Patriots Block a Tory Army

Location

Type: Hidden History

County: Cumberland

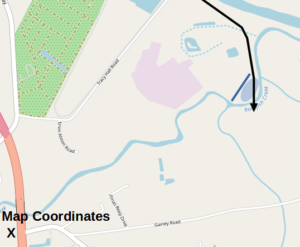

Moore’s campsite is on land owned by the Fayetteville Public Works Commission, behind the Rockfish Creek Water Reclamation Plant, in a secure area not open to the public. The map points toward the closest spot the public can get to the site along the creek by car. If you visit, park on the solid shoulder off Highway 87 across from Butler Nursery Road (coordinates: 34.9548, -78.8447).

Description

Six months before the Declaration of Independence was signed, the British government had already lost control of the Province of North Carolina. Royal Gov. Josiah Martin had been chased out of New Bern and was living on a ship off the mouth of the Cape Fear River. At Martin’s suggestion, two British armies were converging there by sea to take it back, and Martin called for loyal volunteers to join them.

Nearly 1,600 men gathered in Cross Creek (modern Fayetteville) in February of 1776 under command of a British Army officer, Brig. Gen. Donald MacDonald. They prepared to march toward Brunswick Town, which is on this side of the Cape Fear River near modern Southport. However, Patriots (“Whigs”) had intercepted Martin’s January message to Loyalists, and were converging from across the state to foil Martin’s plans.

The most direct route to Brunswick Town crossed Rockfish Creek near the river, using a wooden bridge.[1] A force of 1,000 men, backed by five cannons, camped there under the command of Col. James Moore from Thursday, February 15, to the 21st, to block the Tories’ path.

The men built a breastwork across a downward bend in the creek—a bad mistake, showing their officers’ lack of experience. If the Tories attacked and the Patriot line was broken, the defenders would have been trapped against a deep creek valley with only the bridge for escape!

On Monday the 19th, a messenger arrived from MacDonald carrying a flag of truce. The Tory recruits had moved within four miles. MacDonald included copies of the call from Martin to create Loyalist militias, and MacDonald’s own order assuring those who joined that their families would be protected. His message said he assumed the Patriot soldiers had not seen them, because otherwise they would have joined the Loyalists! He gave Moore until noon the next day to do so, and if not, MacDonald said he would take “‘the necessary steps for the support of regal authority.’”[2]

Moore, stalling for time while Whig forces gathered, sent back a vaguely negative response, but said he would consult with his officers. At the appointed time the next day, he declined, also suggestively including a copy of the oath of allegiance to the Continental Congress. MacDonald, expecting that response, had prepared his troops to withdraw immediately. They went back to Campbelltown (also now part of Fayetteville) to cross the Cape Fear there. He hoped to circle by way of Wilmington to Brunswick Town, thus avoiding the Whigs.

Learning of this the next day, Moore marched south in the direction you are facing to block the crossing at Elizabethtown. After another militia unit claimed MacDonald’s next-best route, he took the road that led the Loyalists to defeat at Moore’s Creek Bridge on February 27. Moore’s force arrived too late to participate, other than helping to capture the scattering Tories. But the delay it caused here contributed greatly to that victory by allowing time for the Patriots to collect more troops.

Unlike the ordered rows of tents in regular army camps, in Moore’s camp you would have seen men in everyday clothes spread out within the bend of the creek. They slept in the open in the cold weather for six days to defend their new independence. Somewhere their horses were tied off; these were not cavalrymen, but they traveled on horseback.

Five years later the British Army of Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis marched across the bridge coming from Cross Creek, seeking the safety of the British garrison at Wilmington to recover from the Battle of Guilford Court House. The procession on Sunday, April 1, 1780, would have taken around six hours. Many wounded were in the wagons that passed by.

What Remains

The Patriot breastwork still exists, likely the best-preserved American Revolution fortification in North Carolina.[3] It runs in a straight diagonal line most of the way across the tongue of land within the bend. The angle connected the upper and lower parts of the bend with enough room for 1,000 men behind it. There is no break in the earthwork, and it appears to end before reaching the upper part of the creek. So the road must have run past that end and down the creek to the bridge somewhere along the bottom of the bend, as a 1904 source suggests.[4]

The only road trace found in the vicinity, though old, seems too narrow to allow wagons to pass by each other as was true of “highways” of the time, and is not as deep (worn down) as most other surviving roadbeds from that era. However, it parallels the earthwork to the north, so it could be the Brunswick Town Road. No map from the era provides enough detail to be sure of the route or bridge location.[5]

[1] Rankin, Hugh F., ‘The Moore’s Creek Bridge Campaign, 1776’, The North Carolina Historical Review, 30.1 (1953), 23–60.

[2] Ibid.

[3] AmRevNC is grateful to the Fayetteville Public Works Commission for permitting our April 2022 search, and Operations Supervisor Scott McCoy for assisting.

[4] The North Carolina Booklet, Vol. III, No. 12 (Raleigh, N.C.: E.M. Uzzell & Co., Printers and Binders, April 1904). See also: Oates, John A., The Story of Fayetteville and the Upper Cape Fear (Fayetteville, N.C.: Woman’s Club of Fayetteville, 1950) <https://archive.org/details/storyoffayettevi00john>.

[5] In addition to the other footnoted sources, “Stop” information comes from one of two guidebooks; NCpedia; the online essay for the relevant North Carolina Highway Marker; and related Sight pages (see “About Sources“).