A Fifer and a Constitution

Context

Context

Cross Creek and nearby Campbelltown form a Patriot economic center after 1776, but start as Loyalist strongholds.

Situation

The first group of Europeans to occupy this region were Scottish immigrants of the 1739 Argyll Colony, built up in subsequent waves in the 1750s and ’60s. Cross Creek was founded in 1756 along the creek by that name. By the time of the American Revolution, it “had over forty buildings, including taverns, a brewery, mills, a tannery, the county jail, stores, and warehouses, making it a crossroads for trade and communication. Many craftsmen resided here, including merchants, coopers, blacksmiths, tailors, weavers, shoemakers (known as cordwainers), hatmakers, brewers, brickmakers, bridlemakers, joiners, wagoners, wheelwrights, rope makers, and wool combers.”[1] These lived in 60–70 households.[2]

Formally incorporated in 1762, Campbelltown was the farthest point up the Cape Fear River boats could navigate from the coast. Centered where Person Street now meets the river, its port facility helped the area becomes a critical point for the exchange of imported goods and inland products, though by the war it was down to a few warehouses and an old courthouse.[3]

Though the towns merged in 1778, wartime sources still called it “Cross Creek” even though that part officially became “Upper Campbelltown.” Wagons regularly passed between here and distant Hillsborough, Salem (now Winston-Salem), and Salisbury throughout the war.

A devastating post-war fire mentioned below destroyed records and letters that might have answered many questions about Revolutionary events in Fayetteville. Stories and exact locations now often come from single sources or conflict with each other. Believe with caution!

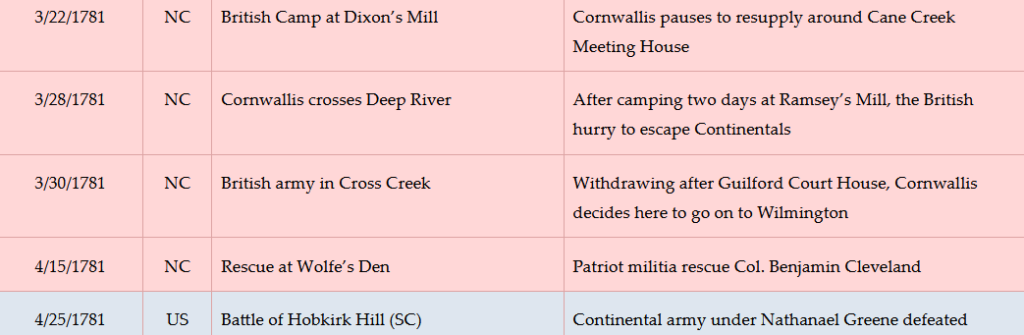

Date

Tuesday, June 20, 1775–Sunday, April 1, 1781.

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

Liberty Point

From Market Square, walk one block east on Person Street, to the triangle formed where Bow Street angles back to the left. The current park is only part of the “point” at the time. Person Street did not exist, so the point was formed by today’s Bow Street meeting an early, straighter version of Franklin Street further east (ahead of you).

From Market Square, walk one block east on Person Street, to the triangle formed where Bow Street angles back to the left. The current park is only part of the “point” at the time. Person Street did not exist, so the point was formed by today’s Bow Street meeting an early, straighter version of Franklin Street further east (ahead of you).

After the Battle of Lexington and Concord (Mass.) in April 1775, “committees of safety” made up of property owners around North Carolina began issuing resolutions of support for the northern Patriots. At a tavern here or nearby, local men sign a document written in Wilmington on Tuesday, June 20, by local political leader and later militia officer Robert Rowan. (It is unclear why he wrote it there.) However, the text was mostly lifted from a June resolution by the South Carolina Provincial Congress. Officially named the “Cumberland Association,” the document mentions the Massachusetts battles and states in part:

“We therefore the subscribers of Cumberland County, holding ourselves bound by that most sacred of all obligations, that duty of all good citizens towards an injured country, and thoroughly convinced that under our distressed circumstances, we shall be justified before God and man in resisting force by force; Do unite ourselves under every tie of religion (and) honour and associate as a band in her defence (against) every foe, hereby solemnly engaging that whenever our continental or Provincial Councils shall decree it necessary, we will go forth and be ready to sacrifice our lives and fortunes to secure her freedom and safety…”

Eventually 55 men sign it. Among them are James Emmet, later the colonel in charge of the Cumberland Militia (part-time soldiers); James Gee, owner of one of America’s early hat factories; men who fought in both the Patriot militia and regular Continental Army; and two men who joined a Highlander army in support of the British government six months later.[4]

The agreement has come to be known as the “Liberty Point Resolves.” Though it did not declare independence, it is believed to be the second-oldest mutual defense pact against the royal government in America, after the Mecklenburg Resolves from Charlotte. The monument in the triangle lists the signers.

If you wish to avoid a four-block round-trip walk to our next stop by driving, use these directions (walkers, skip to the next section):

- Drive one block past Bow on Person Street to the roundabout at Cool Spring Street, and take it to the left.

- Drive a little over a block, veering slightly left to cross Cross Creek.

- Take the first left, Meeting Street.

- Turn left and park in the lot.

- Go to the fountain and skip the next set of walking directions.

A Loyalist Army Forms

Walk around the triangle and left up Bow Street. You are now on the original main street of Cross Creek, shown on a 1770 map as connecting to the road south to Wilmington and, in the direction you are walking, the western towns mentioned earlier. Go to the first intersection, Green Street, and turn right.

Take the bridge over Cross Creek and turn right (east) into Linear Park. After crossing the creek again on the walking bridge, go around the circle and take the sidewalk from the left side. Follow it across Ann Street and then right to the Cool Spring fountain.

Six months before the Declaration of Independence, the British government has already lost control of the Province of North Carolina. Royal Gov. Josiah Martin has fled New Bern and is living on a ship off the mouth of the Cape Fear River. At Martin’s suggestion, two British armies are converging there by sea to take the colony back, and Martin has called for loyal volunteers to join them.

Six months before the Declaration of Independence, the British government has already lost control of the Province of North Carolina. Royal Gov. Josiah Martin has fled New Bern and is living on a ship off the mouth of the Cape Fear River. At Martin’s suggestion, two British armies are converging there by sea to take the colony back, and Martin has called for loyal volunteers to join them.

Nearly 1,600, most of them Scottish Highlanders, gathered in the vicinity. At least one camp likely is here and in the open fields across the creek between the two towns, taking advantage of Cross Creek, distant Blount Creek, and the Cool Spring for water. (Surviving documents do not specify the campsite. Local traditions also suggest a plantation south of town[5] or more in the modern downtown.[6])

As historians have noted, “These Loyalists were farmers, not fighters. The men were not a militia unit nor an army of experienced soldiers. They had not trained together nor fought together, and they were ill equipped and poorly supplied.”[7] Some are here because they, to gain permission to immigrate, or their grandfathers after the 1746 Battle of Culloden in Scotland, had sworn an oath of loyalty to the king. Others are responding to the offer of confiscated rebel land and twenty years of no property taxes.

A few are ex-Regulators, former protestors against the colonial government who had sworn a loyalty oath in exchange for pardons after losing the Battle of Alamance five years earlier. However, one source says 500 of these turned around and left when they found none of the British soldiers they had been promised.[a] Another says only small groups remain, and their leaders point out their weapons were confiscated as part of the pardon agreement.[b]

On Sunday, February 18, 1776, the recruits march toward Brunswick Town to join the governor, via the Wilmington Road.

Contrary to local tradition, Scottish heroine Flora Macdonald, whose husband Allan was one of the Loyalist (“Tory”) army leaders, almost certainly did not address them prior to their departure.[8] Perhaps she should have. The Tories never made it to the British. First blocked at Rockfish Creek south of town, they were badly defeated at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge. Only a few made it back to Cross Creek before getting captured by Patriot militia.

Fifer Grave

Walk to the large monument on the left, and go to the far side. Turn around and face the grave to its left.

