Patriot Leader at Moore’s Creek

Location

Type: Hidden History

County: Pender

![]() None

None

The bumpy, dirt, Lillington Lane can only get you close to Alexander Lillington’s grave, which is out of sight on private property, past a gate where the lane turns right (at the coordinates 34.50, -77.80). Their home was nearby, but the exact location is unknown. If you visit, please respect the property owners’ rights by not trespassing beyond the gate, even if open.

Description

Call Him Alexander

John Alexander Lillington—who preferred his middle name—was born to a planter and politician in the Brunswick Town area. Orphaned, he was raised by his uncle, but Lillington, too, became a planter and politician. He was also a justice of the peace, and a surveyor.

Lillington’s first combat was against the Spanish during their raid on Brunswick Town in 1748. He was the assistant quartermaster (supply officer) for Royal Gov. William Tryon in defeating the Regulators at the 1771 Battle of Alamance.[1] But four years later he joined the rebellious Committee of Safety, and was elected to the Third Provincial Congress in Hillsborough.[a]

He gained fame leading units in the Patriot militia to victory at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge. Later that year, Lillington was named a colonel in charge of one of North Carolina’s Continental Army regiments, and he marched to South Carolina with it in 1777. The regiment saw no major combat, and Alexander resigned his post before it was moved north to join Gen. George Washington’s army.[2] Back home, he was elected to the state House of Commons.[3]

By 1779 he was brigadier general in command of the multi-county Wilmington District. He was sent to aid in the defense of Charleston, with 1,248 men camped just outside town.[4] They spent much of their time building fortifications. Fortunately for him, the terms of enlistment for his men ended before it fell to the British in May 1780. So he escaped becoming a prisoner of war, as happened to most NC troops there.[5]

Lillington remained in charge of the district till the end of the war. In that capacity he organized ongoing harassment of the British forces who occupied Wilmington for most of 1781, including two battles at Heron’s Bridge north of town.

His home, Lillington Hall, was not destroyed during British raids through the region. But he lost most of his possessions, and the Redcoats freed people he held in slavery. After the British left Wilmington, he reoccupied it, and returned to his life as a plantation owner. In 1783, with the war over, the commander of the Southern Continental army, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, returned to his Rhode Island home from Georgia by carriage. He visited here on Sunday, August 24.[6]

Lillington and his wife Sarah raised four children, one of whom served in the regular Continental Army.[7] He was buried in the family graveyard near his home after dying around age 60. The town of Lillington, the Harnett County Seat, is named for him, and he makes brief appearances as a character in the Outlander book and TV series.

Home and Final Resting Place

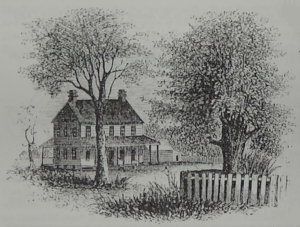

The site of Lillington Hall is unknown, but clues suggest it was within view of the modern gate where Lillington Lane takes a hard right, possibly just past the fence on the left (on private property). A magnolia tree old enough to have lived in Lillington’s time is visible to the right of the gate. Its trunk and lower branches seem to align to the tree on the right in the 1849 drawing above, which would place the house in that spot. There was a second nearby, as if they were planted as a decorative pair. Local residents have found bits of old pottery and glass in the driveway.[8] And the original driveway must have been on or near the modern lane’s route, given that the area is surrounded by a creek on the north side and swamps to the south and east.

The family cemetery is off the driveway to the right about 400 yards beyond the gate, partly surrounded by what remains of a brick wall. A marker embedded in the front says “Lillington Cemetery.” Instead of a gate, there are brick steps on the back side that allowed visitors to step over the wall.

Lillington lies in a brick tomb engraved with:

Beneath this stone

lie the mortal remains of

General

John Alexander Lillington

a soldier of the Revolution who died in 1786. He commanded the

American forces at the battle of Moore’s Creek on the 27th

February 1776 and by his military

skill and cool courage in the field

at the head of his troops, secured

a complete and decisive victory.

To intellectual powers of a high order

he united an incorruptible integrity

and a devoted and self sacrificing

patriotism. A genuine Lover of Liberty

he perilled (sic) his all to secure the

Independence of his country,

and died in a good old age,

bequeathing to his posterity the

remembrance of his virtues.

The marker may exaggerate his role at Moore’s Creek. Though he was in charge of the first Whigs to arrive, he probably gave overall command to Col. Richard Caswell after Caswell arrived with a larger force. Regardless, the earthworks he had built were key to the overwhelming Patriot victory. His son John, who lies to the left of him, served under his father there, and apparently again the last three years of the war, rising to colonel in the state militia.[9]

More Information

- ‘Articles from the Cape Fear Mercury, Volume 10, Pages 152-157’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1775 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0084> [accessed 8 September 2021]

- Chapoton, Dan, Interview and Tour, Lillington Cemetery, 6/6/2023

- ‘Gen. John Alexander Lillington (1725-1786)’, Find a Grave Memorial <https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/21174173/john-alexander-lillington> [accessed 27 May 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘John Alexander Lillington’, The Patriot Leaders in North Carolina, 2013 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/patriot_leaders_nc_john_alexander_lillington.html> [accessed 9 April 2020]

- Lillington, Alexander, ‘Letter from John Alexander Lillington to Richard Caswell, Volume 15, Pages 336-337’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1780 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr15-0239> [accessed 8 September 2021]

- ‘Lillington, John’, Encyclopedia.Com <https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/lillington-john> [accessed 8 June 2023]

- Lossing, Benson John, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution: Or, Illustrations by Pen and Pencil of the History, Biography, Scenery, Relics and Traditions, of the War for Independence (New York : Harper & Bros., 1851) <http://archive.org/details/pictorialfieldbo02lossuoft> [accessed 25 November 2020]

- ‘Marker: D-10’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=D-10> [accessed 9 April 2020]

- ‘Minutes of the North Carolina House of Commons North Carolina. General Assembly, Volume 12, Pages 265-452’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1777 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr12-0003> [accessed 8 September 2021]

- Rankin, Hugh F., The North Carolina Continentals (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1971)

- Sherman, Wm. Thomas, Calendar and Record of the Revolutionary War in the South: 1780-1781, Tenth Edition (Seattle, WA: Gun Jones Publishing, 2007) <https://www.americanrevolution.org/calendar_south_10_ed_update_2017.pdf>

- Tryon, William, ‘Order Book for William Tryon’s Regiment in the Military Campaign Against the Regulators, Volume 08, Pages 659-676’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1771 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr08-0260> [accessed 8 September 2021]

- Watson, Alan, ‘Lillington, John Alexander’, NCpedia, 1991 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/lillington-john-alexander> [accessed 9 April 2020]