Patriot Women Take Tea and a Stand

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 36.0617, -76.6072.

Type: Sight

Tour: Rebellion

County: Chowan

![]() Full

Full

Park at the Historic Edenton State Historic Site Visitor Center. If it is open, consider going inside to ask about tour times: Getting into a couple of the buildings on this page requires a guided tour.

The state’s excellent tour guides cover a broader range of town history. Unfortunately they will overlap quite a bit with this page’s tour. You could use the page to get more details specific to the Revolution during a guided tour. But the page will be especially useful to those arriving when the site is closed or primarily interested in the Revolution.

All stops can be reached on pavement or by vehicle.

Context

The first permanent capital of North Carolina was the scene of early rebellion against King George III.

The first permanent capital of North Carolina was the scene of early rebellion against King George III.

Situation

Native Americans lived in this area for centuries before the first Europeans explored the bay in 1658, and Tuscaroras were here as late as the 1740s before moving north.[1] Possibly incorporated as early as 1715, Edenton was named the first permanent capital of the Province of North Carolina in 1722. Though that effectively moved to Brunswick Town in 1754, Edenton remained an active port in the 1770s, hosting an average of a ship per day.

Dates

Wednesday, August 22, 1774–April 1781.

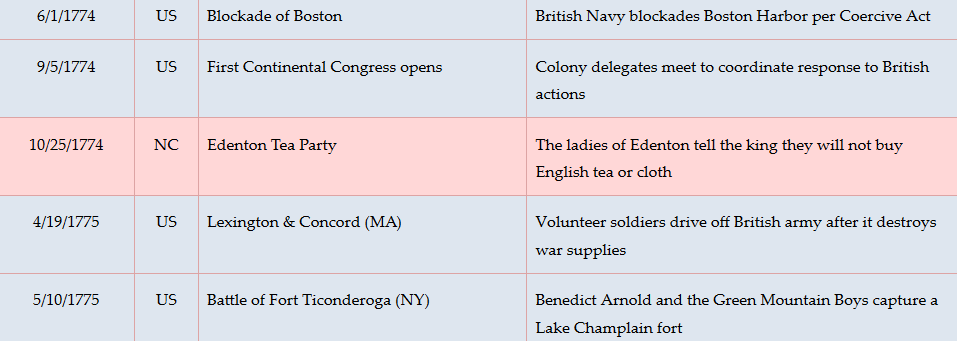

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

A Justice Sires a Governor

Walk to the opposite corner of the parking lot from the Historic Site center. The gate in the picket fence takes you behind the Iredell House. If the gate is locked, go around to the right past the post office to Church Street. Either way, go to the front left of the house, by the street.

Walk to the opposite corner of the parking lot from the Historic Site center. The gate in the picket fence takes you behind the Iredell House. If the gate is locked, go around to the right past the post office to Church Street. Either way, go to the front left of the house, by the street.

This house built in 1773 became the home of the regional collector of port fees and import taxes, James Iredell, Sr., three years later. He also was a part-time lawyer who studied under Patriot leader Samuel Johnston (introduced below) and married his daughter. Iredell had a speech impediment. Rather than let it stop him from becoming a lawyer, he apparently turned it to his advantage. Iredell was late to the idea of independence, though he disagreed with Parliament’s legal moves against the colonies. Still, after North Carolina became a state, Iredell served on the supreme court and then was attorney general from 1779-81. After the war, he wrote well-read pamphlets in support of the U.S. Constitution. He then became a U.S. Supreme Court justice. Iredell County, formed in his lifetime, was named for him. His son James, Jr., was born here and grew up to become governor of the state.

The part of the house with a porch front is probably the original section. Political discussions would most likely have taken place in the parlor in the back right corner. Behind the house are various outbuildings common for nicer homes of the day, such as a kitchen and a smokehouse.[2]

Continue past the house on Church Street. Walk to the second right, Oakum Street, and turn right. Walk one block to Queen Street. Cross it and turn left. Walk about halfway down the block to 306 E. Queen Street on the right, which is a private home.

This small home is the oldest known house in North Carolina. The logs used to build the 16-foot x 25-foot core section were felled in the Winter of 1718-19. Originally, and perhaps still during the Revolution, it was a log cabin with a whitewashed interior, two rooms below and above, and a chimney on each end.[3]

Drama at the Courthouse

Walk back along Queen Street 1-1/2 blocks to Court Street and turn left. Walk two blocks to King Street. Go to the front of the brick building on the right, the Old Chowan County Courthouse. (You might be able to see inside as part of the Historic Site tour.)

