[b] First come the green-coated, heavily armed cavalry around 10 a.m. It takes six hours for the rest of the soldiers to file past you and down past the south end of the road, along with Tory refugees, camp followers, people escaping slavery, a few wagons, and cannons. (They continue to Friedberg southeast of town, and set up a camp that stretches two-and-a-half miles.)

Look at the Single Brothers House next to you. The section on the corner existed at the time.

The soldiers merely marched through, but the civilians did damage. The Records say, “The people who followed the baggage stole various things at the store and in the houses, for example the Single Brethren lost all their wash, Br. Meyer lost nine head of cattle, Br. Bonn lost £40.” That may not sound like much, but in modern money that is more than $7,000![5]

Going to the Store

Continue to the other end of the block and stop by the T. Bagge Merchant Store. Though it is not the original building, this was the location of the home and store of Brother Traugott Bagge (BAG-gee), at the time the vorsteher (mayor) of Salem.

Continue to the other end of the block and stop by the T. Bagge Merchant Store. Though it is not the original building, this was the location of the home and store of Brother Traugott Bagge (BAG-gee), at the time the vorsteher (mayor) of Salem.

Around 3:30 that afternoon, Cornwallis, Royal Gov. Josiah Martin, and other officers stop here, dismount, and go inside. They visit politely with Bagge and others for 90 minutes, as the last of the army is passing through.

With both the British and Continental armies in the vicinity at this time, small groups of soldiers from both sides pass through day after day. Once they do so on the same day, carrying flags of truce! So, too, do supply wagons and refugees, including formerly rich people trying to adjust to being poor. Around 100 Catawba Indians who had fought for the Americans camp outside town with their families one night. Sometimes all of these so-called “strangers,” meaning any non-residents, are described as “polite” or “friendly.” But often they steal from the Single Brothers House, bakery, tannery, blacksmith or store, while Patriot soldiers often put their bills on the public tab.

The store sold to everyone who came through, though “sold” was not always the right term. In mid-February of 1776, then-Capt. Benjamin Cleveland and about 200 men from the Surry County (Patriot) militia take what they want from the store and other locations, running a tab. “We could not object, though payment is doubtful,” the diarist moans.

On Sunday, February 25, 1781, the Salem Diary makes a point of noting, “There were no strangers in town all day, which is somewhat unusual.”

Stop in the shop next door to buy (not take!) something if you like. Then continue another block to the next-to-last house on the right before the driveway to the Tavern parking lot.

Stop in the shop next door to buy (not take!) something if you like. Then continue another block to the next-to-last house on the right before the driveway to the Tavern parking lot.

The location of the town shoemaker during the Revolution is unknown. But 714 Main Street is on the site of the shoemaker as of 1800 if not earlier, predating the current house.

Brig. Gen. Horatio Gates, commander of the Continental Army in the South before Greene, sent an order in 1779 for 1,000 shoes to Salem via a Maj. Hartmann. “The Major knew perfectly well that this was impossible, so he ordered a quantity of leather for uppers and for soles, which we should take to the army…”

The Tavern

Continue to the Salem Tavern Museum on the right. The current building was built in 1784 on the foundation of the original tavern, which existed during the war. A print of the Declaration of Independence arrived in Salem on Monday, August 6, 1776, and was posted on the tavern by a Patriot captain.[c]

An early test of the Moravians’ neutrality comes in the Summer of 1776, when a militia general demands they send soldiers for a campaign against the Cherokees. At Bagge’s request, the local militia commander talks him out of it, but some Moravians volunteer. On Sunday, November 24, an officer sets up at the tavern to pay area men for their service.[d]

An early test of the Moravians’ neutrality comes in the Summer of 1776, when a militia general demands they send soldiers for a campaign against the Cherokees. At Bagge’s request, the local militia commander talks him out of it, but some Moravians volunteer. On Sunday, November 24, an officer sets up at the tavern to pay area men for their service.[d]

Three years later, “about 150 horsemen and 30 foot (infantry soldiers), with three wagons” pull into town, on Friday, October 15, 1779. Apparently they are regular Continental forces, because they are “joined by a small company of militia from Guilford” (in modern Greensboro) and a few other Patriot militiamen. “All these men and their horses had to be fed. They kept good order, cooking in the open place by the Tavern in the heavy rain.” Ironically, that is where the former Salem Tavern restaurant sits now, to the left.

They ask for a worship service the next day, “so at twilight Br. Graff held a bright singstunde (‘ZING-shtunde’), in which voices and instruments joined in harmony, and at the close the New Testament benediction was sung” back at the Gemain Haus.

After the Battle of King’s Mountain (S.C.), a Patriot victory in October 1780, about 300 prisoners and their guards arrive in Bethabara. Officers are allowed to visit Salem with guards.

