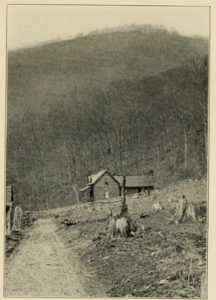

Home of the Hanging Patriot

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 36.2168, -80.9437.

Type: Stop

Tour: Wachovia

County: Wilkes

Drive to the end of Chatham Street in Ronda, and park before you reach the railroad tracks. The land discussed on this page is all private property, so you can stay in your vehicle.

Please see our Hurricane Helene page about possible impacts to this location from the 2024 floods.

Description

Col. Benjamin Cleveland built a house in 1771 on the far side of the hill ahead and to your right. Cleveland fit the stereotype of a frontiersman. Little is known of his early years in Virginia before he moved to Mulberry Fields, what today is Wilkesboro, at 31. In 1772 he and a hunting party ventured illegally into Cherokee territory, but were forced to leave by a warrior band with only the clothes on their backs—not even their hats or shoes—and one old gun with a couple of shots for hunting. They nearly starved. After recuperating from the difficult journey, Cleveland went back with a group and retrieved his horses with the help of other Cherokees. Cleveland was a friend of frontier legend Daniel Boone, who lived along the Yadkin where the Kerr Scott Reservoir is today, west of Wilkesboro.[1]

Col. Benjamin Cleveland built a house in 1771 on the far side of the hill ahead and to your right. Cleveland fit the stereotype of a frontiersman. Little is known of his early years in Virginia before he moved to Mulberry Fields, what today is Wilkesboro, at 31. In 1772 he and a hunting party ventured illegally into Cherokee territory, but were forced to leave by a warrior band with only the clothes on their backs—not even their hats or shoes—and one old gun with a couple of shots for hunting. They nearly starved. After recuperating from the difficult journey, Cleveland went back with a group and retrieved his horses with the help of other Cherokees. Cleveland was a friend of frontier legend Daniel Boone, who lived along the Yadkin where the Kerr Scott Reservoir is today, west of Wilkesboro.[1]

Cleveland was appointed to the Surry County court by 1774, which became the local government (“committee of safety”) after war broke out. Cleveland joined the local defense forces known as “militia” in 1775, and served in a campaign against the Cherokees the next year. After Wilkes County was formed a year later, he was named a colonel and commander of its militia regiment. In that role he played a critical part in the victory over a Loyalist or “Tory force” with the Overmountain Men at the Battle of King’s Mountain (S.C.).

Over the course of the war, one historian says, Cleveland “‘probably had a hand in hanging more Loyalists than any other man in America.’”[2] He was indicted for murder in 1779 but pardoned by the General Assembly and governor, barely.[a] It must be noted that some Tory leaders were equally bloody, and that Cleveland was not completely hard-hearted. One source reports that on capturing a Loyalist officer, Cleveland supposedly ordered his men, “‘Waste no time! Swing him off quick!’”

The unperturbed prisoner quipped, “‘Well, you needn’t be in such a damned big hurry about it.’”

Cleveland was swayed. “‘Boys, let him go,’” he said.[3]

Cleveland stars in a number of pages on this website, including two hanging sites, Bickerstaff’s Old Fields and the Tory Oak in today’s Wilkesboro. After the war he lost his property to a neighbor due to a loophole in the new state’s laws. Poor records and swindles from the colonial era had left land ownership a mess. The state issued new grants starting in 1778, giving legal rights to the first person to claim the land. Some filed grants for other people’s properties with phrases like, “‘where (current landholder) formerly lived,'” or, “‘including the improvements of (landholder)…'” Cleveland fought his neighbor’s claim in court, but lost.[b]

He moved to South Carolina, illegally into Native American territory. It was eventually annexed by force to that state. He died at home there at age 68.

What to See

The Round About

Named “The Round About” for the river bend surrounding it, Cleveland’s home here was a log cabin near where these railroad tracks approach the river again upstream (to the right).

Named “The Round About” for the river bend surrounding it, Cleveland’s home here was a log cabin near where these railroad tracks approach the river again upstream (to the right).