Believed to be from the Roanoke River valley, Isaac Hammond volunteered to serve with a North Carolina regiment in the regular Continental Army during the war. He became its fifer at age 15. He was just one of hundreds of African-Americans who fought for the new United States.

Believed to be from the Roanoke River valley, Isaac Hammond volunteered to serve with a North Carolina regiment in the regular Continental Army during the war. He became its fifer at age 15. He was just one of hundreds of African-Americans who fought for the new United States.

Fifers were not recruited for entertainment, though they provided that as well. Fife-and-drum units conveyed orders, with different tunes meaning specific commands. These instruments were chosen because the fife’s high pitch and the drum’s low pitch could be heard over the sounds of battle.

Hammond later earned his living as a barber. He and his post-war wife Dicey were among the 10% of blacks in Campbelltown who were free in the 1790 census.[9] When a local militia company was formed in 1793, Hammond joined as its fifer and remained for 30 years. This area was the company’s parade grounds. Hammond was buried here at his request, with military honors, “in uniform with fife in hand.”[10]

Cornwallis Campsite

Walk back to Green Street and turn left back to Bow. If you drove, return to Bow Street, turn right, and park on it or across Green.

Either way, cross Green Street to Maiden Lane. Face Market Square a block south.

In late March 1781, about 500 Patriot (“Whig”) militia are trying to remove or burn supplies all over town, before probably pulling out to the east across the river at Campbelltown with whatever they can carry. They were ordered to collect all of the boats in the area as well.[c] Cross Creek, solidly in Patriot hands for the four years since Moore’s Creek, has become a major military supply depot for the Southern Department of the Continental Army. In 1781 the commander is Gen. Richard Caswell. This first state governor had taken the role after hitting the term limit of three consecutive terms per the first state constitution. The depot kept busy over the years “acquiring, storing and shipping salt, leather, beef, pork, wheat and (horse) forage” for both regular and militia troops from N.C.[11]

In late March 1781, about 500 Patriot (“Whig”) militia are trying to remove or burn supplies all over town, before probably pulling out to the east across the river at Campbelltown with whatever they can carry. They were ordered to collect all of the boats in the area as well.[c] Cross Creek, solidly in Patriot hands for the four years since Moore’s Creek, has become a major military supply depot for the Southern Department of the Continental Army. In 1781 the commander is Gen. Richard Caswell. This first state governor had taken the role after hitting the term limit of three consecutive terms per the first state constitution. The depot kept busy over the years “acquiring, storing and shipping salt, leather, beef, pork, wheat and (horse) forage” for both regular and militia troops from N.C.[11]

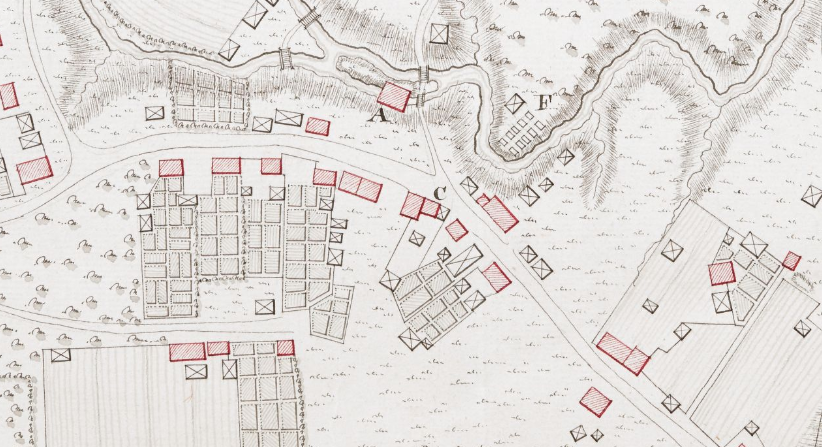

Now, however, British Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis is headed this way. His army was badly hurt in its “victory” at the Battle of Guilford Court House (in today’s Greensboro) over the Continental army of Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene. It is coming here because Cornwallis thinks Cross Creek is under Loyalist control. On Friday, March 30, around 1,700 Redcoat infantry and cavalry, plus artillery, wagons, camp followers, and people escaping slavery, march down Maiden Lane from the right. They had crossed the creek a few hundred yards upstream.

