Dramatic Protests and British Occupiers

Context

Founded by 1739, Wilmington was the largest city and port in North Carolina during the American Revolution, with 1,200 residents and 200 homes.

Founded by 1739, Wilmington was the largest city and port in North Carolina during the American Revolution, with 1,200 residents and 200 homes.

Situation

A lot happened in Wilmington during the war, but this page emphasizes four events, listed here earliest to last:

- Rebellion—Rebellious political actions occurring over a 10-year period before the war.

- Warships—An attempt by British warships to get upriver past the town in 1776, to open the way to Loyalist-leaning Cross Creek (modern Fayetteville).

- Craig—Occupation by a corps under British Maj. James Craig for most of 1781.

- Cornwallis—A two-week stay by the battered army of British Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis after its costly “victory” at the Battle of Guilford Court House in today’s Greensboro.

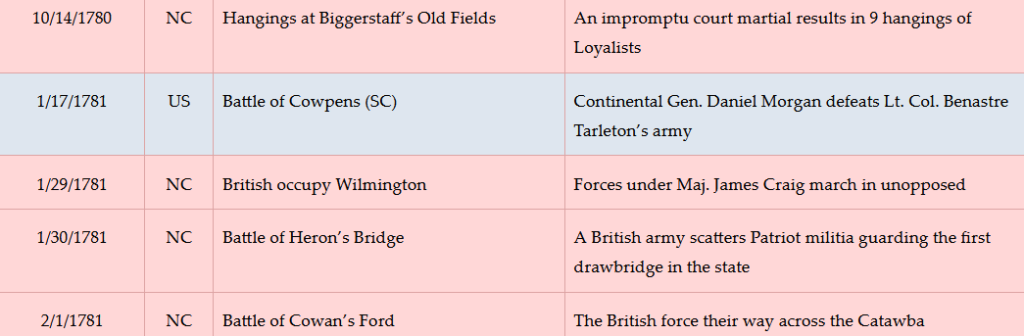

Dates

Saturday, October 19, 1765–Sunday, November 18, 1781.

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

The Courthouse

Go to and look into the intersection of Market Street and Front Street.

Rebellion: Before and during the war, the county courthouse is in the middle of this intersection. It is probably a log building, raised above head height on brick pillars. A farmers’ market is underneath. Above it is a simple tower with a bell.

Rebellion: Before and during the war, the county courthouse is in the middle of this intersection. It is probably a log building, raised above head height on brick pillars. A farmers’ market is underneath. Above it is a simple tower with a bell.

Early resistance to British policies occurred here, according to the North Carolina Gazette newspaper of November 20, 1765[1]:

- Around 7 p.m. on Saturday, October 19, almost 500 people—a large percentage of the population—gather here. They hang an effigy of a failed former prime minister, Lord Bute, who remains a hated advisor to King George III and supports the Stamp Act, a tax on paper goods. They then burn the effigy in tar barrels. Next they go to all the homes and force the men not already with them to come out and drink to “LIBERTY, PROPERTY, AND NO STAMP TAX,” followed by “three huzzas” after each. They disperse around midnight.

- The royal tax collector in North Carolina, William Houston, shows up in town on November 16 on personal business. Like all Sundays it is a market day, and a crowd of 300–400 gathers. Drums beat, flags wave, the bell is rung, and Houston is brought here to the courthouse. The crowd demands to know if Houston is going to enforce the Stamp Act. His slippery answer would make modern politicians proud. He says he “‘should be very sorry to execute any Office disagreeable to the People of the Province.’”[2] They take him inside, where he resigns his office. His exit is more pleasant. The crowd carries him to each corner here in an armchair, giving him three huzzas at each, then further around town, and finally to his lodging.

Thus it is fitting that protesters from across the region meet in the courthouse nine years later, on Thursday, July 21, 1774, in the first attempt to organize resistance in N.C. to a new set of British laws.[3] Called the “Coercive” or “Intolerable” acts, these are meant to punish Boston for the Boston Tea Party and other protests. The delegates decide to send a letter to other counties, calling for representatives to a convention that would elect delegates to the First Continental Congress.[4] They proclaim “the cause of the Town of Boston as the common cause of British America and as suffering in defence of the Rights of the Colonies in general.”[5] In November, local leaders meet at the courthouse as the “Wilmington Committee of Safety” for the first time, to coordinate area responses to Parliament.

A year later an open declaration of resistance is written or copied inside—details are fuzzy, including why this happened in Wilmington! On Tuesday, June 20, 1775, a small group from the Cross Creek area (now Fayetteville) create a document here later called the “Liberty Point Resolves.” The men pledge to defend their rights against “every foe” and support the Continental and Provincial congresses, the latter being the new rebel legislature. Eventually 55 property owners sign the Resolves in Cross Creek.

Most likely at the courthouse the next month, the committee of safety, now in effect the Patriot replacement for the local royal government, takes an action against liberty. It orders that all Africans and African-Americans, free or enslaved, be disarmed, and creates patrols to enforce the order. Slaveholders were terrified of slave rebellions.

The committee also takes harsh steps to enforce support for the growing cause of revolution. A Scottish visitor in 1775, Janet Schaw, reports that the committee’s supporters threaten “‘if you refuse, we are directly to cut up your corn, shoot your pigs, burn your houses, seize your (slaves) and perhaps tar and feather yourself.’”