Walk back along Queen Street 1-1/2 blocks to Court Street and turn left. Walk two blocks to King Street. Go to the front of the brick building on the right, the Old Chowan County Courthouse. (You might be able to see inside as part of the Historic Site tour.)

Built in 1767, this is the second courthouse on the site, replacing a 1716 wooden one. It still sometimes hosts court sessions and thus is the longest-used courthouse in the United States.

The people of Edenton were early protestors against the collection of laws passed by the British Parliament known in the colonies as the “Intolerable” or “Coercive Acts.” Among other actions, these closed the port of Boston, Mass., in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party.

On Wednesday, August 22, 1774, a large crowd gathers here. Presumably they have just learned about those acts, passed in London on March 31. In a rowdy meeting led by the vicar of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, the crowd proclaims solidarity with the people of Boston. This is likely held in the second-floor room used for town meetings, official receptions, and as a ballroom. The room was believed to be “the largest fully paneled room in the American colonies” when it was built.[4] (Or, the meeting may have been held outside on the green behind you.)

Patriotic fervor overboils the following May, according to a state booklet.[5] A suspected Loyalist, Cullen Pollok, is brought before the Edenton Committee of Safety, effectively the local government after the collapse of the provincial court system, in the downstairs courtroom. Accused of an “unpatriotic remark,” he defends himself successfully after spending a night in the jail directly behind the courthouse. However, he also insulted some leaders of the local “militia” (part-time defense force). They and a group of soldiers go to Pollok’s house at 4 a.m., and drag him back here. Within sight of you, they pour heated tar over him and cover him in feathers, an act that usually leaves its victims scarred for life (if not dead). His wife followed them, and nearly faints in distress. The group then takes him home, drinks his liquor, and forces him to give them money. Local Patriot leaders apparently intervene to prevent destruction of the house, and one shelters them.

“Proof of Their Patriotism”

Cross King Street and turn right. Walk a short distance and turn left down the road that borders that side of the grassy town square. Walk about one-third of the block to the memorial on the right with a bronze teapot atop a small cannon barrel.

Cross King Street and turn right. Walk a short distance and turn left down the road that borders that side of the grassy town square. Walk about one-third of the block to the memorial on the right with a bronze teapot atop a small cannon barrel.

The house of Elizabeth King was on this lot when the 1774 meeting took place. Two months later, on Thursday, October 25, you see well-dressed women coming from all directions and entering the house. Perhaps they are greeted at the door by wealthy double-widow Penelope Pagett Barker, the organizer of this event. The house is small, so maybe a dozen squeeze in. There, supposedly over cups of herbal, lavender, and mulberry tea—not English black tea—they discuss what they can do to support the growing resistance to the British Parliament.

The month before, the colony’s Provincial Congress had passed a resolution to boycott British cloth and tea. The women decide to take action within the area of life they mostly control, according to the customs of the day: the “private sphere” of their homes. They write up a petition to King George. In a cover letter written two days later, perhaps it is Barker who says, “many ladies of this province have determined to give memorable proof of their patriotism, and have accordingly entered into the following honourable and spirited association. I send it to you to shew (sic) your fair countrywomen, how zealously and faithfully, American ladies follow the laudable example of their husbands, and what opposition your matchless Ministers may expect to receive from a people thus firmly united against them.”

Mentioning the congress’s resolution, the ladies declare: “‘As we cannot be indifferent on any occasion that appears nearly to affect the peace and happiness of our country… it is a duty which we owe… to do everything as far as lies in our power, to testify our sincere adherence to the same; and we do therefore accordingly subscribe this paper, as a witness of our fixed intention and solemn determination to do so.’”[a]

The initial group circulates the petition among other women of the area and ends up with 51 signatures—though not Mrs. King’s, for some reason. The mere fact there are 51 women in Edenton who can read and write suggests how well-off the town is, given that only a quarter of men in N.C. are literate at the time, and education for women is discouraged.[6]

The document is then sent to the king in London. A newspaper there publishes it in January, and the fact women are expressing themselves politically creates a sensation. (Some historians consider this the first major political action organized by European-American women.) James Iredell’s brother Arthur wrote him from England, “‘Is there a Female Congress in Edenton too? I hope not, for we English-men are afraid of the Male Congress, but if the Ladies, who have ever… been esteemed the most formidable Enemies, if they, I say, should attack us, the most fatal consequences is [sic] to be dreaded.’”[b]