The British probably set up along the banks of Cross and Blount creeks.[12] Their camp would have covered all of the modern downtown area, overlapping the likely 1776 Tory campsite.

Turn around and go to the Linear Park sidewalk along the creek on this side of Green. Follow it left to the first overlook on the right.

Maps of the time suggest the far bank was an island and another channel of the creek ran on the other side, filled in since then. Cochran’s Mill crossed the creek onto this side from the island; you might be standing inside it!

Maps of the time suggest the far bank was an island and another channel of the creek ran on the other side, filled in since then. Cochran’s Mill crossed the creek onto this side from the island; you might be standing inside it!

Some evidence says Cornwallis stayed in the home of John Dobbin, facing the creek on that farther bank. The house was moved after the war, but existed until 1939. As described by people who saw it in later years, it was “a story and a half, with three dormer windows across the front, and also the back. The piazza (porch) extended across the front and was enclosed with balusters very thin and graceful. There was a large paneled entrance doorway” and “floor-length windows.”[13] A visible brick foundation at this location enclosed a full basement.

The British begin foraging for food and clothing, but have little success. An 1854 pastor who collected stories from people alive during the war claims the town baker, Lewis Bowell, makes a clever escape.[14] Bowell hides inside one of his empty barrels upstairs. Apparently his supplies had been evacuated. While the British are searching, they happen to pick up the barrel and send it down the stairs with a kick. On hitting a wall at the bottom, the barrel breaks open and Bowell emerges.[15] At that point the stunned British just leave, empty handed.

That story illustrates the army’s desperate straits. Cornwallis writes that they had “‘but little provision & no forage; the army was barefooted & there is the utmost want of necessaries of every kind; and I was embarrassed with about 400 sick & wounded. These considerations made me determined to march down to Wilmington.’”[16] He had assumed supplies could be sent from Wilmington by river. Only upon arriving did he realize “‘navigation of the Cape Fear River to Wilmington (is) impracticable, for the distance by water is upward of (a) hundred miles, the breadth seldom above one hundred yards, the banks high, and the inhabitants on each side generally hostile.”[17] In other words, any supply boats would be slow-moving ducks for Patriot snipers.

Also frustrated were his hopes for aid from Tories, a problem plaguing his entire N.C. campaign. As he wrote to the overall British commander in North America, Sir Henry Clinton: “‘The Inhabitants rode into Camp, shook me by the hand, said they were glad to see us and to hear that we had beat Greene, and then rode home again. For I could not get 100 Men… to stay with us.’”[18] Local Tories do bring some supplies, though, and some take advantage to destroy Whig property.[19]

Some of the British wounded die and are buried somewhere in town. On Sunday the army marches down the same route taken by the Highlander army. But Cornwallis has not left without paying for Cross Creek’s “hospitality.” Col. James Emmett, the Liberty Point signer, whose regiment has been shadowing Cornwallis, reports to Greene on an outbreak of smallpox caught from the British. And a camp follower leaves behind a baby girl in a widow’s home. As an adult she was noted on the 1850 census as “left by Cornwallis.”[20]

Loyalists Raid and Leaders Assemble

Go back to Green Street and walk across Maiden Lane.

In 1779, the Cumberland Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions meets for the first time in the new, unfinished courthouse here, possibly where you stand. In August 1781, a Tory army of 300–400 men, many of them Highlanders, capture Patriots here and around town in a raid. Emmett wrote Gov. Thomas Burke that month, “I am under the disagreeable necessity of informing your Excellency that, on Thursday last, the 14th… between nine and ten o’clock in the morning, this town was, in the most sudden manner imaginable, surprised by a party of the enemy… They entered the town in so sudden and secret a manner that it was out of the power of any man who was in it to make his escape.”[d] Emmett said he was a mile away and escaped over the river, but was caught after coming back to avoid capture by another force. He was freed, and some of the prisoners were rescued in the Battle of Elizabethtown 11 days later.

