Tory Leader who Kidnapped the Governor

Biography

David Fanning was not yet born when in 1755 his father, a landowning farmer in Virginia, drowned in the Deep River while looking for land in Orange County.[1] His mother moved them to what now is Wake County, but died when he was 8. Fanning eventually became a ward of a county justice in today’s Smithfield. He was treated mostly as a worker and otherwise neglected, but learned outdoor skills, horsemanship, and to read. He developed a scalp disease, likely eczema, that may have caused some baldness and led him to wear a wig in later years.[2] He first served in the militia at 16, and left home a year later. Fanning was taken in by a kinder family in Orange County for a period, and the wife cured his scalp issue. Fanning did carpentry for them and gained a reputation as a horse tamer. Eventually he moved to Upstate South Carolina, learned to trade goods with Native Americans[3], and became a farmer. He joined local Loyalist (“Tory”) militia in May 1775 that suppressed early rebels (“Whigs”). For three years Fanning fought alongside the Cherokees during their attacks on the frontier, led Loyalist units, or was in jail: He claimed he was captured 14 times, either escaping or being released each time.[4] He also rode briefly with an infamous N.C. robber, “Plundering Sam” Brown.[5] In August 1779 he took a parole from the South Carolina governor on condition of serving with the Patriots, which he did until the British captured Charleston the next May. He then returned to the King’s cause. The next month he joined Maj. Patrick Ferguson briefly to help recruit and train local Tories.[6] But after the British/Loyalist disaster at King’s Mountain, S.C., where Ferguson was killed, he moved to Chatham County and laid low. When the British army occupied Hillsborough in 1781, he returned to activity, fortifying a base camp near today’s Ramseur after the British retreat to Wilmington. His militia began a yearlong campaign of mutual terror against Patriots. He wrote Patriot Gov. Thomas Burke: “‘I will retaliate blood for blood and tenfold for one and there shall never an officer or private of the rebel party escape that falls into my hands hereafter but what shall suffer the pain and punishment of instant death.’”[7] Over time he built up an army of more than 900 men. Among his exploits were the capture of dozens of Chatham County officials near the courthouse, kidnapping of the Patriot governor, two wins in open battle with Whig forces, and numerous attacks on individual Patriot homes. In April 1782, he escaped to British-controlled Charleston and eventually moved to Nova Scotia. There he served in, but was kicked out of, its Provincial Congress; was convicted of rape but pardoned; became a mill owner and ship builder; and died at age 69.

David Fanning was not yet born when in 1755 his father, a landowning farmer in Virginia, drowned in the Deep River while looking for land in Orange County.[1] His mother moved them to what now is Wake County, but died when he was 8. Fanning eventually became a ward of a county justice in today’s Smithfield. He was treated mostly as a worker and otherwise neglected, but learned outdoor skills, horsemanship, and to read. He developed a scalp disease, likely eczema, that may have caused some baldness and led him to wear a wig in later years.[2] He first served in the militia at 16, and left home a year later. Fanning was taken in by a kinder family in Orange County for a period, and the wife cured his scalp issue. Fanning did carpentry for them and gained a reputation as a horse tamer. Eventually he moved to Upstate South Carolina, learned to trade goods with Native Americans[3], and became a farmer. He joined local Loyalist (“Tory”) militia in May 1775 that suppressed early rebels (“Whigs”). For three years Fanning fought alongside the Cherokees during their attacks on the frontier, led Loyalist units, or was in jail: He claimed he was captured 14 times, either escaping or being released each time.[4] He also rode briefly with an infamous N.C. robber, “Plundering Sam” Brown.[5] In August 1779 he took a parole from the South Carolina governor on condition of serving with the Patriots, which he did until the British captured Charleston the next May. He then returned to the King’s cause. The next month he joined Maj. Patrick Ferguson briefly to help recruit and train local Tories.[6] But after the British/Loyalist disaster at King’s Mountain, S.C., where Ferguson was killed, he moved to Chatham County and laid low. When the British army occupied Hillsborough in 1781, he returned to activity, fortifying a base camp near today’s Ramseur after the British retreat to Wilmington. His militia began a yearlong campaign of mutual terror against Patriots. He wrote Patriot Gov. Thomas Burke: “‘I will retaliate blood for blood and tenfold for one and there shall never an officer or private of the rebel party escape that falls into my hands hereafter but what shall suffer the pain and punishment of instant death.’”[7] Over time he built up an army of more than 900 men. Among his exploits were the capture of dozens of Chatham County officials near the courthouse, kidnapping of the Patriot governor, two wins in open battle with Whig forces, and numerous attacks on individual Patriot homes. In April 1782, he escaped to British-controlled Charleston and eventually moved to Nova Scotia. There he served in, but was kicked out of, its Provincial Congress; was convicted of rape but pardoned; became a mill owner and ship builder; and died at age 69.

More Information

- Butler, Lindley, ‘Fanning, David’, NCpedia, 1986 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/fanning-david> [accessed 7 April 2020]

- Caruthers, E. W., Revolutionary Incidents and Sketches of Character, Chiefly in the ‘Old North State’ (Philadelphia, Hayes & Zell, 1854) <http://archive.org/details/revolutionaryinc00caru> [accessed 17 April 2020]

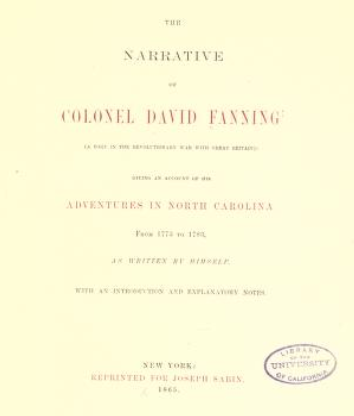

- Fanning, David, The Narrative of Colonel David Fanning (New York, NY: Reprinted for Joseph Sabin, 1865) <https://archive.org/details/toryintherevolu00fannrich/page/n8/mode/2up>

- Hairr, John, Colonel David Fanning: The Adventures of a Carolina Loyalist (Averasboro Press, 2000)

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Colonel David Fanning’, The Loyalist Leaders in North Carolina, 2012 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/loyalist_leaders_nc_david_fanning.html> [accessed 7 April 2020]

- Mayr, Gregory, ‘“Blood for Blood”: David Fanning and Retaliatory Violence between Tories and Whigs in the Revolutionary Carolinas’ (Kansas State University, 2014)

- Parker, Hershel, ‘The Memorial of David Fanning’, Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution, August 2015 <http://www.southerncampaign.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/SCAR-Vol-10-No-4.1.pdf> [accessed 7 April 2020]

- Sherman, Wm. Thomas, Calendar and Record of the Revolutionary War in the South: 1780-1781, Tenth Edition (Seattle, WA: Gun Jones Publishing, 2007) <https://www.americanrevolution.org/calendar_south_10_ed_update_2017.pdf>

[1] Hairr 2000.

[2] Hairr, who says a story that Fanning became completely bald for life is probably wrong, only reported by a mid-1800s source third-hand (Caruthers 1854).

[3] Hairr.

[4] Fanning 1865.

[5] Hairr.

[6] Sherman 2007.

[7] Mayr 2014.