The papers in England made fun of what became known as the “Edenton Tea Party,” including the unflattering cartoon shown here. Modern sources mistake the language from the cartoon for the wording of the actual petition. The event was largely forgotten in the United States, until a naval officer on a stop at a Mediterranean island “picked up in a shoe maker’s shop” a glass picture of the cartoon in 1826. He brought it back for his mother, an Edenton native.[c]

The papers in England made fun of what became known as the “Edenton Tea Party,” including the unflattering cartoon shown here. Modern sources mistake the language from the cartoon for the wording of the actual petition. The event was largely forgotten in the United States, until a naval officer on a stop at a Mediterranean island “picked up in a shoe maker’s shop” a glass picture of the cartoon in 1826. He brought it back for his mother, an Edenton native.[c]

The cannon the teapot sits upon is a British brass “three-pounder,” named for the weight of cannon ball it shot. This was a typical “field piece” used by armies, including in a number of battles on this website. There are eight cannons scattered about town, none of which saw action here.

The Town Green

Turn around, and step into the grass across the street if you wish.

Turn around, and step into the grass across the street if you wish.

You are amidst a prosperous town: “At the eve of the American Revolution the town consisted of approximately 177 dwellings and had its own silversmiths, blacksmiths, tailors, cobblers, bakers, indeed artisans of all trades: the waterfront seethed with activity; the town’s grog-shops and inns were packed with roistering sailors.”[7] It stretches about eight blocks back from the water, but the “blocks” are “rendered irregular… from the positioning of the houses, all of which had their own garden and pasture lots, outbuildings, and such.”

This block is the village green. Besides its use as a training ground for the militia, it is also where the stocks and whipping post for punishing wrongdoers are placed, probably on the end nearest the courthouse.

In early 1781, as the British army of Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis is chasing the Continental Army through the Piedmont far to the west, a colonist writes that area enslaved people are spreading stories. “‘They say people are getting ready to run again and the English are to be in Edenton by Saturday,’” she says.[8] Escapees who made it to British camps were generally allowed to go with those forces to freedom.

Rumors return in mid-April, when the British corps holding Portsmouth (near Norfolk, Va.) is said to be headed south.[d] Panicking citizens gather here on the green to decide what to do, mostly women and the elderly: Males of fighting age are either in the regular army or serving with militia called out to oppose the march. At some point a boat arrives from Windsor to the west, which offers the citizens refuge. Overnight there is a flurry of packing and other preparations, and by dawn, the residents and livestock are gone! For a week Edenton is a ghost town.

Soon after, Cornwallis is marching north from Wilmington. One source says the town crier hits the streets to announce that Cornwallis plans to send a detachment to burn Edenton for its role in the Revolution.[9] Another rumor holds that he has sent out 600 black foragers to plunder Patriot properties. Apparently the locals have learned their lesson and stay put. Neither attack happens, and the Redcoats get no closer than modern Rocky Mount on their way to Virginia.

A Working Waterfront

Walk down to the waterfront, view the Joseph Hewes Monument if you wish, and then cross over Water Street to the three cannon. Look into the harbor.

Walk down to the waterfront, view the Joseph Hewes Monument if you wish, and then cross over Water Street to the three cannon. Look into the harbor.

It is hard to imagine how busy today’s quiet bay was in the 1770s:

“Edenton’s waterfront was lined with wharves and warehouses, and the storefronts were operated by a surprisingly cosmopolitan lot of merchants: the Swiss Borritz, the German Kock, the Frenchman Peyrinnaut, the Scot Littlejohn, the Irishman Bennett, and many others. On the (east) side of town at the point where Pembroke Creek meets Edenton Bay, Joseph Hewes, one of Edenton’s foremost maritime merchants, operated a large shipyard capable of producing sloops of up to 200 tons.”[10]

A visiting German explained that British blockaders were unwilling to navigate the dangerous waters between here and the ocean. “‘Thus most of the American trading ships took refuge here… Philadelphia merchants established themselves here; the Virginians brought thither their tobacco by land-carriage, taking in exchange West Indian and other wares…’” Small blockade runners crossed to and from the French West Indies. By the end of the war in 1783, with larger ports open again, many of these lay rotting in the harbor.[e]