In 1779, the Cumberland Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions meets for the first time in the new, unfinished courthouse here, possibly where you stand. In August 1781, a Tory army of 300–400 men, many of them Highlanders, capture Patriots here and around town in a raid. Emmett wrote Gov. Thomas Burke that month, “I am under the disagreeable necessity of informing your Excellency that, on Thursday last, the 14th… between nine and ten o’clock in the morning, this town was, in the most sudden manner imaginable, surprised by a party of the enemy… They entered the town in so sudden and secret a manner that it was out of the power of any man who was in it to make his escape.”[d] Emmett said he was a mile away and escaped over the river, but was caught after coming back to avoid capture by another force. He was freed, and some of the prisoners were rescued in the Battle of Elizabethtown 11 days later.

Continue one block to Market Square.

Here where the 1831 Old Town Hall stands today, town leaders built in 1778 a brick building they hoped would sway the General Assembly to name Cross Creek the permanent capital city.

Here where the 1831 Old Town Hall stands today, town leaders built in 1778 a brick building they hoped would sway the General Assembly to name Cross Creek the permanent capital city.

Though a state convention after the war chose to build a new capital and capitol instead, the state assembly met here several times before Raleigh was ready to host it. A number of Revolutionary leaders had key roles in the assembly’s vote here to create the University of North Carolina in 1789, which became the first U.S. public university to open its doors. Many of the same men attended the state’s Second Constitutional Convention held in the building that year, which ratified the U.S. Constitution. Richard Caswell died during the convention, and his funeral was here (detailed at his grave on the Kingston page).

The State House was one of 600 buildings burned down by a catastrophic 1831 fire. The blaze started in the chimney of a house on the corner you are standing on.

Before going to the next section, look at the “Historical Tidbit” below.

Council Hall

Go back to your vehicle and:

- Take Person Street to Cool Spring Street.

- Turn right at the roundabout.

- Drive four blocks (the second one is long), and turn right on Butler Street.

- Park partway up the block, before reaching the first right turn, Hall Street.

Probably on or near the intersection ahead of you stood Council Hall. (The streets were not here then.) This home built around 1735 was named for its original owner, James Council, and bought by Peter Mallett in May 1777, a merchant and owner of several mills.[21] One, a cotton mill, was downhill to your left on Blount Creek.[22] Mallett served as a commissary (supply) officer in the regular Continental Army and probably later led a militia company. He was also on the committee of safety that became the local government, and a member of the state House of Commons. In addition to this house, he had a plantation downriver during the war.

Probably on or near the intersection ahead of you stood Council Hall. (The streets were not here then.) This home built around 1735 was named for its original owner, James Council, and bought by Peter Mallett in May 1777, a merchant and owner of several mills.[21] One, a cotton mill, was downhill to your left on Blount Creek.[22] Mallett served as a commissary (supply) officer in the regular Continental Army and probably later led a militia company. He was also on the committee of safety that became the local government, and a member of the state House of Commons. In addition to this house, he had a plantation downriver during the war.

In a letter or journal—the original form is unclear—Mallett recounts a scary and dramatic night just before Cornwallis’s arrival. About 40 Loyalists under “a Mr. Swain” approach the house and demand supplies for the British, though Mallett calls this a pretense to steal them. He refuses to let them in, but is outnumbered. His militia unit is away, and only one other man is at the house, an enslaved African-American, “Johnny.” Fortunately, he also has two women.

“‘After an hour or two parley, they forced (their way) into the lower part of the house, and my wife, myself, Johnny, and a (black) woman defended ourselves with arms; not only forced them from the stairway, but out of the house. One gun only was fired. My wife and servant Hannah were noble soldiers.’”[23] He had married his wife, Sarah, just five months before. They went on to raise 14 children here and in a larger house to the west of town, including one child from his previous marriage.

