A Female Spy Aids a Surprise

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 34.6280, -78.6079.

Type: Sight

Tour: Tory War

County: Bladen

![]() Full

Full

Park anywhere near the coordinates, at the intersection of King Street and Martin Luther King Drive in downtown Elizabethtown.

All stops are visible from a sidewalk or parking lots.

Context

With a British Army corps camped in Wilmington in 1781, Loyalists have come to dominate the region between there and Cross Creek (Fayetteville) in their ongoing civil war with the Patriots.

With a British Army corps camped in Wilmington in 1781, Loyalists have come to dominate the region between there and Cross Creek (Fayetteville) in their ongoing civil war with the Patriots.

Situation

Tory

A Loyalist (“Tory”) force of 300–400 men under Col. John Slingsby, many of them Scottish Highlanders, has been raiding Patriot (“Whig”) homes throughout the area. At Slingsby’s base camp in Elizabethtown, the Tories are holding Whigs captured at the Cumberland County Courthouse in Cross Creek. Meanwhile, another Tory unit under the infamous Col. David Fanning is returning to the area from Wilmington.

Patriot

A group of 60–70 Patriots, including refugees from the Elizabethtown area, are hiding in the next county north (Duplin at the time). Sources differ on who was in command of the Whigs, or why. Most say Col. Thomas Robeson, because regular commander Col. Thomas Brown had either skirmish wounds or smallpox. Regardless, they decide to march on the Loyalists despite being outnumbered. Sources again differ on the reasons, suggesting it was to free the prisoners; to block Fanning; or simply out of desperation to stop the Tory raids. The men march two days with no tents or food, but find a secret weapon near their new camp.

Date

Monday, August 27, 1781.

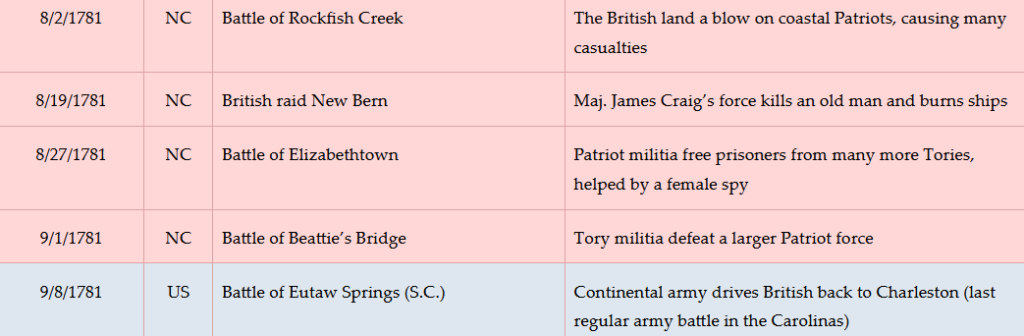

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

A Spy, a Surprise, and Lies

Walk to the intersection of King Street and Martin Luther King (MLK) Drive.

Elizabethtown, founded to support the new Bladen County Courthouse, is only five years old in 1781 and growing slowly. (The old courthouse three miles upriver burned in 1768.) Plantations supplying materials used in shipping, like tar and wood, are springing up along the river around town. However, building supplies are harder to get during the war, so there are only around 20 property owners here.[1] The town runs a couple blocks on either side of Poplar Street (a block southeast), along both sides of what still is the main road today, Broad Street.

Elizabethtown, founded to support the new Bladen County Courthouse, is only five years old in 1781 and growing slowly. (The old courthouse three miles upriver burned in 1768.) Plantations supplying materials used in shipping, like tar and wood, are springing up along the river around town. However, building supplies are harder to get during the war, so there are only around 20 property owners here.[1] The town runs a couple blocks on either side of Poplar Street (a block southeast), along both sides of what still is the main road today, Broad Street.