The largest wharf ran straight ahead of you into the bay, and there were four “finger wharves” spaced off to the right. The bottom remains lined with ballast stones, used to stabilize ships without full cargoes and dumped overboard as they were loaded.[11]

The shipping numbers bring the place alive:

“In the first half of the 1770s alone 827 ships cleared port carrying a multitude of cargo amounting to some ten million staves (wood strips for barrels), sixteen million shingles, 320,000 bushels of corn, 100,000 barrels of tar, 24,000 barrels of fish, 6,000 hogsheads of tobacco and a great variety of other produce; the same ships brought cargoes of trade goods to Edenton, principally rum (250,000 gallons), molasses (100,000 gallons), sugar (600,000 pounds), salt (150,000 pounds), linen (400,000 yards), along with silver tableware, brass candlesticks, Chippendale furniture, and books and magazines.”[12]

Perhaps among those numbers are “2,100 bushels of corn, 22 barrels of flour, and 17 barrels of pork collected from nearby counties” and sent to Boston in September 1775.[13] The shipment was arranged by the committee of safety, in response to the Coercive Acts.

Despite the Cornwallis rumor, no military action took place on land in the Edenton area during the war. There were, however, two naval incidents.[14]

In 1781, a large British “row galley” has been attacking Patriot boats in the Chowan River (which passes the right side of town as you face the water). It runs aground here in the harbor in June. Local militia row out to it and capture the crew. Then someone realizes the captain is a traitor: Capt. Michael Quinn served in the Continental Army from 1776–78, but switched sides, perhaps angered when he was called up again by the Patriot government. He is held in the local jail initially, and later marched off to then-prosperous Williamston, N.C.

While in custody there, Quinn was murdered by his guards on orders from their colonel. They were never charged, and the governor pardoned the colonel.

Six months after Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Va., a group of Loyalist merchants decide it would be okay for them to resume their old business activities. They arrive on a ship from Charleston and drop anchor in the harbor on Friday, February 25, 1782. On board is a cargo worth £80,000 (roughly $14.5 million today).[15]

They were wrong. A Patriot privateer, a state-sanctioned pirate, immediately seizes the Tory ship.[16]

Look at the artillery.

These cannons were imported for the Revolutionary War, but never fired a shot. They were part of a large shipment of artillery arranged in Paris in 1777 by diplomats including Benjamin Franklin. In July of the next year, you see a large ship pull into the harbor, owned and captained by Wilhelm (“William”) Borritz. He had moved here the year before from Sweden—not Switzerland, as many sources claim.[i] He picked up the cannons in Spain, working as an agent for the company that made them. They were supposed to be delivered to Virginia or ports north. But another ship Borritz owned, carrying 135 of the cannons, was captured by the British off Chesapeake Bay. This may explain why he decided to bring the remaining 45 here!

However, payment is delayed. Months pass. Finally, half the cannons are purchased by Virginia and removed from the ship by rowboats to the wharf. North Carolina bought the other half, some to resupply Fort Johnston in today’s Southport, which had been stripped by the British early in the war.[17] But the state could not pay for all of them immediately. Some sources claim Borritz tired of waiting and dumped a number into the harbor, but state records indicate all were delivered.[ii] Still, it’s unclear how many actually left town. Five years would pass before he received full payment, in the form of barrels of tobacco for resale.

These cannons were supposedly recovered from the bottom after 1785, though it’s possible they were just in storage. They were mounted here in 1861 as a Confederate defensive battery during the Civil War, only to be manually disabled by a United States gunship crew the next year.[18]

Look to the left corner of the bay, where a small bridge arcs over Pembroke Creek before it empties just past Queen Anne’s Park.

Now hidden within a gated community is the home and grave of Samuel Johnston. He owned all of the land along the left edge of the bay, one of his three plantations. Born in Scotland in 1733, Johnston was brought to North Carolina as a toddler, when his father got a colonial post through his brother, the royal governor. A Yale dropout, Johnston studied law with local attorney Thomas Barker, Penelope’s husband, and passed the bar in 1756.

Three years later he was elected to the Provincial Assembly, and served until that body collapsed with the flight of the royal governor from New Bern in 1775. A strong supporter of the revolution and member of the committee of safety, Johnston nonetheless took in the Polloks after Cullen’s torture and was known to oppose personal violence against Loyalists.[19] Early in the war he served in the initial Provincial Congresses (predecessors of the modern General Assembly), facilitating the last two as president. Later he was in the Continental Congress, but turned down the first presidency of the United States under the Articles of the Confederation that preceded the Constitution. He returned home.