The British army arrives a few days later, with some old friends. Mallett says he knew some of the officers from the “‘Canada War,’” part of the French & Indian War of the 1750s. He has gone into hiding somewhere across the Cape Fear. One of his aunts by marriage and another woman come to him to say Cornwallis visited the house with some officers, presumably the ones Mallett knows. They took his goods in Cross Creek, including items at the house. Mallett’s account is unclear on this point, but appears to say he was told he could keep the goods he had in Wilmington if he joined Cornwallis as a commissary officer. “‘This I absolutely refused, having been for years in the American army, I could not think of acting against them…’”[24]

Moved and renovated by Mallett’s son in the 1830s, the house later was moved again to the campus of Methodist University on Ramsey Street. (Greene Street becomes Ramsey north of downtown.) Now called the Mallett-Rogers House, it holds university offices.

Historical Tidbit

In 1783, greater Campbelltown became the first city in the United States to rename itself for one of the most famous figures of the war, the Marquis de Lafayette. This French volunteer officer in the Continental Army became a protégé and close friend of Gen. George Washington. In 1825, Lafayette made a tour through the southern U.S., and stopped here on March 4 and 5. Lafayette stayed at the home of Duncan McRae, located where the courthouse is now, one block south of Market Square.

More Information

- ‘American Independence Trail’, Fayetteville Area Convention and Visitors Bureau <https://www.visitfayettevillenc.com/things-to-do/cultural-heritage-trails/american-independence-trail/> [accessed 28 March 2020]

- Bleazey, Heidi, and Bruce Daws, Fayetteville Area Transportation Museum, In-person interviews, 10/1/2020

- Caudill, William, Director, Scottish Heritage Center, Interview with tour, 10/1/2020

- Caruthers, E. W. (Eli Washington), Revolutionary Incidents and Sketches of Character, Chiefly in the ‘Old North State’ (Philadelphia, Hayes & Zell, 1854) <http://archive.org/details/revolutionaryinc00caru> [accessed 17 April 2020]

- Clark, David, ‘Additional Information Concerning the Liberty Point Resolves (Cumberland Association) [Memorandum for: Committee for Development of Historical Material, Cumberland County Bicentennial Commission]’, 24 October 1975, Cumberland County Public Library, Local & State History Department

- Crane, David, ‘The Signing of the Liberty Point Resolves’, The Fayetteville Observer and the Fayetteville Times (Fayetteville, N.C., 22 June 1975)

- Cumberland Association (handout), Fayetteville Area Transportation Museum [viewed 1 October 2020]

- ‘Cumberland Association Papers, 1775; 1830.’, UNC University Libraries <https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/02075/> [accessed 21 April 2020]

- Dunkerly, Robert M., Redcoats on the Cape Fear: The Revolutionary War in Southeastern North Carolina, Revised (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2012)

- ‘Exhibits’ (Museum of the Cape Fear, Fayetteville, N.C., 2020)

- Haynes, Kenneth, ‘Lord Charles Cornwallis’s March Down the Cape Fear River’, NCGenWeb, 2006 <http://ncgenweb.us/cumberland/1776revolution.html> [accessed 24 January 2020]

- ‘Isaac Hammond Memorial, Fayetteville’, Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina, 2010 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/395/> [accessed 21 April 2020]

- Johnson, Lucile Miller, Hometown Heritage, First Edition (Fayetteville, N.C.: The Graphic Press, Inc., 1978)

- Jones, Randell, Before They Were Heroes at King’s Mountain, North Carolina/Tennessee Edition (Winston-Salem, NC: Daniel Boone Footsteps, 2011)

- Leclercq, Matt, ‘FayWHAT? What’s so Special about Hay Street’s Live Oak?’, The Fayetteville Observer <https://www.fayobserver.com/news/20181021/faywhat-whats-so-special-about-hay-streets-live-oak> [accessed 20 April 2020]

- ‘Liberty Point Resolves Declaration of Independence, Fayetteville’, Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina, 2010 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/31> [accessed 20 April 2020]