In a February 1781 letter written here to Brig. Gen. Alexander Lillington, Brown expressed the frustrations of local Patriots since the British had taken Wilmington the month before (spellings original): “‘I will gard the river… as far as lies in my power, but the greatest part of the good people in this County is Engaged back against the Toryes, and seems Very Loth to go Against the British And Leive their Families Exposed to a set of Villians, who Dayley threattains their Destruction.'”[a]

Little has changed six months later. Tories are camped all around this spot on Sunday evening, August 26. They have posted sentries on all four sides of the camp.[2]

Sallie Salter, 39-year-old unmarried daughter of an influential family, wanders the camp selling eggs. She had approached a ferry running where Poplar Street now crosses the river (visited later). The Tories had gathered all the boats in the area on this side, but she talked a sentry into bringing her over. When done, she goes back across.

The Patriots were camped by her family home. One secondhand source says she overheard their decision that someone should scout the camp and volunteered. She reports back with the information they need to plan a surprise attack. Nothing else is known about Salter, except that her father was supposedly a soldier away from home at the time, and she died in 1800 at age 58.[3]

Despite deep hunger, the Patriots move that night, taking advantage of a bright moon.[4] They approach the far bank southeast of town. Because they can’t find any boats, they march about a mile farther downriver (to the right when facing downtown). There they strip naked, and tie their clothes and ammunition to their heads. They wade across the wide river holding their guns vertically by the barrels, so the firing mechanisms are out of the water. Though only “breast deep”[5] for some, it is nearly to the noses of others! After scrambling up the steep bank through thick canes, they get dressed and cross what now is NC 87, then the dirt King’s Highway. There they split into three groups and spread out. Two hours later, one source says, they were in position.[6]

Look east, away from downtown, out MLK Drive.

Before daybreak, the moon has gone down, and the Tories are asleep in darkness. Suddenly you hear a shot from the woods in the direction you are facing. Another secondhand account says a Tory sentry fired a warning shot into the air when an unknown party did not answer his challenge: “Stand, who goes there?” A gunshot happened to be the signal prearranged among the Patriots to start the attack, the account says, so shots and shouts now fill the night. Sentries on all sides are pushed back.[7] You see muzzle flashes throughout the woods on three sides.

Confused Tories, many half-dressed for sleeping through a summer’s night, scramble to their feet and try to return fire. From the trees they hear commands being yelled to various Patriot colonels—including some not there! The attackers are trying to sound like many different regiments. You also hear the word “Washington” shouted. Some Loyalists become convinced their attackers include the Continental cavalry of Col. William Washington, known to be in South Carolina, or even his distant cousin George Washington!

Turn around and face downtown.

Under pressure of the surprise attack, the Tories begin to fall back into town, hiding behind buildings and in houses.[8]

Another threat is at hand. Fanning had warned Slingsby that he was holding too many Whig prisoners.[9] Perhaps a sense of guilt accounts for Slingsby’s reputation as being lenient with Patriots, including those he is holding now: The Cross Creek merchant may have been violating two oaths. As a former Quaker, he must have sworn off violence at some point, since Quakers were pacifists. Also, he was captured after the Tory debacle at the 1776 Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge and imprisoned in Halifax.[10] He is probably violating the parole terms for his release by fighting for King George again. Regardless, he pays for not keeping the prisoners tied up, as they begin to grab weapons and attack Tory officers in the rear of the camp.

About this time Col. Slingsby comes out of the house he is staying in, and both he and a captain are mortally wounded. The Tories panic. Some begin running toward the river. Others retreat northwest (to the left), firing as they go. After running out of ammunition, they flee. A few simply raise their hands in surrender.

The Tory Hole

Follow the retreating Tories by walking or driving toward downtown on MLK Drive. Where it ends at Broad Street, go straight across into the parking lot. Continue to the back of the lot, until you run out of earth at the edge of a deep ravine.

Follow the retreating Tories by walking or driving toward downtown on MLK Drive. Where it ends at Broad Street, go straight across into the parking lot. Continue to the back of the lot, until you run out of earth at the edge of a deep ravine.