After the war he was a lawyer, president of the state conventions to ratify the U.S. Constitution, governor for two terms, a U.S. senator, and a judge, before retiring at age 70. He lived at the house here, “Hayes,” until dying at 83.

Homes of Rebellion

Walk to the right down Water Street, noticing the 1773 Homestead House across the street. Then take the next left, Broad Street. Walk to what now is the Edenton Welcome Center, the two-story house on the left.

Walk to the right down Water Street, noticing the 1773 Homestead House across the street. Then take the next left, Broad Street. Walk to what now is the Edenton Welcome Center, the two-story house on the left.

Built in 1762 two blocks north of here (up Broad Street), the original part of the house runs from the area of the current doorway to the right end. That was the home of Penelope Barker, organizer of the Edenton Tea Party.[20] She was born Penelope Padgett in Chowan County and inherited her way to extreme wealth, first from her father and then from two rich husbands who died. She was already well off when her second husband Thomas “left Penelope all his property, which included town lots, two plantations, 33 mahogany chairs, 53 slaves, watches, horses and 400 books.”[21]

Go in the Welcome Center if open. When you get upstairs, notice the fireplace mantle attached to the wall on the right.

The ladies of the Tea Party did their work in front of this mantle, taken from the King home when it was demolished. Above it is a drawing of the house pieced together from the memories of people who had seen it.

While at the center you may want to take in the exhibits, including one on Barker, and inquire about tours of our next stop, the Cupola House.

Exit the center and cross to the far side of the Broad Street loop. Turn right, and cross Water Street. Stop at the Cupola House on the left.

Exit the center and cross to the far side of the Broad Street loop. Turn right, and cross Water Street. Stop at the Cupola House on the left.

Cupola House was built in 1758 by a man who helped cause the War of Regulation before the Revolution. Francis Corbin set up the system by which a large portion of North Carolina was sold off in lots from the owner recognized by England, nobleman Lord Granville. Corbin personally arranged sale of the tract for which the Wachovia Tour is named, including all of today’s Winston-Salem. Moravian Bishop Augustus Spangenberg and his survey party came from Pennsylvania to meet Corbin in August 1752, before exploring what now is northwestern N.C. and choosing that tract.[22]

Corbin’s methods, and those of various land agents working for him, were considered corrupt by people in the western part of the colony. He died in 1768 around the start of organized protests and violence against them by the Regulators.

For a while this was a rental house, until bought in 1777 for £400 by Dr. Samuel Dickinson (a bargain at $71,000 in modern dollars).[23] Dickinson was a busy man, part of the local government in addition to his medical practice and shipping investments. And that was a big year for him. He was elected justice of the peace and bought the house, because he had just married the niece and namesake of Penelope Barker, Elizabeth Penelope Eelbeck Ormand. Wealthy herself by inheritance from her father and a prior marriage, Elizabeth signed the Edenton Tea Party petition three years earlier.

Dr. Dickinson was only 59 when he died in the house in 1802 of a fever. Elizabeth survived him by 17 years, dying at 69.

Continue up Broad Street. At King Street, look diagonally across the intersection to the northeast corner. You will see a tiny marble rectangle in the wall of the building there, on the King side. It notes that the office of Joseph Hewes, mentioned twice earlier, was on that corner.

Turn left and walk to 105 W. King on the left, which is privately owned.

Turn left and walk to 105 W. King on the left, which is privately owned.

During the war this house is owned by Hewes, probably as a rental property. It’s unclear where Hewes lived,[24] but he was a successful merchant and shipowner. He served in the Provincial Congress and then was elected to represent the province at the pre-war Continental Congress. In 1776 he wrote a letter from Philadelphia to the Provincial Congress asking how to vote on the question of independence. The response was the Halifax Resolves, the first open endorsement of independence from England by an American colony. He read it to the Continental Congress, but hesitated in his support.