She provides a vivid description of Wilmington at the time: “The people in town live decently, and tho’ their houses are not spacious, they are in general very commodious and well furnished… This town lies low, but is not disagreeable. There is at each end of it an ascent, which is dignified with the title of the hills; on them are some very good houses and there almost all my acquaintances are.” Still, it wasn’t her hometown of Edinburgh. She describes going to a ball “dressed out in all my British airs with a high head and a hoop (skirt) and trudging thro’ the unpaved streets in embroidered shoes by the light of a (lantern) carried by” an enslaved woman in rags.[6]

Drama by the River

Walk toward the river on either side of Market to the near side of Water Street, the last road before the river. From that corner, look into Market.

At the time, the river bank started here. You are standing on a narrow dock extending along this side of today’s Market and into the river. Another narrow dock extends from the middle, and a third is on the far side, creating two slips of water. These are used for smaller boats; a larger single slip is in modern Dock Street (a block to the left when facing the river). Larger ocean-going ships, all sailing ships in the 1700s, cannot maneuver into the river due to the winds and a shoal above Brunswick Town. So large rowboats are often used to ferry goods to and from them. Perhaps one is near you, unloading goods into warehouses lining the dock and street behind you, while logs and barrels of tar are being loaded into the other for shipment. At the start of the war, Wilmington was one of the leading exporters in the world for these shipbuilding materials, and the British Navy was dependent on it prior to the Revolution.[7]

At the time, the river bank started here. You are standing on a narrow dock extending along this side of today’s Market and into the river. Another narrow dock extends from the middle, and a third is on the far side, creating two slips of water. These are used for smaller boats; a larger single slip is in modern Dock Street (a block to the left when facing the river). Larger ocean-going ships, all sailing ships in the 1700s, cannot maneuver into the river due to the winds and a shoal above Brunswick Town. So large rowboats are often used to ferry goods to and from them. Perhaps one is near you, unloading goods into warehouses lining the dock and street behind you, while logs and barrels of tar are being loaded into the other for shipment. At the start of the war, Wilmington was one of the leading exporters in the world for these shipbuilding materials, and the British Navy was dependent on it prior to the Revolution.[7]

However, the slips may well be empty instead. The British navy, and quasi-legal pirates called “privateers” supporting them, partially blockaded the Cape Fear starting in 1777.

Cross Water to the fence at the river overlook. During the war, you would be in the river. Look left (downriver).

Warships: Imagine you are shivering in a small boat on the river on Sunday, January 28, 1776. Wilmington is in an uproar, having learned two small British warships are approaching the town from the ocean, after a brief attempt to retake Ft. Johnston at the mouth of the river (today’s Southport). “Martial law was in effect, and all those who refused to take an oath to support the patriot cause were forced to work on the fortifications. Twenty professed Loyalists were taken into custody. Guns were mounted on the parapets; fire rafts were prepared; stores removed; and the women and children were sent to safety outside the town.”[8]

Royal Gov. Josiah Martin, forced to flee New Bern the previous summer, is aboard one of the ships, the HMS Cruizer. He has been living on it ever since. Now he is trying to get past Wilmington to Cross Creek, where a Loyalist army of volunteers is forming. On your side of the river, though, are formidable breastworks—ridges of dirt—with cannons facing downriver, manned by Patriot militia (part-time soldiers). The ships draw off and try to go around Eagle Island, which you can see directly across the river. The Brunswick River runs along its far side and feeds into the main channel of the Cape Fear, so they would have come out upriver of the island.

The water is too shallow[9], though, so the ships reappear later in the day. In the far distance, out of range of the Patriot (or “Whig”) artillery, you see rowboats being lowered over the sides and British troops getting into them to raid the town. Patriot militia begin shooting at them from both sides of the river, so the exposed British give up. The troops and boats go back onboard, and the ships retire.

Sorrows and a Sniper

Walk up Water Street (to the right when facing the river). Stop at the broad steps on the right at the back of the federal courthouse, and go up them if you wish. Look across the river at the U.S.S. Wilmington. It rests in the continuation of the Cape Fear River. The water to your right is the North Cape Fear River. The land between the two, on the other side of the Cape Fear from the battleship, now is called Point Peter, for Peter Mallet, who owned it in the 1700s.[10]

The point had pens for holding enslaved people before and after sales in Wilmington, if bound for elsewhere, according to the National Park Service. Separation from enslaved and free blacks in Wilmington reduced the chances of people escaping, as did the tragic practice of holding newly separated family members in different places. During the Revolution the area was called Negro Head Point, because the head of an executed man was supposedly displayed there as a warning to other slaves, but there is no evidence for that story.[i]

The point had pens for holding enslaved people before and after sales in Wilmington, if bound for elsewhere, according to the National Park Service. Separation from enslaved and free blacks in Wilmington reduced the chances of people escaping, as did the tragic practice of holding newly separated family members in different places. During the Revolution the area was called Negro Head Point, because the head of an executed man was supposedly displayed there as a warning to other slaves, but there is no evidence for that story.[i]

In March 1781, some of Maj. Craig’s British troops massacred eight patriots at Rouse’s Tavern eight miles northeast of town, in today’s Ogden. A related story comes entirely from the son of a Revolutionary War soldier who collected memories from veterans years later. The star of the story, later a well-known politician, never wrote about it, nor are these events mentioned in British records.[11] However, the author said he knew the son in the story well in later years, and the third man is identified in unrelated records. Still, believe with caution!

