The Same, Yet Different

In some ways, North Carolina’s government is the same today as it was before and during the American Revolution. There was a governor, a council of advisors, and a legislature. There were local governments, and local and N.C.-wide courts. But their names, who could be in them, what they could do, and who could vote has changed. As you read this website, the differences can be confusing.

This page briefly outlines European-American governments across three phases of Revolutionary North Carolina starting in 1729, to help you make sense of the terms you will see. For context, we add two sections on how the colony started and another on today’s government.

The first governments in today’s North Carolina were those of various Native American nations. See our page on the Cherokees, one of the largest, for a little about their government structure.

Spanish explorers were the first Europeans to pass through and try to settle. They built forts in the 1560s near Quaker Meadows (now Morganton) and at the Trading Ford by modern Spencer. These were strictly military installations, however, and both lasted fewer than two years.

The first English charter related to North Carolina was granted in a “patent” to Sir Walter Raleigh in 1584. The patent authorized Raleigh to colonize any “remote, heathen and barbarous lands, countries, and territories, not actually possessed of any Christian Prince, nor inhabited by Christian People…”[1] This wording excluded the rights of the people who actually possessed these lands. Raleigh founded the first English colony on the North American mainland in 1585, on Roanoke Island near today’s Manteo. He named it “Virginia” for Queen Elizabeth, said to be a virgin. It was abandoned, and a few men left behind could not be found when Raleigh’s second group arrived in 1587. That one disappeared as well, and became known as the “Lost Colony.”

In 1629, British King Charles I gave his attorney general, Robert Heath, all of North America from the Caribbean to the Pacific Ocean between the 31st and 36th lines of latitude.[2] This covers the region from near the Virginia line to Florida, and was named “Carolana” in Charles’ honor. This patent ignored not only that Native Americans owned the land, but also the claims of the French and Spanish! However, Heath never landed colonists here, and transferred the patent to another English nobleman, who failed to do so as well. Thus the closest court for filing the first deeds in later North Carolina was in modern Virginia.

Forty years after a successful English colony started there, a landowner from Virginia made the next British foray. Nathanial Batts apparently bought land from Yeopims in the northeast corner of today’s N.C. as early as 1648. But he only lived there while trading with them. A patron had a combination home and trading post built for Batts around 1655. It was somewhere on what now is called Salmon Creek, across the Chowan River from modern Edenton (as shown on the map).

Batts’ ownership became legal in 1660 when a deed was recorded in Virginia for his purchase. (Notice that the county recognized Native Americans as the prior owners of the land.) This was the first act of British government in North Carolina.

One of the witnesses to Batts’ purchase, George Durant, bought a parcel soon after from a Yeopim chief between the Perquimmons and Little Rivers, to this day known as “Durant’s Neck.” Though not officially recorded until 1712, the related deeds were the first entered in a North Carolina court.

The Lord Proprietors

In 1663, King Charles II of England gave all of what now is North and South Carolina to eight wealthy supporters. These “Lord Proprietors” had helped him regain the throne after he was deposed. The Proprietors never visited Carolina, but each appointed a deputy, who apparently moved or lived here to represent him. Only a few hundred European-Americans lived in today’s N.C., mostly Virginia squatters here without permission. The large number of streams and swamps limited the available land and slowed growth.

In 1663, King Charles II of England gave all of what now is North and South Carolina to eight wealthy supporters. These “Lord Proprietors” had helped him regain the throne after he was deposed. The Proprietors never visited Carolina, but each appointed a deputy, who apparently moved or lived here to represent him. Only a few hundred European-Americans lived in today’s N.C., mostly Virginia squatters here without permission. The large number of streams and swamps limited the available land and slowed growth.

The charter granting the Proprietors the land, updated just two years later, treated Carolina as an extension of the feudal system. Under that, a nobleman was effectively the king of his land, answering only to Charles.[1] Charles alone could declare war, but the colony could raise part-time defense forces called “militia.”

At the Proprietors’ request, a noble named Lord Shaftesbury worked with John Locke to create the “Fundamental Constitutions” for Carolina. (Locke later become a famous philosopher and influenced the authors of the U.S. Constitution.) The documents generally mirrored the English social hierarchy of: the Proprietors at the top; then higher to lower levels of nobles; next, small property owners; then tenant farmers; and finally, slaves. However, the constitutions added personal rights like trial by jury and the freedom to create new (Protestant) churches outside of the official Church of England. Realizing the new structure would take time to establish, the Proprietors sent with the constitutions in 1670 a slimmed-down temporary version that was more closely followed.

