Tories Hang and Militias Meet

Description

Go to the back-right side of the museum along Broad Street, at the corner with North Street (which runs behind the building).

Long before the Revolutionary War, this area was named Mulberry Fields by Native Americans. During the war a wooden community building, the Mulberry Fields Meeting House, stood on or near the current museum site.[1] (Though built by Baptists, by this time it was just a community building.[2]) In 1778, when Wilkes County was formed by the state legislature, this village was designated for the court house. Until one was built after the war, the meeting house served the purpose.[3] The county was much larger then, stretching north to Virginia and west all the way to the Great Smoky Mountains.

Look at the picnic table nearest North Street, between two trees. In the 1770s a large black oak tree stood on that spot.

In the fall of 1779, two Loyalists (“Tories”) raided the home of a Patriot farmer and stole his horses. Patriot militia (part-time soldiers) captured them and brought them to the Wilkes County jail somewhere nearby. Horse-theft was a hanging offense, but generally a trial was involved. Col. Benjamin Cleveland of the Wilkes County Militia skipped that formality. He had the Tories hung from the tree here.

Cleveland was captured in retaliation two years later, April of 1781. But he was rescued at the Wolf’s Den near Boone and three of his captors were brought back to this spot. Despite the apparent conflict of interest, Cleveland presided over their court-martial, presumably in the meeting house. Even though one of them, Loyalist Capt. William Riddle, had not taken his life when he could have, Cleveland did not return the favor. They were condemned.

Riddle attempted to appease the “court” by offering to buy a round of whiskey. Cleveland said it was a waste of time, because the men would be hung after breakfast. So they were, from what now is called the “Tory Oak,” with Riddle’s wife looking on.[4] Making things worse for both of them, one of the others was probably their 15-year-old son, Moses.[5]

The tree lived until 1992, when it was destroyed by disease and winds. However, it was not the only tree in the area to get a name from that time. Col. William Lenoir wrote that once when he was on business here, as he returned to his horse, he spotted a man running away from it. Lenoir chased and caught him. The man had stolen one of his stirrups. Lenoir brought the thief—ironically named Shad Laws—back to the meeting house. Without bothering with a trial, Cleveland had the man put his thumbs in the forks of a tree branch, and ordered Capt. John Beverly to whip him 15 times.

But Beverly did not stop at 15. Another captain tried to interfere, and when Beverly kept going, pulled his sword and hit him with it. Beverly then drew his sword, and others had to step in to stop a duel. The tree became known as Shad Laws’ Oak, and still stood in 1914 when this story was first published.[a]

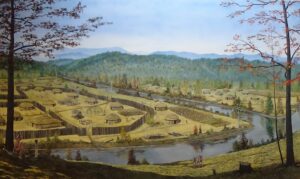

Visit the well-designed museum if you like, taking special note of exhibits on the Revolution, and a research-based painting of a Native American village shown below.[6]

Pass behind, or exit the back of, the museum along North Street to the other side. Cross Bridge Street and turn right. Partway down the block on the left is the 1859 jail, which formerly housed the museum. Turn left past it.

In front of you is the 1779 house of Cleveland’s brother Robert, which was moved here from roughly 8 miles northwest in the 1980s. Robert became a captain in the Surry County militia under his brother’s command in 1776. He stayed active though most of the war, switching to the Wilkes militia when the county was formed. He is known to have fought at the 1780 Battle of King’s Mountain (S.C.) and the Battle of Cowpens (S.C.) the next year.[7]

However, his greatest exploit was the rescue of his own brother. When Benjamin was captured by Riddle’s Loyalists, one group of his men followed them, while someone came to inform Robert at this house. He led a group of Wilkes militia that surprised the Tories at the Wolf’s Den just before Benjamin was possibly to be killed.

Behind the house is an entrance trail to the Yadkin River Greenway. It is wheelchair accessible, but a portion is steep. At the bottom, a bridge crosses the river. Go as far down as you want and look into the fields beyond.