Craig: According to this story, Patriot militia leader Lt. Col. Thomas Bloodworth[12] wanted revenge for the massacre, especially since one of those killed was a friend. One day while fox hunting, Bloodworth discovered a huge, hollow cypress tree on Point Peter. A gunsmith, Bloodworth made a long-range rifle and practiced shooting at a human figure drawn on his barn from the distance between here and the point. In July he canoed to the Point with his son Timothy and an employee, Jim Paget, with provisions and his rifle. They built a platform inside the tree and bored holes with a hand-drill for air and for shooting.

On Wednesday morning, July 4th, 1781, some British soldiers are gathered at “’Nelson’s liquor store’” here or nearby. Suddenly one of the soldiers falls backward, followed by the sound of the gunshot. He is dragged into the store as a second soldier is dropped, followed again by the gun’s report. No doubt they scatter, but yet another man is hit.

A former member of the U.S. Army Special Forces who became a Revolutionary War re-enactor comments, “This would have been a tough shot, but not an impossible one. In today’s army every soldier must be able to hit a target at 400 yards with (normal) sights. With the weapons of the 18th Century it could be done.”[ii]

Boats are launched to scour the opposite river bank. None go as far as Point Peter, since a shot from that distance seems impossible. Around noon the next day, the shooting starts again. One cavalryman rides to the Market Street dock to water his horse and is knocked off of it.

This supposedly goes on for almost a week. Then a Tory visitor tells the British that Bloodworth is missing, that he saw him going somewhere with a big gun, and that the point was his likely destination. A unit is sent there and finds the empty tree, but too late in the day to cut it down. Bloodworth’s group is hiding. As the British camp overnight, the Patriots capture and tie up a Redcoat guard near their canoe and escape.

Prisons and Patriots

Walk back to the near side of Market, turn left, and go up past Front to Second Street.

Cornwallis/Craig: Where a parking lot now lies across Market Street, a rectangular wooden building you see from one end is used as an army hospital during the British occupation. Among its patients would have been some of the wounded from Guilford Court House. Those too weak to walk were floated across the Cape Fear by boat over the two days before the main army’s arrival, described below.

Cornwallis/Craig: Where a parking lot now lies across Market Street, a rectangular wooden building you see from one end is used as an army hospital during the British occupation. Among its patients would have been some of the wounded from Guilford Court House. Those too weak to walk were floated across the Cape Fear by boat over the two days before the main army’s arrival, described below.

Cross Second and stop on the corner by the bank.

Craig: Here or perhaps a little farther along 2nd stands a place of misery during Craig’s time. In a low spot in the ground now covered by the modern bank building was a corral of sorts, a high fence of rails with no roof. Called the “Bull Pen,” Craig keeps captured Patriots here, exposed to the sun and rain.

Perhaps you see, through the slats, John Ashe huddled in a corner, shivering and covered in sores. Ashe had been a member of the Provincial Assembly, the colonial legislature, but became a leader of the Stamp Act protests in the 1760s. A Patriot officer at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge, which ended Gov. Martin’s hopes of reclaiming the colony in 1776, he was appointed a brigadier general in the state militia later that year. When the British arrived, he went into hiding, but was betrayed and imprisoned here. During a long stay he got smallpox. Finally released due to the illness, he died on the way to his family in Hillsborough.

Another victim of the Bull Pen was political leader Cornelius Harnett, described below at his grave.

Continue another block until you are across from the Burgwin-Wright House at Third Street, and look farther up Market.

Rebellion: During the war, you just walked the entire width of Wilmington proper, though homes are scattered throughout a larger area. The town only goes one more block to the left (to Chestnut Street) and two to the right where Orange is today, though there is no street there yet!

Around 3 p.m. on Wednesday, May 8, 1775, a rider gallops into town from ahead of you, down the dirt road from New Bern that becomes Market Street at this intersection. He likely continues down to the courthouse. He announces that American militia fired on British troops in Lexington and Concord, Mass., on April 19. It has taken exactly two weeks for the news to get here, by horseback, of the first military action of the American Revolution.

Look left up 3rd Street.

Cornwallis: Cornwallis’ army arrives here from Guilford Court House over two days starting Wednesday, April 11, 1781. The army marches in along 3rd Street and eventually into the encampment past modern Orange Street. There his 1,700 men including 225 N.C. Loyalists, plus camp followers and people escaping slavery, crowd into Craig’s fortifications. A letter Cornwallis writes three days later, to his commander Sir Henry Clinton in New York City, both explains his decision and describes the men you see: “‘With a third of my Army Sick & Wounded which I was obliged to carry in Waggons (sic) or on horseback, the remainder without shoes & worn down with fatigue, I thought it was time to look for some place of rest & refreshment.’”[13]

With them are “Hessian” mercenaries who fought alongside the Redcoats at Guilford. “A German soldier in the Von Bose Regiment recalled that they received double rations of rum each day and plenty of provisions of meat and ship’s bread (also called “hardtack,” long-lasting and cracker-like). Shoes, shirts, and breeches were replaced, welcome changes for the men in worn out clothing.”[14]

Meanwhile, Cornwallis writes an officer friend, “Now, my dear friend, what is our plan?”[15] As his army heals, he debates at least eight different options, according to his letters.[a] Eventually he decides—against late-arriving orders from Clinton—to move to Virginia. He hopes to join up with another British army there. Just two weeks after arriving here, they pack up camp, drums roll, columns form, and Cornwallis’ army marches back out 3rd Street to its eventual surrender at Yorktown.