Among them is British Lt. Anthony Allaire. He had been allowed to ride here with Col. Isaac Shelby by way of Shallow Ford, arriving on the 22nd. He writes in his diary that he “‘went to meeting in the evening; highly entertained with the decency of those people, and with their music. Salem contains about twenty houses, and a place of worship. The people of this town are all mechanics… and all stanch (sic) friends to Government.’”[6] By “mechanics” he meant skilled craft workers and artisans, and by “friends” he meant, mistakenly, Loyalists.

Three weeks later, around 100 of the Tory prisoners from Bethabara, who have been released on condition of joining the Patriot army, pass through on the way to Salisbury.

Another example of how the Moravians served both sides happens Wednesday, November 10. Referring to Tory militia, the town diary records, “With them came about twenty English officers, and it looks as though they would remain here for some time. They were lodged in the Tavern, to which came also a number of sick soldiers with their doctor. Those who could not be lodged in the Tavern were placed in the large kitchen under Fritz’ house,” the two-story house you visited earlier. The diary writer was not yet aware the officers had escaped from Patriots in Bethabara five nights earlier!

As the Race to the Dan is unfolding to the south in 1781, around 4 p.m. on Sunday, February 4, about 170 Patriots from now-Col. Cleveland’s Wilkes County militia arrive on horseback. Their Capt. Herndon “first demanded brandy, which was furnished; then he wanted meat and bread or flour, and the flour was supplied; then he insisted on having meat, and some of that also was furnished. The militia men insist there is powder in the town… and that it must be given to them.” Capt. William Lenoir, who has seniority, arrives with more men and temporarily calms the soldiers down. However, the “requisitions began again about seven o’clock. In the Tavern many ate and drank as they pleased, and there they took three bundles of oats; the Single Brethren had to give them half an ox, 100 lbs. of meal, and several gallons of brandy; the store furnished corn and salt, the pottery had to supply ware, and in addition they took whatever came to hand. All these demands were made with threats, which sounded as though they sought an excuse to plunder the town.” They finally left around 10 p.m.

Salem having survived, mostly unscathed, the British march six days later, turns out to be a bad thing. Four days after that the Moravians hear a rumor that the local Whig militia—Stokes County at the time—wants to punish Salem, because the British did not plunder it as they had Bethania on the way here. These Patriots assume that means Salem’s residents are Tories! On Monday the 15th, two majors from the militia come to town by themselves, dine at the Tavern, and are friendly. That same day 200 Patriot soldiers from other counties pass through, and they and their horses are fed.

But the next day more of the Stokes militia begin coming into town, “and several were very troublesome, among them three or four who forced their way into the Gemain Haus, and were driven out with the help of the officers. Then they undertook to enter (Bagge’s) store, to see what they could steal, but this was prevented.” The Patriots also cause trouble here at the Tavern, by starting a fight, and down at the Single Brothers House.

Several officers from other counties are in town, including Capt. Joseph Graham. His detachment is passing through to join the Continental Army camped at Guilford Court House during the Race to the Dan. Graham’s unit arrives around noon. Graham is asked to help and agrees to try, but too much is going on. “The noise in town continued from morning to night; much was taken without payment or receipt. A Brother was stopped on the street, his coat was taken off his back and stolen; hardly one house remained unrobbed… Br. Yarrell escaped their hands through the aid of the officers. Br. Bagge was twice saved from them when they had a pistol at his breast…” It appeared they were trying to find proof of collusion with the British, so they could destroy the town.

Saturday, “two or three of the band, having eaten and drunk all they desired, roamed through the town all night, frightening now this and now that family, making them empty chests and show their contents, saying they were looking for powder which the English had left here. As they also asked about hard money, fine shirts, handkerchiefs, and the like, it was sufficiently clear what they really wanted, and much was stolen…”

They finally leave at 10 a.m. Sunday after stealing some horses. Church service had to be cancelled.

Surprising Cabins

Walk behind the tavern to where you can see the parking lot.

Walk behind the tavern to where you can see the parking lot.

Making those Patriot suspicions hard to understand are two buildings somewhere within your view downhill. In late January as the Race unfolded, a 24- by 30-foot rectangular log cabin is built behind the tavern. Gen. Greene had ordered this “laboratory” in which to mold ammunition, and the Brethren decide to build it “for the sake of the safety of the town.” A few days later they raise a second, smaller version as an ammunition storehouse or “magazine,” closer to the creek at the base of the slope across the modern road. This was for supplies from Salisbury, which was in the path of the British advance. Of course, they ended up in the path again, by a fluke: Had Cornwallis been able to cross the Yadkin at the Trading Ford that Greene used, he probably would not have come to Salem. The first three powder wagons arrive on January 20th with no place to go, and their supplies are put in the small house of the town’s night watchman. (That house was pointed out before, across the street from where the Winkler Bakery is now.)

The last day of the month, “Two wagons, loaded with powder, lead, and balls, and two cannon, (three-pounders[7]) came from Salisbury to the Continental magazine here. Colonel White and another officer arrived, to send to Virginia some of his men who have been quartered here, and to send the rest to the main body of the army.”