Founding Father and later U.S. president John Adams wrote that one day in June 1776, a member of the Congress was reading documents proving each colony supported independence. Hewes was considered the key to gaining a majority vote. After the member read those from N.C., Hewes “‘started suddenly upright and lifting up both his hands to Heaven, as if he had been in a trance, cried out, “it is done, I will abide by it.’’” He voted for and signed the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Hewes left the Quaker church over the war—and perhaps his love of dancing![iii]

Hewes chaired the new country’s Naval Committee, and recruited one of the most famous navy heroes in American history, John Paul Jones. He also gave his merchant fleet over to the Congress for refitting as warships. He is buried in the same cemetery as Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia.

Walking a Thin Line

You can go straight up Broad Street to Church Street. But to see the currently private homes of Capt. Borritz and Tea Party petition signers, continue down King to South Granville Street. Turn right and immediately left onto Blount Street. The 1772 Borritz house is about halfway down on the right, at 108. The next paragraph is not on the audio recordings.

In 1776 the Continental Congress paid for a sculpture to honor Gen. Richard Montgomery, killed the year before in a failed invasion of Quebec. When completed by a French sculptor, Congress had not yet chosen a capital city, so Benjamin Franklin—a close friend of Joseph Hewes—paid to have it shipped here for safekeeping. This first national monument was likely stored here when this was the Customs House during the Revolution, where taxes were collected on imported goods. After New York was named the first capital, the monument was shipped there in 1787, and it now sits outside historic Trinity Church.[iv]

Return to South Granville, turn left, walk one block, and turn left again. Abigail Charlton and her attorney husband lived at 206 West Eden Street, built in 1765. Return to Granville, go up another block, and turn right. Lydia Bennett lived in the 1757 house at 120 West Queen Street. Continue to Broad Street and turn left. Walk two blocks.

Cross Church Street to visit St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. Before the war it was an Anglican church.

This building was begun in 1738, the third home of North Carolina’s oldest church congregation, founded in 1701. All of the colonial residents you’ve read about here likely attended, given that the Anglican Church was the official church of Great Britain. The building was not completely finished until 1774, not counting the bell tower raised in 1806.[25]

This building was begun in 1738, the third home of North Carolina’s oldest church congregation, founded in 1701. All of the colonial residents you’ve read about here likely attended, given that the Anglican Church was the official church of Great Britain. The building was not completely finished until 1774, not counting the bell tower raised in 1806.[25]

Go inside if it is open.

The vestry—the council that ran the church—meets here on Monday, June 19, 1775, to add its opinion on the growing tensions… while also trying to walk a thin line. After all, King George III is the official head of the church! They draft a document here called “The Test” that opens by affirming loyalty to the king. But they also say, “‘we do absolutely believe that neither the Parliament of Great Britain nor any member of a constituent branch thereof, have a right to impose taxes upon these colonies to regulate the internal policy thereof; that all attempts by fraud or force to establish and exercise such claims and powers are violations of the peace and security of the people and ought to be resisted to the utmost…’” Therefore, they also say, they are bound to adhere to the laws of the Provincial (rebel) and Continental Congresses.[26]

A key issue in the argument between the colonies and Parliament was over the latter directly taxing colonists, who did not have representatives in that body. Earlier North Carolinians were only taxed by the colonial government, where they were represented in the Provincial Assembly.

After the war, Anglican churches in the new country formed their own governing body and changed their name to Episcopal, though many of their doctrines and ceremonies remained similar to the English church’s.

Our tour is done. If you have been walking, the historic site and your vehicle are across Broad Street.

Historical Tidbits

- A signer of both the Declaration of Independence (for Pennsylvania) and the U.S. Constitution died in the Iredell House in 1798. James Wilson, who was on the Supreme Court with Iredell, apparently sought refuge with his friend after a bad land deal left him with massive debts, and died after a few months.[f]

- One of the most compelling runaway slave stories in American history took place in Edenton. Born here in 1813, Harriet Jacobs escaped a sexually abusive master, hid in her grandmother’s attic for seven years, and eventually escaped by ship to New York. Her 1861 book is considered a vital slave narrative. (Learn more.)