The impact of his North Carolina campaign on that army shows in his “returns,” or troop counts. He entered the state in January with 3,224. He leaves three months later with half that number—1,723.[16] Craig’s force remains behind, to keep the port open for supplies.

Cross Market to the Burgwin-Wright House.

Cornwallis: This home was built in 1770, atop the former county jail, for John Burgwin, the Royal Treasurer of the colony of North Carolina. This was intended only to be a showcase and guest home; he continued to live at his plantation “The Hermitage” in today’s Castle Hayne north of town, and use an older home near here as his “townhouse.”

An English immigrant at 19, Burgwin became a merchant and planter. He married into money, but his wife died before the war. Having served as the private secretary to previous royal governors, and also the register of deeds as war broke out, Burgwin was the highest-ranking British official in town. So he was probably a Loyalist.

A game of Blind Man’s Bluff turned out badly when Burgwin fell and broke his leg.[17] He must have decided this was a good excuse to get out of town—all the way to England, supposedly for treatment. Burgwin returned to N.C. a couple of times during the war, however. He rented out this home at the start of the war to the Wrights, who would later buy it. Among his other “properties” were as many as 200 forced laborers, including at least 10 enslaved at this house.

Cornwallis is entertained here at least one night: A local writes of seeing him come down the wooden front steps after a party.[18] The host is unknown, as records do not indicate whether any of the Wrights were here at the time, or whether officers were housed here.[19] Also unclear is where his headquarters were, though it was not here, contrary to a nearby monument. Other intriguing stories told about the house are also sadly untrue.[20]

Despite never openly declaring himself a Tory, Burgwin sought and received a pardon under the terms of the Treaty of Paris that ended the war, and returned with his English wife and children. They lived at his plantation and sold the house here, confiscated by the state like many Loyalist properties, after 10 years of petitioning to get it back.[21]

You can learn more of the home’s fascinating history, and stand where Cornwallis did, by touring the house.

A Walk through the Church

Cross Third Street, and continue up Market to the church graveyard at the corner with Fourth Street.

Rebellion: Like a ghost, you just walked through the wall of the original St. James Church! It ran from partly up the block to the far corner, and jutted out slightly into Market Street.[22] The church’s design proved too big for the lot that was donated, so the legislature agreed to let the grounds extend 30 feet into the street.[iii]

Rebellion: Like a ghost, you just walked through the wall of the original St. James Church! It ran from partly up the block to the far corner, and jutted out slightly into Market Street.[22] The church’s design proved too big for the lot that was donated, so the legislature agreed to let the grounds extend 30 feet into the street.[iii]

The Gazette issue quoted earlier tells of a bit of political theater in the older part of the cemetery up Fourth Street, during the 1765 Stamp Act protests. Another large group “‘produced an Effigy of LIBERTY, which they put into a Coffin, and marched in solemn procession with it to the Church-Yard…’” Acting as if to bury it, “‘they thought it advisable to check its pulse…’” Then they gave it a place of honor in an armchair before a bonfire amid “‘great Rejoicings, on finding that LIBERTY had still an Existence in the Colonies.’”[23]

Warships/Cornwallis: Some sources suggest earthworks were brought right up to the church by the Patriots in 1776. This seems possible given that at the time, it was part of the official Church of England, and the colonial pastor had resigned that year. Local traditions that the British desecrated it come from an 1843 church publication that doesn’t cite its sources. It claims, “The inclosure (sic) of the graveyard was removed and burnt, while the church itself was stripped of its pews and other furniture and converted, first into a hospital for the sick, then into a Block-house for defence against the Americans, and finally into a riding school for the Dragoons of Tarleton.”[24] Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton was Cornwallis’ cavalry commander.

Look at the sidewalk behind the fence, running from the church building on the right and turning right behind that.

Just past the sidewalk corner is the grave of Cornelius Harnett, an area merchant. Harnett was perhaps the key political leader of the American Revolution in North Carolina. A long-time member of the colonial and then state legislatures, he led area protests against the actions of Parliament. These included an armed march on Royal Gov. William Tryon’s home in Brunswick Town in 1766, and the burning of Fort Johnston 10 years later. He presided over the creation of the Halifax Resolves that declared N.C. support for independence, and was the first person to read the U.S. Declaration of Independence to the general public in the state.

Harnett was captured by Craig’s troops and supposedly carried to the Bull Pen across a horse like a sack of flour. He died from illness contracted there at age 58. His epitaph, which he wrote on his deathbed, suggests he was a Deist rather than a follower of formal religion: “Slave to no sect, he took no private road/ But looked through nature up to nature’s God.” Harnett County is named for him, and Harnett Street in Raleigh. Read more about him.

Fortifications on the Hill

Go back to Third Street and turn left. As you pass the back of the Burgwin-Wright complex, notice the next home on that side, the Boatwright House, at 14 S. Third Street. Built in the 1760s, it thus was here during the war.

Walk two blocks to Orange Street.