Many of the Loyalists fall headlong down this slope. The Patriots chasing them stop here at the edge and begin a turkey shoot of the trapped Tories, now fighting underbrush to get through to the river.

One Whig says years later, “‘I was so overjoyed that I did not feel the cravings of hunger any more than if I had just risen from the best meal I ever ate…’”[11]

This slope and the flat below became known as the “Tory Hole.”

Continentals Raid the Courthouse

Go back to Broad Street and turn left. Walk one block to the intersection with Poplar. The new courthouse was in the middle of the intersection.

Move forward a year to September 1782, five months after peace negotiations began between Britain and the United States in Paris. Continental Army Capt. Robert Raiford and 30 soldiers burst into the courthouse, where a Tory is on trial. An historian says the men believe Tories are allowed to win too many property lawsuits.[12] Raiford attacks lawyer Archibald MacLaine “‘at the bar with a naked sword, beat and dangerously wounded him… under the pretence that the said Maclain [sic] had given him sometime before abusive language, and was then defending a Tory.'”[13] He also beats the court clerk for unknown reasons, though both victims apparently survive.

Move forward a year to September 1782, five months after peace negotiations began between Britain and the United States in Paris. Continental Army Capt. Robert Raiford and 30 soldiers burst into the courthouse, where a Tory is on trial. An historian says the men believe Tories are allowed to win too many property lawsuits.[12] Raiford attacks lawyer Archibald MacLaine “‘at the bar with a naked sword, beat and dangerously wounded him… under the pretence that the said Maclain [sic] had given him sometime before abusive language, and was then defending a Tory.'”[13] He also beats the court clerk for unknown reasons, though both victims apparently survive.

Raiford then leads his men in raiding Loyalist homes throughout the area. Indicted here after he was back with the army, he was tried upon returning a year later but acquitted.

The River

To see the ferry crossing and Tory Hole, you can walk, but it is safer to drive. From the Broad/Poplar intersection:

- Drive downhill.

Note: Turn left if coming from the Broad/MLK intersection. - Just past the median and before the bridge, turn left.

- Drive to the river at the Cape Fear Access Area.

In 1781, a ferry ran where the bridge is today. Sallie Salter came to the far bank expecting to use it.

In 1781, a ferry ran where the bridge is today. Sallie Salter came to the far bank expecting to use it.

This spot played a role in a dramatic chase in 1776, five months before independence was declared. Around 1,600 Loyalists were trying to make their way from Cross Creek to Fort Johnston at the mouth of the Cape Fear River (today’s Southport), to support British troops headed there. They were blocked by 1,000 Patriots under Col. James Moore and forced to cross the Cape Fear back at Cross Creek. Moore brought his men here hoping to cut the Tories off. You could have watched for hours as the men, and five cannons, crossed from this side on Friday, February 23. On learning the Loyalists had gotten past another Patriot force, though, Moore brought his men back here and loaded them on boats to take downriver. The delay caused them to miss by a few hours the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge.[b]

Go back partway up the hill, and turn right into Tory Hole Park.

Go back partway up the hill, and turn right into Tory Hole Park.

The slope you visited from above is on the far side of the parking lot. At the end of the battle you would have seen dozens or hundreds of men dragging themselves free of the bushes on the slope, and then rushing into the trees and canes along the river to escape.

Battle Map

The Battle of Elizabethtown: All locations are approximate. 1) Spy crosses river, explores camp. 2) (Next day) Patriots cross downstream. 3) Patriots launch surprise attack. 4) Tories flee west, north. 5) Patriots continue fire at ravine edge.

Casualties

- Tory: 16–19 killed, wounded or captured.

- Patriot: 2–4 wounded.

After the Battle

Though their losses were small, many of the Tories went home for good. This rout by a much smaller force finally broke the Loyalist hold on this region. But hostilities continued in the state for another year, as demonstrated above and on our Tory War Tour.