Initially the Proprietors broke Carolina into three counties: Albemarle, north of Albemarle Sound; Craven, most of what now is South Carolina; and Clarendon, from the mouth of the Cape Fear River down to Craven (all named for Proprietors). However, Albemarle later was expanded to cover all of what now is North Carolina. When the constitutions were sent over in 1670, Albemarle was broken into “precincts,” which in time became what we now call counties[4]. Meanwhile a second county was formed, Bath. Not counting an indirect reference when the 1689 governor was named, the first official use of “North Carolina” came in the 1712 appointment document of Gov. Edward Hyde.[5]

In theory the legislature had a broad range of powers compared to today’s. In practice, due to the veto power given to the governor and the Proprietors’ deputies, it became an extension of them. However, the assembly had to approve “money bills” covering taxes and public spending, which put some limits on what the governor and deputies could legally do. Plus, as precincts were added over the years, and the lower house gained more representatives, the legislature gained more power.

Structure

- Governor—The deputy of the oldest proprietor was the overall governor of the province, seated at “Charles Town” (now Charleston). Because of the distance, Albemarle was given a Deputy Governor. The governor retained veto power over both the council and the legislature, described below. However, he—always a “he” in those days—needed approval from three deputies for many actions.

- Council—There was also a “council” that had different names in these years, including the “Grand Council.” Its membership changed four times through the Proprietary period, first appointed by the governor and at the end by the Proprietors, but it was always made up of large landowners. The deputies and council technically had separate powers. However, the deputies were always at least half of the council, and thus controlled it along with the governor.

- Legislature—The king’s charter required the Proprietors to assemble the “freemen” at unspecified times to approve laws. The lords interpreted that to give them almost complete control over how the assembly was formed and managed. The “Grand Assembly,” starting in 1665 as a single body, first met annually. It consisted of two delegates elected from each precinct, plus the deputies. By 1691, the assembly had split into two houses, and met every two years. The upper house was the council. The lower, called the House of Burgesses, was elected

- Courts—Before the constitutions arrived, the only court in Carolina was the governor and the council. When precincts were formed, so too were precinct courts appointed by the governor and council, who continued to serve as the only court of appeals. This was the system until at least 1695, but an Albemarle County court was in place between those levels by 1702. After then, the council retained some other legal duties in addition to its role as the supreme court.

- Local Governments—Due to the sparse population, there initially were no local governments. Residents went straight to the assembly or precinct courts depending on the issue. After towns began to be chartered, starting with Bath in 1705, these presumably had councils of some sort, but records are sparse.

Problems Arise

Until 1715, the two constitutions were loosely enforced. Residents had a high degree of independence. But they often resorted to force to settle disputes because there were so few courts; roads and bridges developed slowly; a consistent response to security concerns like pirates and the Spanish was difficult; and there was no safety net for the poor. North Carolina in particular had a high percentage of squatters and indigents. These included people who could not find land in Virginia after large landowners took most of it, and others in England given a choice between prison and getting shipped to America![6]

Governors in colonial N.C. were regularly kicked out for corruption, such as one who grabbed 46,000 acres for himself and was eventually banished. Subtracting his eight-year term, the colony went through 40 governors in 56 years. (For comparison, South Carolina “only” had 25.)[7]

From Private Property to Province

In 1729, the king’s administration (the “crown”) convinced seven of eight Lord Proprietors to sell their lands back to it. The four northern sections had already come to be called “North” Carolina, but this action made the split official, creating the “Province of North Carolina.” Lord Granville, owner of the 60-mile swath nearest Virginia, refused to sell to the crown, but eventually parceled it out to various buyers.

A more formal government structure was put in place modeled on England’s other colonies. As before, the only elected roles were the delegates to the lower house of the assembly. Any free male (including blacks) 21 or older who had resided in their election precinct for a year, and paid taxes the year before, could vote. Each voter initially had five votes to spread among the candidates for the House of Commons, but their choices were not secret—each person signed his ballot.

Structure

- Governor—The governor was appointed by the crown for an indefinite term, and was part of the court’s administration. Along with the typical executive functions of today, including having veto power over laws, he could call together the legislature, prevent it from meeting, and even disband it and call for new elections.

- Council—The governor was assisted by a “Council of State,” also appointed by the crown. Some policies of the governor had to be approved by the council, and it took part in many executive functions like appointing local officials and monitoring tax collection. These men also doubled as the upper house of the legislature, known as the “House of Lords.”

- Legislature—The legislature was officially the “General Assembly” like today, but was also called the “Provincial Assembly” at the time. (Historians often use that term, so AmRevNC does as well.) Laws passed between 1743 and 1760 placed more power in the assembly, especially over the courts, but the basic structure of the government stayed the same. The lower house was called the “House of Commons” and was elected. Proposed laws usually started in the House of Commons, including tax and spending laws. Each bill was read and voted on three times. It could be modified with each “reading,” and had to pass two out of three times in each house to become law. The crown and Parliament could not levy taxes; instead they assessed the provincial government to pay for crown services in the province.