Warships: In 1776, you would have been near, or standing on top of, an earth breastwork built by Patriot militia. Others are two blocks past the other side of Market (today’s Chestnut, not a road then), along the river, and on the heights north and south of town, as far south as modern Greenfield Park.[25]

Warships: In 1776, you would have been near, or standing on top of, an earth breastwork built by Patriot militia. Others are two blocks past the other side of Market (today’s Chestnut, not a road then), along the river, and on the heights north and south of town, as far south as modern Greenfield Park.[25]

Craig: These are no barrier to Craig’s army of 300 regular British troops, mostly Scottish Lowlanders, as they arrive on Monday, January 29, 1781. They had sailed partway up the river from Charleston, landed at the Ellis Plantation about nine miles south, and marched the rest of the way using a road along the river. They are unopposed as they enter town, probably at Front Street; the local militia had only about 50 men under arms, so all have wisely left town.

Craig’s troops establish a fortified camp on the hilltop in front of you, then mostly empty with no streets. Over time, troops and escaped slaves from around the area build up a breastwork around the hill. According to an unsigned 1781 map of the camp, this is reinforced with large, sharpened wooden stakes called “abattis” jutting outward the entire length, in some cases two rows of them. The nearest section might be just on the other side of Orange, almost parallel to the street, though slowly angling into and across it to your left. The abattis point toward you. They probably turn right around today’s Fifth Street, run less than a block south, and then cut back to the river in a rough diagonal along the hilltop. (See the map toward the bottom of the page.)

The soldiers camp, or perhaps build barracks, within the earthworks. Many officers in Craig’s and Cornwallis’ armies are hosted in private homes all around town. In some cases this was easy because the pro-Revolution owners had fled. Also, some percentage of the population were Tories who had lived in uneasy peace with rebels and neutrals. Realizing supplies are scarce, Craig soon orders Patriot women and children out of town.

Still, by summer, a resident reports prices have gone up by 300%. At one point the town is down to a two-week supply of flour, and the British do not have enough food for its prisoners. Craig admits residents are suffering.[b]

Turn left and walk about halfway up the block along Orange Street. Be careful—don’t prick yourself on abattis as you climb over the breastwork!

Look across Orange into the church parking lot.

Possibly directly in front of you, at the highest point of the modern parking lot, is a raised platform with a few cannons taken from a ship, manned by sailors. Shaped like part of a circle, the arc is on this side so the cannons can spread their fire. The 1781 map shows there also are two triangular “sailor’s batteries” elsewhere along the earthworks plus four square “redoubts,” very small forts.

Craig is known to have two brass “three-pounders” (referring to the weight of ball they normally fire) and two iron six-pounders in addition to the naval cannons; some or all may be on the redoubts.

If you want to tour the camp, a 14-block walk, skip to the “Fortification Tour” section below. You will end up at the Field Headquarters described next.

The Occupation Ends

If you aren’t touring the fortifications, go back to 3rd Street and turn left. Walk one block to Ann Street, and turn right. Walk two blocks to the corner with Front Street.

The best candidate for the location of Craig’s headquarters is in today’s Front Street, more than halfway up the block to your left. It could be a building shown on a 1769 map of Wilmington,[26] or it may be a large round tent called a “marquee” with a small stockade around it. (The 1781 map shows a half-circle within a rectangle, but no physical description remains.) Regardless, this vicinity puts the headquarters roughly halfway between the British-occupied buildings in town and the back of the camp (see camp map below). Cornwallis could have used it as well.

The best candidate for the location of Craig’s headquarters is in today’s Front Street, more than halfway up the block to your left. It could be a building shown on a 1769 map of Wilmington,[26] or it may be a large round tent called a “marquee” with a small stockade around it. (The 1781 map shows a half-circle within a rectangle, but no physical description remains.) Regardless, this vicinity puts the headquarters roughly halfway between the British-occupied buildings in town and the back of the camp (see camp map below). Cornwallis could have used it as well.

The breastwork with abattis may cross Ann Street about halfway up the block from Front. It then is thought to take a hard right in Front below the headquarters, and line the top of the river bank back in this direction. (At the time, the sharp drop on the right continued up to the left.) Another redoubt is probably where now there is a multistory building down and across Front Street. The breastwork angles away from it along Front, leaving a gap. This might be used to create a protected entrance to the camp from town.

Turn right and walk one block to Orange Street. Look at the building on your right.

On the corner stands the 1740s Mitchell-Anderson House, much changed since the war. At that time it is owned by merchant Robert Hogg, part-owner of the largest salt importing business in the state.[27] Though there were some salt works and mines in the American colonies, the majority of this vital commodity had to be shipped in. The British blockade no doubt hurt business, so the state supported new salt works like those in Beaufort.

Continue along Front Street.

Rebellion: Somewhere along the right side of this block, barracks were constructed for some of the new Continental (regular American army) soldiers during the build-up to war. Also in town was a storehouse for ammunition, used to supply N.C. Continental forces through most of the Revolution.

Three regiments are formed and trained in town, starting in March of 1776. The troops mutiny on July 14, tired of being stuck here with inadequate supplies, and wanting to be in the action in the North. Militia, better armed at this point than regular troops, surround this and other barracks in town to bring them under control. By ironic coincidence, this is also the day a copy of the new U.S. Declaration of Independence arrives and is read in town for the first time.

After the Continental regiments participate in several southern campaigns that first year, returning here each time, they finally march north to join the army of Gen. George Washington on Monday, April 7, 1777.[28] When Craig invaded, some of his troops moved into the Continental barracks.