However, they are a little early. The magazine isn’t quite finished, and there has been an injury. Gottlieb Spach, 16, was helping with the roof at one end that day when “he took hold of an imperfect timber with one hand; it broke with him and he fell from the rafters, but only dislocated one shoulder and injured one hand.”[8] The building was not completed until the next day, “in the rain.”

No source reports what happened to these supplies. Since none say the British found them, either they were moved again before the Redcoats arrived, or the British didn’t think to look for them in a town they thought was Loyalist.

Go to the left to the exposed foundation. The small sign marks this as the smokehouse. It served a different purpose related to smell one day.

Continental Captain Paschke spends the night in the tavern on Tuesday, August 10, 1779, and leaves the next day. “He left a very sick soldier here to be nursed, but it was necessary to move the man from the Tavern into the adjoining smoke-house, as the stench was intolerable.”

Historical Tidbits

- The oldest recorded celebration of July 4th in Salem was not held until 1783, in the square—after negotiations had begun between the United States and Britain to end the war. The Moravians had maintained their official neutrality until the result was clear.

- During his post-war tour of the southern states, Pres. George Washington spent the night in the current Tavern building on May 31 and June 1st, 1791.

More Information

- ‘Cornwallis Visit 165 Years Ago Today’, Winston-Salem Journal & Sentinel (Winston-Salem, NC, 10 February 1946)

- Crews, C. Daniel, and Richard W. Starbuck, eds., Records of the Moravians Among the Cherokees (Tahlequah, Okla.: Cherokee National Press; Disbributed by University of Oklahoma Press, 2010).

- Crow, Jeffrey J., A Chronicle of North Carolina During the American Revolution, 1763-1789, North Carolina Bicentennial Pamphlet Series (Raleigh: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1975)

- Fries, Adelaide L., ed., Records of the Moravians in North Carolina (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton, 1922), 2 1752-1775 <http://archive.org/details/recordsofmoravia02frie> [accessed 17 March 2020]

- Fries, Adelaide L., ed., Records of the Moravians in North Carolina. Volume III: 1776-1779 (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton, 1926), iii <http://archive.org/details/recordsofthemora03frie> [accessed 17 March 2020]

- Fries, Adelaide L., ed., Records of the Moravians in North Carolina. Volume IV: 1780-1783 (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton, 1930), 4 (1780-1783) <http://archive.org/details/recordsofthemora04frie> [accessed 19 March 2020]

- ‘Fritz, Johann Christian’, Old Salem Museums & Gardens <https://www.oldsalem.org/item/wachovia/fritz-johann-christian/684/> [accessed 11 August 2020]

- Graff, Michael, ‘Time Stands Still in Old Salem’, Our State Magazine, 2012 <https://www.ourstate.com/old-salem/> [accessed 21 March 2020]

- Graham, William A. (William Alexander), General Joseph Graham and His Papers on North Carolina Revolutionary History (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton, 1904) <http://archive.org/details/cu31924032738233> [accessed 27 March 2020]

- Jones, Randell, Before They Were Heroes at King’s Mountain, North Carolina/Tennessee Edition (Winston-Salem, NC: Daniel Boone Footsteps, 2011)

- May, Kim, ‘Questions on Salem during Revolution’, E-mail, 11 August 2020

- ‘Our History’, Home Moravian Church <https://www.homemoravian.org/index.php/who-we/history/> [accessed 21 March 2020]

- ‘Salem Once Looked on as Redcoats Marched: 175th Anniversary of Winston-Salem, Route of the British Army, Feb. 10, 1781’, 1941 (Files, North Carolina Collection, Forsyth County Public Library)

- Schenker, Alex, ‘History Of Old Salem’, MyWinston-Salem.Com, 2014 <https://www.mywinston-salem.com/history-of-old-salem/> [accessed 21 March 2020]

- ‘Schmidt, Johann George’, Old Salem Museums & Gardens <https://www.oldsalem.org/item/wachovia/schmidt-johann-george/3582/> [accessed 11 August 2020]

- ‘Spach, John Gottlieb’, Old Salem Museums & Gardens <https://www.oldsalem.org/item/wachovia/spach-john-gottlieb/3830/> [accessed 13 August 2020]

- Van Hoven, William, Revolutionary War sites and activities in Salem, Phone interview, 3/21/2020

- Van Hoven, William, The Continental Magazine and English Settlement, Phone interview, 8/13/2020

[1] Jones 2011.

[2] May 2020.

[3] Fritz.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Nye, Eric, ‘Currency Converter, Pounds Sterling to Dollars, 1264 to Present’ <https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm> [accessed 18 September 2020].

[6] Jones.

[7] The weight of solid cannon balls they could fire, so these were small.

[8] Spach.

[a] Crow 1975.

[b] “Cornwallis Visit 165 Years Ago Today”; “Salem Once Looked on…”

[c] Crews and Starbuck 2010.

[d] Dean, Nadia, A Demand of Blood: The Cherokee War of 1776 (Cherokee, N.C.: Valley River Press, 2012).

← Bethabara | Wachovia Tour | Tory’s Den →