- Courts and Local Governments—When you see a reference to the “county court” before and during the Revolution, that means the same thing as the county government. Court “justices” were both judges and the equivalent of modern county commissioners, and were appointed by the province. In addition to court duties, justices appointed or nominated local officials, collected taxes and fees, and oversaw road construction, among other tasks. There were a number of other court systems, like today, but only one played a significant role in pre-Revolution debates: the admiralty court, appointed by a board in England, and out of the control of the provincial government. It heard cases related to shipping, but the specific types of cases became a point of contention.

Conflicts Arise

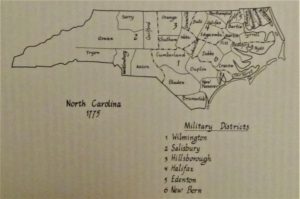

Among the problems of this structure was that early coastal counties had unfair power in the House of Commons: They were allowed five representatives each, counties in the southeast three, and western ones only two each. This contributed directly to the rebellion by the Regulators in the late 1760s.

The lack of secret voting made it easy for leaders to apply pressure or buy influence. In fact, voting became even less secret in 1760! After then, votes were cast verbally in the courthouse, in front of county officials. These practices allowed corrupt “courthouse rings” of large landowners—many of them justices of the peace and members of the assembly—to control the local governments and hold multiple county offices (a chief complaint of the Regulators). Justices appointed themselves to roles that made money because users, not general taxes, paid for the services.

In theory the provincial government continued until the official end of the war with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. In reality it disappeared when Royal Gov. Josiah Martin fled to Fort Johnston (today’s Southport) in 1775, and then offshore.

A Temporary Government

During the struggles between Martin and the Provincial Assembly, a group of property owners from the Cape Fear region invited the other counties to elect delegates to a “convention,” which later called itself the “Provincial Congress.” The majority of those elected were also assembly members, however. The first convention recommended that local leaders form five-member “committees of safety” to organize resistance to Parliament. (See, “What was the American Revolution?”).

Structure

After Martin left, the single-body convention became the legislature. In its fourth meeting, as the Provincial Congress, it declared support for independence through the Halifax Resolves of April 1776 and created a temporary constitution. As for the other roles:

- Council—Men were elected from the convention to run the colony until a formal state constitution could be written. This “Council of Safety” was the executive branch. The state was divided into six multi-county districts. Each had two delegates on the council, picked by the district’s congressmen. The congress picked a 13th.

- Governor—There was no governor. The closest to that role was the president of the council, Cornelius Harnett, elected by the legislature. But he was more of a committee facilitator than an executive.

- Local Government—Each district also had its own committee of safety. The county and town committees were the local governments. Supposedly these were elected by voters, but as before, they were dominated by large landowners. Notably, the congress said those committees could not inflict physical punishment beyond imprisonment, a response to excesses reported during the build-up to revolution (see for example the page on Edenton).

- Courts—Records from the time suggest the formal courts of before suspended operations, so the committees of safety also took over those duties.

The State Forms

The Fifth Provincial Congress was really a state constitutional convention. Delegates convened in November 1776 in Halifax and approved the new constitution the next month, creating the structure described below. Elections were held immediately after. The assembly appointed people to the governor and council roles on a temporary basis, until the new government took power in January 1777. That government formally joined the United States under an agreement called the “Articles of Confederation,” by ratifying them in April in New Bern.[8]

A key inclusion in the constitution was a separate “Declaration of Rights,” similar to the Bill of Rights added later to the U.S. Constitution. This provided some legal rights for free males not available in Britain. Among those, the delegates wrote in “that all persons shall be at Liberty to exercise their own Mode of Worship,” though only Protestant Christians were allowed to hold government office.

Structure

- Governor and Council—The governor and Council of State were elected by the legislature. No doubt in reaction to the assembly’s struggles with the royal governors, the state governor was given little power. For example, he—only males were eligible—could not appoint lower officials or veto laws passed by the legislature. He was, however, the commander of the state militia. To be governor, one source says, you had to own at least £1,000 of property (around $175,000 in modern money), though in practice they had much more.[9]

- Legislature—This was named the “General Assembly.” A major issue during the constitutional debates was the makeup of the upper house, to be called the “Senate.” The western counties, especially Orange and Mecklenburg, pushed for broader membership and voting rights. In the end, Eastern plantation owners won out again. They forced higher land ownership to be in the senate, 300 acres, and even just to vote for senators, 50 acres. Representatives had to have 100 acres, but their voters only needed to have paid taxes the year before. Voters for both houses also had to be free males, including blacks, 21 or older, residing in the election precinct for a year.

- Local Government and Courts—As before, the county courts were the official local governments. Now the justices were recommended by assembly delegates and appointed by the governor.