Go on to the near side of Dock Street and look across Front.

Craig: As noted earlier, during the war period a large slip is in the middle of today’s Dock Street, with wharves and warehouses on each side. Craig’s supply or “commissary” officers took over the warehouse that runs along the left wharf, the end of which you see from here in 1781. This location provides for easy transfers of supplies from the boats to the camp.

Walk another block back to Market Street.

By mid-November 1781, things are getting desperate for Craig. A Patriot militia army at least three times the size of his, under Brig. Gen. Griffith Rutherford, has been marching to attack him. Rutherford, who led the 1776 campaign against the Cherokees, is camped at Heron’s Bridge about nine miles north. Craig has only two-weeks’ worth of flour left, but he cannot send out foraging parties with Rutherford so close. The British are forced to let their horses roam Eagle Island to find their own food.[29]

Given the situation, perhaps Craig has mixed feelings when he receives word of Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown the month before, and his own orders to go back to Charleston. On Sunday, November 18, his troops form into a column in Market Street facing the river to the sound of fifes and drums. They and their baggage begin to load onto ships all along the wharves. As many as 1,000 Tory civilians from around the region have already fled to the British ships downriver, leaving most of their possessions behind.

The army is joined by camp followers and an unknown number of people escaping slavery. One of the escapees suffers tragic disappointment. Lavinia, held by Declaration signer William Hooper, is spotted by friends of his. They physically drag her back to Hooper’s house, near Princess Street between Second and Third.[30]

Cavalrymen Cause Confusion

Look right, up Market Street toward Third.

From the far distance up today’s Third Street, dust arises. Continental and militia cavalry turn the corner into Market.[c] Some of the British troops are still waiting to board. The Patriots begin hacking at the end of the column with their swords. (Cornwallis’ surrender did not end the war.)

From the far distance up today’s Third Street, dust arises. Continental and militia cavalry turn the corner into Market.[c] Some of the British troops are still waiting to board. The Patriots begin hacking at the end of the column with their swords. (Cornwallis’ surrender did not end the war.)

A man standing somewhere near the courthouse witnesses a gruesome act of revenge. A Tory lagged behind the column, not expecting any danger, and is clearly confused by the arrival of the cavalry. The fact that Continental cavalry wore green coats similar to those of the British cavalry may have played a role. When they approach, the man “‘in a state of apparent mental hallucination walked forth with his hand stretchd (sic) out, as if to salute the troop.’” One of the militia riders pulls his sword, rides toward the Tory, and “‘laid his head open, the divided parts falling on each shoulder.’”[31]

The British return scattered fire. Sources differ on whether the Patriot forces retreat before cannon on the ships can turn on them, or the cannons get off a round. One of the Redcoats is killed and an unknown number wounded, while two or three cavalrymen are wounded. The last of the British speed aboard, and the ships sail away. Thus ends what is by far the longest British occupation of any town in North Carolina during the American Revolution.

Soon after, Rutherford’s army arrives down Third from Heron’s Bridge and has to restore order: Local Patriots have been attacking the few remaining Loyalists, taking out their frustrations after most of a year under British military rule.

Whigs and Tories continued to target each other across the state for months to come, and the British make one more appearance in 1782. But large-scale combat in the state comes to an end, seven years after it started with an attack on Fort Johnston launched from here.

Fortifications Tour

You can circle the British camp, and see possible locations of its features, as shown on the 1781 map. The camp map below is an “educated best guess” of those locations relative to modern streets.[32] For ease of reading, the section is written as if this map is accurate, but believe with caution!

From the sailor’s battery on Orange, continue up Orange across Fourth Street. As you take this tour, remember that none of these streets existed at the time.

About halfway up the block, back a bit from the street around 418 Orange, is one of the small square redoubts. The cannons faced east, the direction you have been walking, to protect against attack from that side. As you continue to Fifth Street, you will pass by it and over the breastwork to the outside of the camp.

Go to Fifth Street and turn right. Walk toward Ann Street.

Again halfway down the block, the breastwork and abattis on your right turn back toward the river, continuing in a straight, diagonal line all the way to Fourth Street. (Where the abattis or breastwork are mentioned below, remember the other is there, too.)

Turn right at Ann, and walk to Fourth Street. You cross the breastwork again and re-enter the camp about halfway down the block, which angles across the road. Turn left, cross Ann Street (not Fourth yet), and walk to where the sidewalk curves.

Around this point the breastwork turned slightly left away from the current sidewalk, to curve around a triangular sailor’s battery across today’s Fourth Street. Its near corner was almost directly across the street. The forward point of the battery faced southeast. (You were walking south, so southeast is toward your left.) One or several cannons are on each outward-facing side. Next the breastwork made a long curve, passing near the intersection ahead of you and out of sight past the battery.

Continue to, and turn right on, Nun Street. Walk halfway down the block.

The southwest corner of the battery is to your right. Off it begins a line of housing the 1781 map calls “quarters.” On that map, these are drawn as a line of small squares. Whether these refer to tents—which Craig probably had, but Cornwallis didn’t—or crude huts, or actual barracks built by Craig’s men, is unknown. Regardless, they run behind the houses to your right, slowly angling away from them and then crossing modern Third Street.