Zoom the Location map until you see the entire curve of the river around the hill. The house was on the left side, a little way down from where the river curves south, partway uphill.[4] He would use it as a mustering point for the militia, supposedly blowing a horn that could be heard in all directions from these heights.[5] He owned 10,000 acres as far west as the New River near Boone, plus “a grist mill on Roaring River (to the west) and a bridge over Elkin Creek” in modern Elkin.[6]

Later owners of the farm here pointed out a large sycamore tree that tradition claims Cleveland used for some of his hangings. If still standing, it is by the river on this side of the hill, along the dirt road you see from your vehicle going to the left of the hill.[7] (On the Location map, it is near where a small stream crosses the road right at the river.[8])

In the Spring of 1781, Cleveland was kidnapped, and then rescued at the Wolf’s Den near Boone. Three of the men were hung at the Tory Oak, and Cleveland’s party then caught up with a fourth, Zacariah Wells. Wells had wounded one of Cleveland’s men during the kidnapping. Though wounded himself and left for dead during the rescue, Wells had recovered.[9] An 1880s historian picks up the story. He says two boys, James Gwyn and an unnamed African-American, likely enslaved, were plowing a cornfield nearby. Cleveland took off the horse’s plow lines to hang Wells with them. Gwyn begged Cleveland not to hang him, but Cleveland is said to respond, “‘he is a bad man; we must hang all such dangerous Tories, and get them out of their misery.’” Soon Wells was swinging from the sycamore.[10]

Apparently Cleveland’s wife Mary was cut from the same cloth. A Loyalist horse thief was caught while Cleveland was away, and his boys, fearful of the thief escaping, asked their mom what to do. Puffing her pipe, she asked what their father would do, and you can guess their answer. “‘Well, then, you must hang him,’” she said. The thief was dropped from the house’s front gate.[11]

Trespassing is not a hanging offense, but please respect the current property owners’ rights anyway!

Passing Campaigns

The militia from Surry County, which still included modern Forsyth County around Winston-Salem then, likely passed within your view many times, highlighted by two known examples. It was not unusual for railroad tracks to be built on Native American trading paths, so the men may have ridden right in front of you! The first time was in August 1776, when they passed from left to right to join the campaign against the Cherokees which Cleveland was in. They returned in late October after helping destroy dozens of villages.

Four years later, about 100 men of the same unit rendezvoused in Elkin and passed by here. They were on the way to meet Cleveland’s troops at Mulberry Fields and then join the Overmountain Campaign. Both units, and some others, return in late October with more than 300 Tory prisoners bound for Bethabara in today’s Winston-Salem.

If you are taking the Wachovia Tour, you will parallel their route along the Yadkin most of the way to modern Lenoir.

More Information

- Absher, R. G., Mulberry Fields and the Overmountain Campaign, Phone interview, 9/28/2020

- Barefoot, Daniel, Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1998)

- Draper, Lyman Copeland, King’s Mountain and Its Heroes: History of the Battle of King’s Mountain, October 7th, 1780, and the Events Which Led to It (Cincinnati: Peter G. Thomson, Publisher, 1881) <http://archive.org/details/cu31924032752846> [accessed 31 March 2020]

- Guilford County: A Map Supplement (Jamestown, NC: The Custom House, 1988)

- Jones, Randell, Before They Were Heroes at King’s Mountain, North Carolina/Tennessee Edition (Winston-Salem, NC: Daniel Boone Footsteps, 2011)

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Benjamin Cleveland’, The Patriot Leaders in North Carolina, 2013 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/patriot_leaders_nc_benjamin_cleveland.html> [accessed 4 April 2020]

- Wadsworth, E. W., ‘The Ghost of Riddle’s Knob’, The State, October 1982

- Waugh, Betsy Linney, The Upper Yadkin Valley in the American Revolution : Benjamin Cleveland, Symbol of Continuity, Dissertation, University of New Mexico (Wilkesboro, N.C.: Wilkes Community College, 1971)

- Waugh, Betsy Linney, ‘Cleveland, Benjamin’, NCpedia, 1997 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/cleveland-benjamin> [accessed 4 April 2020]

[1] Absher 2020.

[2] Barefoot 1998; Lewis 2013.

[3] Draper 1881.

[4] Absher.

[5] This is also said about Rendezvous Mountain to the west, along NC 268, but there is no evidence to support that location.

[6] Jones 2011.

[7] Absher.

[8] Draper.

[9] Wadsworth 1982.

[10] Draper.

[11] Ibid.

[a] The bill passed two of the three votes required in those days, only after language was added villifying the victims before the third “reading” (Waugh 1971).

[b] Details and quotations are from “Guilford County” (1988), but multiple sources confirm the basic facts.

← Surry Muster | Wachovia Tour | Tory Oak →