- MacRae, John, ‘This Plate of the Town of Fayetteville North Carolina, so Called in Honor of That Distinguished Patriot and Philanthropist Gen’l La Fayette Is Respectfully Dedicated to Him by the Publisher’, North Carolina Maps, 1825 <https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ncmaps/id/127> [accessed 15 December 2020]

- Mallett, Peter, ‘Peter Mallett’s Journal, 1744-1805’, Cumberland County Public Library files

- ‘Marker: I-14’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=I-14> [accessed 17 December 2020]

- Moulder, Sana, Local & State History, Cumberland County Public Library, ‘Revolutionary-Era Questions’, E-mail, 30 December 2020

- Oates, John A., The Story of Fayetteville and the Upper Cape Fear (Fayetteville, N.C.: Woman’s Club of Fayetteville, 1950) <https://archive.org/details/storyoffayettevi00john>

- Pancake, John S., This Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas, 1780-1782 (University, AL : University of Alabama Press, 1985) <http://archive.org/details/thisdestructivew00panc> [accessed 13 October 2020]

- ‘Parade Grounds’, Fayetteville Independent Light Infantry Official Website <https://www.fili1793.com> [accessed 21 April 2020]

- Parker, Roy, ‘Fayetteville’, NCpedia, 2006 <https://www.ncpedia.org/fayetteville> [accessed 28 March 2020]

- Parker, Roy, The Best of Roy Parker, Jr. (Pediment Publishing, 2007)

- Rankin, Hugh F., The North Carolina Continentals (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1971

- Sherman, Wm. Thomas, Calendar and Record of the Revolutionary War in the South: 1780-1781, Tenth Edition (Seattle, WA: Gun Jones Publishing, 2007) <https://www.americanrevolution.org/calendar_south_10_ed_update_2017.pdf>

- Wilkins, Tim, ‘After 230 Years, Document Still Shows “Resolve”’, Up and Coming Weekly <https://www.upandcomingweekly.com/2-uncategorised/349-after-230-years-document-still-shows-resolve> [accessed 20 April 2020]

[1] Dunkerly 2012.

[2] Parker 2007.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Cumberland Association (handout); the original association document is in Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[5] Where NC 87 now intersects Mountain Drive.

[6] Parker 2007.

[7] Jones 2011.

[8] The story from a single source is highly unlikely, for reasons including the distance (140 miles round trip), the fact her husband left separately, and her possibly having three grandchildren in her care. See our Flora Macdonald page for the full explanation and sources.

[9] Parker 2007.

[10] Parade Grounds.

[11] Parker 2007.

[12] An 1854 source (Caruthers) says the British camped at Haymount Plantation, later the site of an arsenal and now of the Museum of the Cape Fear. He does not cite his source. The location may be a misreading of a report that they camped on a ridge one mile west of town. If the “town” was Cross Creek, he could be right; if the town was Campbelltown, the description fits the current downtown area. Exhibits at the museum (2020) make no mention of a camp. Also, Cornwallis did not typically make his headquarters far outside his camp, as would have been the case given what you will read next in the text.

[13] Johnson 1978.

[14] Caruthers 1854.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Haynes 2006.

[17] Dunkerly.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Parker 2007.

[21] Fields, William, ed., Abstracts of Deeds of Cumberland County, North Carolina: Volume Two, Books 4-7, 1770-1785 (Fayetteville, N.C.: Cumberland Co. Public Library & Information Center).

[22] MacRae 1825; the mill and home were owned by Mallet’s son when this map was drawn in 1825. One source (Parker 2006) seems to say the home was across the hill, where an N.C. Department of Transportation district headquarters is today. More likely that area was just part of the Mallet property, and the location chosen for the family cemetery. Nicer homes were usually built on heights like the one here, with cemeteries placed some distance away from them.

[23] Mallett.

[24] Johnson.

[a] Pancake 1985.

[b] Rankin 1971.

[c] Per Nathanael Greene’s orders, quoted in Sherman 2007.

[d] Quoted in Caruthers.

← McNeill Grave | Tory War Tour | Black Swamp →