Historical Tidbit

On the way from the Battle of Guilford Court House (in today’s Greensboro) to Wilmington, the main British army under Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis camped somewhere south of Elizabethtown on Brown’s Creek, on Tuesday, April 3, 1781. There it had the sad duty of burying one of its wounded from the battle, Lt. Col. James Webster, who had died at their previous campsite at Black Swamp.

More Information

- Barefoot, Daniel, Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1998)

- ‘Battle of Elizabethtown Culminated at the Tory Hole’, NC DNCR <https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2016/08/27/battle-of-elizabethtown-culminated-at-the-tory-hole> [accessed 18 January 2020]

- Beasley, R.F., ‘The Battle of Elizabethtown’ (presented at the Annual Celebration at Guilford Battle Ground, Greensboro, N.C., 1901)

- Brown, A.A., ‘Battle of Elizabethtown (2/21/1844 Letter), Reprinted from Wheeler, John, Historical Sketches of North Carolina’, in Elizabethtown Bicentennial, 1773-1973 (Elizabethtown, N.C.: The Elizabethtown Town Board, 1973)

- Dunkerly, Robert M., Redcoats on the Cape Fear: The Revolutionary War in Southeastern North Carolina, Revised (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2012)

- Elizabethtown Bicentennial, 1773-1973 (Elizabethtown, N.C.: The Elizabethtown Town Board, 1973)

- Hatch, Charles, The Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge (Office of History and Historic Architecture, U.S. National Park Service, 1969)

- Josiah Singletary (Veteran’s Pension Application), Bladen Co. Court of Please and Quarter Sessions, W. 60641833, 1833

- Kemp, Joseph, ‘Memoirs of Joseph Richard Kemp’, n.d. [Vertical files, Bladen County Public Library, accessed 11 November 2020]

- Lewis, J.D., ‘Tory Hole’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2014 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_tory_hole.html> [accessed 18 January 2020]

- Map, n.d. [Vertical files, Bladen County Public Library, accessed 11 November 2020]

- ‘Marker: I-11’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=I-11> [accessed 4 September 2020]

- Odom, Nash, ‘A Little Known Hero, Battle of Elizabethtown’, The Bladen Journal (Elizabethtown, N.C., 22 November 1971)

- Odom, Nash, ‘Sallie Salter: Fact or Legend’, The Bladen Journal (Elizabethtown, N.C., 22 April 1972)

- Rankin, Hugh F., The North Carolina Continentals (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1971)

- Ross, Malcolm, The Cape Fear (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1965)

- Russell, Phillips, North Carolina in the Revolutionary War (Charlotte, N.C.: Heritage Printers, Inc., 1965)

- Sherman, Wm. Thomas, Calendar and Record of the Revolutionary War in the South: 1780-1781, Tenth Edition (Seattle, WA: Gun Jones Publishing, 2007) <https://www.americanrevolution.org/calendar_south_10_ed_update_2017.pdf>

- Tetterton, Beverly, ‘Elizabethtown, Battle Of’, NCpedia, 2006 <https://www.ncpedia.org/elizabethtown-battle> [accessed 18 January 2020]

- ‘The Battle of Elizabethtown’ (From the Rev. Heller’s ‘History of Bladen’), n.d. [Vertical files, Bladen County Public Library, accessed 11 November 2020]

- Troy, Robert, ‘Cain’s Account (3/12/1845 Letter), from The Fayetteville Observer’, in Elizabethtown Bicentennial, 1773-1973 (Elizabethtown, N.C.: The Elizabethtown Town Board, 1973)

[1] Elizabethtown Bicentennial 1973.

[2] Brown 1844, relayed from two eyewitnesses.

[3] Odom 1972.

[4] Dunkerly 2012.

[5] Troy 1845.

[6] Brown.

[7] Troy.

[8] Brown.

[9] Dunkerly.

[10] Ibid.

[11] James Cain, quoted in Troy.

[12] Russell 1965.

[13] Quoted in Rankin 1971 from contemporary records.

[a] Quoted in Sherman 2007.

[b] Hatch 1969.

← Black Swamp | Tory War Tour | Raft Swamp →