You are standing partway into a narrow ravine, drained by a creek that runs downhill to the river. The battery and nearby quarters, labeled as belonging to the “Light Corps,” are on the near side of the hilltop. A “light corps” was made up of fitter men trained to move fast, serving as scouts, a screen to protect the main army, and a rapid-strike force.

Continue to Third Street, and turn left without crossing it. Walk half a block.

You have crossed the valley and are standing in a square redoubt angled to face southeast. Across today’s street is the east end of the “Grenadiers quarters,” which parallels the Light Corps quarters across the valley. Grenadiers, originally larger soldiers capable of throwing the grenades of the 1600s, had evolved into elite attack units by the Revolutionary era. Off its far end begins the quarters for the Marines.

The abattis angle across Third just short of the modern intersection, so you will cross and re-cross them as you turn the corner.

Go to Church Street and turn right. Walk one block to Second Street. Turn left without crossing that, and walk down the block.

Just past today’s Craig Alley on the left, the breastwork catches up to you again. It takes a turn in the direction you are walking to get around the last, triangular, sailor’s battery, which again points southeast. The battery’s east corner is across the street from the alley. The breastwork angles across until it gets around 518 Second Street. There it takes a sharp right turn and runs straight toward the river for most of that block.

Continue to Castle Street, and turn right. Walk two blocks to Surry Street.

As you walk, the abattis move toward you again from the right. They cross Front Street at a slight angle just this side of the modern apartment high-rise, and continue into Castle directly in front of it. On the high ground occupied by that building, overlooking Surry Street, is another redoubt. This one provides protection from a Patriot approach along the river, or on the river road Craig’s force used. The river was closer to these heights than it is now, so the breastwork ends somewhere on the near side of today’s Dram Tree Park at the 1781 water’s edge.

Turn right on Surry, and then right again on Church, to return to Front Street. Turn left and walk a block to cross Nun. Stop about halfway down the next block. You may well be standing in Craig’s “Head quarters” per the 1781 map. Continue to Ann Street and face Front.

Return to the previous section, “The Occupation Ends.”

Historical Tidbits

- Only after peace negotiations were under way in Paris did the commander of the Southern Continental Army, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, make an appearance in Wilmington. On his way home to Rhode Island from Charleston by carriage, he arrived on Friday, August 22, 1783, and left two days later. While in town, he was honored by bonfires in the streets, the firing of guns, and illumination of houses in the evenings.[iv]

- As president, George Washington spent the night in Wilmington during his 1791 tour of the southern states. He came down what now is US 17 into Market Street and spent the night at a home on the southeast corner of Dock and Front streets (a small monument marks the location). He had dinner with town officials at a tavern where now sits the parking garage between Front and Second streets north of Market.[33]

More Information

- Barefoot, Daniel, Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1998)

- Butler, Lindley, North Carolina and the Coming of the Revolution, 1763-1776 (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1976)

- Butler, Lindley, and John Hairr, ‘Wilmington Campaign of 1781’, NCpedia, 2006 <https://www.ncpedia.org/wilmington-campaign-1781> [accessed 17 January 2020]

- ‘Black Soldiers in Red, Blue and Grey’, Cape Fear Historical Institute, 2006 <http://www.cfhi.net/BlackSoldiersinRedBlueandGrey.php> [accessed 11 May 2020]

- De Van Massey, Gregory, ‘The British Expedition to Wilmington, North Carolina, January-November, 1781’ (unpublished Master’s, East Carolina University, 1987)

- Drane, Robert Brent, Historical Notices of St. James’ Parish, Wilmington, North Carolina (Philadelphia, Pa.: R. S. H. George, 1843) <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/nc01.ark:/13960/t0pr91h3k>

- Dunkerly, Robert M., Redcoats on the Cape Fear: The Revolutionary War in Southeastern North Carolina, Revised (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2012)

- Dunkerly, Robert M., ‘Overlooked Wilmington’, Journal of the American Revolution, 2014 <https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/01/overlooked-wilmington/> [accessed 17 January 2020]

- Fonvielle, Chris, ‘With Such Great Alacrity’, North Carolina Historical Review, XCIV.2 (2017)

- Ganyard, Robert L., The Emergence of North Carolina’s Revolutionary State Government, North Carolina in the American Revolution (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1978)

- Hall, Wes, ‘An Underwater Archaeological Survey of Heron’s Colonial Bridge Crossing Site over the Northeast Cape Fear River near Castle Hayne, North Carolina’ (East Carolina University, 1992)

- Hooper, et al., William, ‘Resolutions by Inhabitants of the Wilmington District Concerning Resistance to Parliamentary Taxation and the Provincial Congress of North Carolina’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1774 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr09-0285> [accessed 11 September 2020]

- Howell, Andrew, The Book of Wilmington, 1959, Sampson County Public Library

- Ingram, Christine, Burgwin-Wright House, In-person interview with tour, 10/7/2020

- Ingram, Hunter, ‘The House Built on Wilmington’s First Jail’, Cape Fear Unearthed <https://omny.fm/shows/cape-fear-unearthed/the-house-built-on-wilmingtons-first-jail> [accessed 6 August 2020]

- Lamberton, Christine, Burgwin-Wright House, Phone interview, 11/3/2020

- Lee, Henry, Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States, Second Edition (Washington, D.C.: Peter Force, 1827), Google-Books-ID: DpwBAAAAMAAJ