A More Representative Democracy

Although the basic structure of the government remains the same, the N.C. Constitution has been amended many times. Virtually all roles are elected. Any U.S. citizen 18 or older with permanent residence in the state and without a felony conviction can vote. There are no property requirements to vote or to hold office, though a candidate must have lived in the applicable region a set amount of time. And, votes are secret!

Structure

- Governor—The governor is elected by all voters, and has more power than the early state governors, including veto power over laws. However, governors have less power than they did during the colonial period.

- Council—The major department heads are still called the Council of State, but they, too, are elected. However, there is a separate cabinet of lesser department heads appointed by the governor.

- Legislature—Both houses of the General Assembly, now called the Senate and “House of Representatives,” are elected. There are more than twice as many House members as senators, but the districts in both cases are based on population. Therefore, districts may include part of or all of a county, or multiple counties.

- Local Government—The biggest change is at the local level, where government duties in towns and counties are overseen by voter-elected committees under various names. Mayors are chosen by voters, but county commissioners elect their chairs.

- Courts—The court system is now completely separate from the governor and assembly, other than depending on them for funding. The courts only handle lawsuits and criminal cases. The justices of the Supreme Court are elected, as are most lower-level judges.

Unless otherwise footnoted, most of the colonial- and Revolutionary-era sections summarize the one comprehensive source found, a state-published booklet from the U.S. bicentennial celebration (Ganyard 1978). The panel on the Proprietary years is supplemented by an 1894 book (Bassett), and basic facts on the page were corroborated with multiple newer sources.

- Barefoot, Daniel, Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1998)

- Bassett, John S., ‘The Constitutional Beginnings of North Carolina (1663-1729): Electronic Edition’, 1894 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/bassettnc/bassettnc.html> [accessed 26 December 2020]

- Butler, Lindley, North Carolina and the Coming of the Revolution, 1763-1776 (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1976)

- Charles I, ‘Charter Granted by Charles I, King of England to Robert Heath for Volume 01, Pages 5-13’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1629 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr01-0002> [accessed 9 July 2022]

- Charles II, ‘Charter Granted by Charles II, King of England to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, Volume 01, Pages 20-33’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1663 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr01-0009> [accessed 9 July 2022]

- ‘Colonial Period Overview’, NCpedia <https://www.ncpedia.org/colonial-period-overview#refs> [accessed 26 December 2020]

- deRoulhac Hamilton, J.G., ‘The County in North Carolina: Its Origin, Place, and Functions’, in County Government and County Affairs in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1918)

- ‘Exhibits’ (presented at the Museum of the Cape Fear, Fayetteville, N.C., 2020)

- Ganyard, Robert L., The Emergence of North Carolina’s Revolutionary State Government, North Carolina in the American Revolution (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1978)

- Isenberg, Nancy, White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America (New York, NY: Viking, 2016)

- Kelly, Martin, ‘The Founding of North Carolina Colony and Its Role in the Revolution’, ThoughtCo, 2020 <https://www.thoughtco.com/north-carolina-colony-103877> [accessed 21 November 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Carolina – The Virginian Settlers’, Carolana, 2007 <https://www.carolana.com/Carolina/Settlement/virginian_settlers.html> [accessed 21 November 2020]

- McIntosh, Atwell, ‘The County Government in North Carolina’, in County Government and County Affairs in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1918)

- ‘Minutes of the North Carolina House of Commons, North Carolina, General Assembly, April 14, 1778 – May 02, 1778, Volume 12, Pages 655-764’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr12-0006> [accessed 1 July 2021]

-

Powell, William, North Carolina: A History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988)

- ‘Queen Elizabeth I: Charter to Sir Walter Ralegh, 1584 [Raleigh]’, 1584 <http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/raleghcharter1584.htm> [accessed 5 August 2022]

- Rankin, Hugh F., ‘North Carolina in the American Revolution’, 1959 <http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/North_Carolina/_Texts/RANNAR/home.html> [accessed 25 January 2020]

- The North Carolina Booklet (North Carolina Society of the Daughters of the Revolution, 1904)

- Watson, Alan, ‘Settlement of the Coastal Plain’, NCpedia, 1995 <https://www.ncpedia.org/history/colonial/coastal-plain> [accessed 21 November 2020]

- Waugh, Betsy Linney, The Upper Yadkin Valley in the American Revolution : Benjamin Cleveland, Symbol of Continuity, (Dissertation, University of New Mexico (Wilkesboro, N.C.: Wilkes Community College, 1971)

[1] “Queen Elizabeth I…”

[2] Charles I 1629.

[3] Bassett 1894.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Powell 1988.

[6] Isenberg 2016.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Minutes of the North Carolina House of Commons.” State delegates to the Continental Congress signed the articles on July 21 in Philadelphia.

[9] Powell 1988; current value from: Nye, Eric, ‘Currency Converter, Pounds Sterling to Dollars, 1264 to Present’ <https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm>.