More Information

- Bair, Anna Withers, ‘Johnston, Samuel’, NCpedia, 1988 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/johnston-samuel> [accessed 23 September 2020]

- Barefoot, Daniel, Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1998)

- Boyette, Charles, Historic Edenton State Historic Site, In-person interview with tour, 9/15/2020

- Cheeseman, Bruce, Historical Research Report: The Cupola House of Edenton, Chowan County, Vol. 1—Text (North Carolina Office of Archives and History, 1980) <https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll6/id/10971/rec/7> [accessed 20 May 2020]

- ‘Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina’, 2010 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/717/> [accessed 12 April 2020]

- Crow, Jeffrey J., The Black Experience in Revolutionary North Carolina (Raleigh, N.C.: Div. of Archives and History, N.C. Dept. of Cultural Resources, 1977)

- ‘Cupola House History’, The Cupola House <http://cupolahouse.org/history.php> [accessed 13 April 2020]

- Dillard, Richard, The Historic Tea Party of Edenton, October 25th, 1774, Fourth Edition, privately published, 1907

- Edenton Historical Association, “Barker House Facts”

- Finlay, Jennifer, Edenton History, In-person interview, 9/15/2020

- ‘Front View, Chowan County Courthouse, Edenton, Chowan County, North Carolina (Chowan County Courthouse (Edenton, N.C.)’, NC State University Libraries’ Rare and Unique Digital Collections <https://d.lib.ncsu.edu/collections/catalog/bh1095pnc001#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-3699%2C0%2C10979%2C5336> [accessed 13 April 2020]

- Ganyard, Robert L., The Emergence of North Carolina’s Revolutionary State Government, North Carolina in the American Revolution (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1978).

- Halsey, R. T. Haines, The Boston Port Bill as Pictured by a Contemporary London Cartoonist (New York, NY: The Grolier Club, 1904) <http://archive.org/details/bostonportbillas00halsrich> [accessed 24 June 2021]

- Higgenbotham, Don, ‘Iredell, James, Sr.’, NCpedia <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/iredell-james-sr> [accessed 17 April 2020]

- ‘James Iredell House’, Edenton Historical Commission <http://ehcnc.org/historic-places/iredell-house/> [accessed 17 April 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Edenton (#1)’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2009 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_edenton.html> [accessed 13 April 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Edenton (#2)’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2009 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_edenton.html> [accessed 13 April 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Edenton, North Carolina’, Carolana, 2007 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Towns/Edenton_NC.html> [accessed 13 April 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Samuel Johnston’, Governors of the State of North Carolina, 2007 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Governors/sjohnston.html> [accessed 23 September 2020]

- MacMillan, Laura, The North Carolina Portrait Index (Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press, 1963)

- ‘Marker: A-1’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=A-1> [accessed 13 April 2020]

- ‘Marker: A-9’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=A-9> [accessed 18 September 2020]

- ‘Marker: A-22’ <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=A-22> [accessed 12 April 2020]

- ‘Marker: A-72’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=A-72> [accessed 13 April 2020]

- McCorkle, L.A., Old Time Stories of the Old North State (Boston, Mass.: D.C. Heath & Co., Publishers, 1903), ECU Digital Collections <https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/16828> [accessed 29 March 2022]

- McRee, Griffith John, Life and Correspondence of James Iredell: One of the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States, Vol. I (New York: Appleton, 1857)

- ‘Museum Trail’, Edenton Historical Commission <http://ehcnc.org/historic-places/museum-trail/> [accessed 13 April 2020]

- Nye, Eric, ‘Currency Converter, Pounds Sterling to Dollars, 1264 to Present’ https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm

- Parramore, Dr. Thomas, Cradle of the Colony: The History of Chowan County and Edenton, North Carolina (Edenton Chamber of Commerce, 1967), Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library.

- ‘Penelope Barker’, National Women’s History Museum <https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/penelope-barker> [accessed 12 April 2020]

- Powell, William, North Carolina: A History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988)

- ‘Queen, Louise, ‘Spangenberg, Augustus Gottlieb’, NCpedia, 1994 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/spangenberg-augustus> [accessed 29 September 2020]

- Rankin, Hugh F., The North Carolina Continentals (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1971)

- RS#10: The Edenton “Tea Party” (Transcript)’ (Baltimore County History Labs Program) <https://www.umbc.edu/che/tahlessons/pdf/historylabs/Should_the_Colo_student:RS10.pdf> [accessed 12 April 2020]

- ‘Stories of the American South: The Edenton Tea Party’, University of North Carolina Libraries <http://wayback.archive-it.org/org-679/20151013172029/http://library.unc.edu/shareheader/> [accessed 13 April 2020]

- The Historic Tea Party, Oct. 25, 1774, Special Exposition Edition (1907), State Library of North Carolina, Government and Heritage Library

- Thomas, Reid, ‘Discovery of the Oldest Dated House in North Carolina’, Edenton Historical Commission, 2013 <http://ehcnc.org/decorative-arts/southern-architecture/discovery-of-the-oldest-dated-house-in-north-carolina/> [accessed 18 September 2020]

[1] Boyette 2020.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Thomas 2013.