- Lee, Lawrence, The Cape Fear in Colonial Days (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1965)

- Lewis, J. D., ‘The Evacuation of Wilmington’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2012 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_evacuation_of_wilmington.html> [accessed 17 January 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Wilmington’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2011 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_wilmington_2.html> [accessed 17 January 2020]

- Lossing, Benson John, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution: Or, Illustrations by Pen and Pencil of the History, Biography, Scenery, Relics and Traditions, of the War for Independence (New York : Harper & Bros., 1851) <http://archive.org/details/pictorialfieldbo02lossuoft> [accessed 25 November 2020]

- McGeachy, John, Revolutionary Reminiscences from the ‘Cape Fear Sketches’ (North Carolina State University, 2002)

- Norris, David, Wilmington Fortifications, E-mail, 10/13-14/2020

- O’Kelley, Patrick, Nothing but Blood and Slaughter: The Revolutionary War in the Carolinas, Volume Three, 1781 (Booklocker.com, Inc., 2005)

- Rankin, Hugh F., ‘The Moore’s Creek Bridge Campaign, 1776’, The North Carolina Historical Review, 30.1 (1953), 23–60

- Rankin, Hugh F., The North Carolina Continentals (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1971)

- ‘Reminiscences of an Old Fort Built by the British in Wilmington 1781’, The Daily Review (Wilmington, N.C., 11 November 1881)

- Russell, Phillips, North Carolina in the Revolutionary War (Charlotte, N.C.: Heritage Printers, Inc., 1965)

- Schaw, Janet, and Evangeline Walker Andrews, Janet Schaw, ca. 1731-ca. 1801. Journal of a Lady of Quality; Being the Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the Years 1774 to 1776. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1921) <https://www.docsouth.unc.edu/nc/schaw/schaw.html> [accessed 7 January 2021]

- Sherman, Wm. Thomas, Calendar and Record of the Revolutionary War in the South: 1780-1781, Tenth Edition (Seattle, WA: Gun Jones Publishing, 2007) <https://www.americanrevolution.org/calendar_south_10_ed_update_2017.pdf>

- ‘Travel through History: African American Placemaking on the Lower Cape Fear’, African American Heritage Museum of Wilmington <http://www.aahfwilmington.org/aahmw_virtualexhibits_placemaking_home.html> [accessed 17 February 2020]

[1] Reproduced in Butler 1976.

[2] Dunkerly 2012.

[3] The Regulators coordinated across counties in the 1760s, but their complaints were specific to the N.C. colonial government, not the British king and Parliament.

[4] Hooper, et al., 1774.

[5] ‘Resolutions by Inhabitants of the Wilmington District Concerning Resistance to Parliamentary Taxation and the Provincial Congress of North Carolina’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1774 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr09-0285> [accessed 17 December 2020].

[6] Schaw 1921.

[7] Dunkerly.

[8] Rankin 1953.

[9] Ibid.

[10] At the time of the war this was called Negro Head Point. One explanation for the name is that the head of a man executed for trying to escape slavery was displayed there, to warn others against seeking their freedom.

[11] Story transcribed in McGeachy 2002; caveats from Dunkerly.

[12] Bloodworth Street in Raleigh is named for him.

[13] Dunkerly.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Lee 1965.

[16] Dunkerly.

[17] Ingram 2020.

[18] Hunter Ingram.

[19] Lamberton 2020.

[20] Contrary to local traditions, Cornwallis did not stay in the house; Patriot prisoners were not held in the old jail; no floorboards were damaged by guards’ muskets; and a soldier did not scratch his eventual wife’s name in a windowpane (Hunter Ingram; Ingram 2020; Lamberton 2020).

[21] Ingram 2020.

[22] Norris 2020.

[23] Reproduced in Butler.

[24] Drane 1843. One doubt raised about this story is why the British would desecrate an Anglican Church. Norris reports St. James hadn’t had a minister or services for five years, so maybe the British did not consider it consecrated anymore. However, the story may also be anti-Tarleton propaganda, since many negative stories about him proved untrue.

[25] Greenfield: Dunkerly.

[26] Norris.

[27] Dunkerly.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Based on an overlay of the 1781 map on the modern street grid; speculations by two modern scholars (De Van Massey 1987, Dunkerly); a local historian who has studied the war period (Norris); typical military practices of the time; and the current landforms. Though the hill has been altered over the centuries, the primary changes made the top flat. The edges appear to retain the shape of the colonial period.

[33] Dunkerly.

[a] Russell 1965.

[b] Hall 1992.

[c] Multiple sources claim Lt. Col. “Light Horse” Henry Lee was with them. Maj. Joseph Graham confirms Lee was at Rutherford’s camp the day before, but says Lee met up with Graham’s force southwest of the Wilmington area on this date, having come directly from the camp (Graham, William A., General Joseph Graham and His Papers on North Carolina Revolutionary History [Edwards & Broughton, 1904] <http://archive.org/details/cu31924032738233>).

[i] Moore’s Creek National Battlefield, ‘Negro Head Point Road’ (United States Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service); Angley, Wilson, Preliminary Findings and Observations Concerning the History of the Negro Head Point Road (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Division of Archives and History Research Branch, 20 August 1984), Pender Co. Public Library Vertical Files.

[ii] O’Kelley 2005.

[iii] Howell 1959.

[iv] Rankin 1971.