In 1752 the German religious group known as the “Moravians,” by then living in Pennsylvania to escape persecution, had been offered land in North Carolina to expand their American presence. Their bishop, Augustus Spangenberg, went from Pennsylvania to Edenton with a survey group to meet the land agent for the owner, and then scouted through what now is northwestern North Carolina.[8] They came to a hill, possibly where North Wilkesboro is now (to your right), and looked down into this valley. By Spangenberg’s estimate, it was filled with 500 thatch-roofed homes and thousands of people. It’s unknown whether these were Cherokees or Catawbas. Given the large number, it may have been a temporary gathering for a corn festival.[9] Regardless, his group made the wise decision not to make contact!

In the museum painting pictured above, the river splitting the village is Readie’s River, down the trail to your right.

The Moravians did buy land here in addition to the “Wachovia Tract” that includes Winston-Salem. After a post-war dispute over ownership, they gave the land to the fledgling University of North Carolina. To build Wilkesboro, the county government apparently had to buy 50 acres around the meeting house twice, from UNC and from locals who had claimed them![10]

The Surry County militia marched from modern Elkin in September 1780 to help the Overmountain Men confront a British corps at Gilbert Town (near today’s Rutherfordton). They rendezvoused with Cleveland and the Wilkes regiment in the vicinity of modern Smoot Park[11], on the far end of North Wilkesboro. The combined force of about 360 men probably camped there on Thursday, September 27, 1780. Then Cleveland led them downriver on or near the modern greenway route along the Yadkin, right to left, on horseback. The same units returned in late October with more than 300 prisoners of the Battle of King’s Mountain in tow, bound for Bethabara (now in Winston-Salem).

They forded the river where Warrior Creek entered it west of town, now under Kerr Scott Reservoir.

More Information

- Absher, R. G., Mulberry Fields and the Overmountain Campaign, Phone interview, 9/28/2020.

- Arthur, John Preston, Western North Carolina, A History, 1730-1913, (Spartanburg, S.C.: The Reprint Company, 1973; first published 1914).

- Hartung, James, ‘Volume 4, Issue 1, December 1997’, The Riddle Newsletter, 1997 <http://jimsgenealogy.net/riddle/riddle/vol4is1.html> [accessed 20 October 2020]

- Jones, Randell, Before They Were Heroes at King’s Mountain, North Carolina/Tennessee Edition (Winston-Salem, NC: Daniel Boone Footsteps, 2011).

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Capt. Robert Cleveland’, The North Carolina Patriots, 2013 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/patriots_nc_capt_robert_cleveland.html> [accessed 29 September 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Wilkesboro, North Carolina’, Carolana, 2007 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Towns/Wilkesboro_NC.html> [accessed 1 October 2020]

- Queen, Louise, ‘Spangenberg, Augustus Gottlieb’, NCpedia, 1994 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/spangenberg-augustus> [accessed 29 September 2020]

- Staff, ‘Capt. Cleveland’s Story Told: New Sign near Log House Dedicated Saturday’, Wilkes Journal-Patriot, 2014 <https://www.journalpatriot.com/news/capt-cleveland-s-story-told-new-sign-near-log-house-dedicated-saturday/article_152c6224-848c-11e4-92bd-8769f773709f.html> [accessed 29 September 2020]

- Waugh, Betsy Linney, The Upper Yadkin Valley in the American Revolution : Benjamin Cleveland, Symbol of Continuity, Dissertation, University of New Mexico (Wilkesboro, N.C.: Wilkes Community College, 1971).

- Wilkes Heritage Museum, ‘Exhibits’ (Wilkesboro, N.C., 2020).

[1] Absher 2020.

[2] Waugh 1971.

[3] Lewis 2007.

[4] Jones 2011.

[5] Hartung 1997.

[6] Wilkes Heritage Museum.

[7] Lewis 2013; Staff 2014.

[8] Queen 1994.

[9] Absher.

[10] Lewis 2007.

[11] Absher.

[a] Arthur 1973.

← Round About | Wachovia Tour | Fort Defiance →