[4] NC State University Libraries’ Rare and Unique Digital Collections.

[5] Ganyard.

[6] Edenton Historical Commission (website).

[7] Cheeseman 1980.

[8] Crow 1977.

[9] Lewis 2007.

[10] Cheeseman.

[11] Finlay 2020; Boyette.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ganyard 1978.

[14] Lewis 2009 (Edenton #1).

[15] Nye.

[16] Lewis 2009 (Edenton #2).

[17] Angley, Wilson, A History of Fort Johnston on the Lower Cape Fear (Southport, N.C.: Southport Historical Society, 1996).

[18] Finlay.

[19] Ganyard.

[20] Edenton Historical Commission (“Barker House Facts”).

[21] Edenton Historical Commission (website).

[22] Queen 1994.

[23] Nye.

[24] Boyette.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Lewis 2007.

[a] Quoted in Halsey 1904, from the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, 1775.

[b] Quoted in Rankin 1971.

[c] Year and quotation from an 1827 newspaper article quoted in: Davis, Curtis Carroll, ‘Another Echo of the Tea Party’ (The State, March 1982, Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library, Vertical Files, “Edenton-History Tea Party #1”). Dillard (1907) says the glass picture was destroyed during the Civil War. But a 20th-Century source, exact year unlisted, says the remains were stored in a bank vault at the time it was written (Webb, James, ‘Noted Women of Edenton’ [Hillsboro, N.C.], Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library, Edenton – History, Tea Party #2).

[d] Modern sources attribute the panic to the Cornwallis rumors discussed later. But separate letters around April 22 to Hannah Iredell in Edenton, from her sister in Bertie County to the west and her husband James, Sr., elsewhere, only talk about the Portsmouth troops (quoted in McRee 1857). Her sister writes again on May 3 about the Cornwallis raid rumor, downplaying it. Windsor is southwest of Edenton and thus seems an unlikely place to hide if the triggering threat was Cornwallis, since Wilmington is farther southwest.

[e] Quoted in: Parramore 1967.

[f] ‘Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings: Iredell House, North Carolina’, National Park Service – Signers of the Declaration (Iredell House) <https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/declaration/site35.htm> [accessed 28 October 2024].

[i] A lay historian in Sweden uncovered primary documentation proving Borritz’s correct name and nationality, and that Borritz lived in Edenton. He also tied the errors to an 1847 publication. AmRevNC is grateful to Roland Blomstrand for providing this evidence (Blomstrand, Roland, ‘William and John Borritz,’ received 3/6/2024).

[ii] ‘Minutes of the North Carolina House of Commons, North Carolina. General Assembly April 19, 1784 – June 03, 1784 Volume 19, Pages 489-716’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1784 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr19-0006> [accessed 19 March 2024]; ‘Minutes of the North Carolina Senate North Carolina. General Assembly, April 18, 1783 – May 17, 1783, Volume 19, Pages 129-232’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1783 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr19-0002#p19-130> [accessed 19 March 2024]; ‘Minutes of the North Carolina Senate North Carolina. General Assembly, October 25, 1784 – November 26, 1784 Volume 19, Pages 400-488’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1784 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr19-0005> [accessed 19 March 2024].

[iii] In addition to other sources listed above: ‘Delegate Discussions: Benjamin Rush’s Characters’, 2016 <https://declaration.fas.harvard.edu/blog/dd-rush> [accessed 23 August 2024]; Francis, Mike, ‘Joseph Hewes of North Carolina, Signer of the Declaration of Independence’, The Oregonian/OregonLive, 2012 <https://www.oregonlive.com/oregonatwar/2012/07/joseph_hewes_of_north_carolina.html> [accessed 23 August 2024]; ‘Joseph Hewes | Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence’ <https://www.dsdi1776.com/signer/joseph-hewes/> [accessed 23 August 2024].

[iv] Starnes, Ritchie, ‘Franklin, Hewes Hid First Monument’, The Chowan Herald, 11 May 2011, Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library, Edenton – History, Revolution; ‘The General and The Monument’, Trinity Church Wall Street, 2011 <https://trinitywallstreet.org/stories-news/general-and-monument> [accessed 21 August 2024].