The British Run into a Hornet’s Nest

Context

After losing a major battle to the British at Camden, S.C., Continental Army survivors regrouped in Charlotte and marched north to Salisbury, leaving part-time “militia” soldiers to guard this area.

After losing a major battle to the British at Camden, S.C., Continental Army survivors regrouped in Charlotte and marched north to Salisbury, leaving part-time “militia” soldiers to guard this area.

Situation

British

Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis’ British army of 2,300, including Loyalist militia, is approaching the small village of Charlotte. There he plans to use the plentiful local mills to replenish his supplies, before pushing farther into the state.[a]

Continental/Patriot

After harassing the British in the Waxhaws, just south of the border, Brig. Gen. William Davidson withdrew most of his militia forces toward Salisbury. He leaves a unit of 150-200 men under Col. William Davie in Charlotte as a rear guard.

Dates

Tuesday, September 26–Wednesday, December 20, 1780.

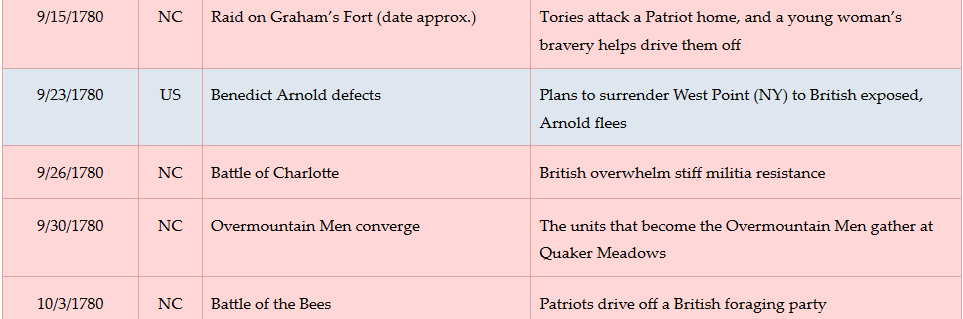

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

The Battlefield

Sources differ on specifics of this battle. Where they conflict, this page defers to the memoir of Capt. Joseph Graham, a Patriot officer during the battle who left the most detailed eyewitness account.

Walk to the east corner of Trade and Fourth streets (down Trade from Independence Square). Look uphill toward the intersection of Trade and Tryon.

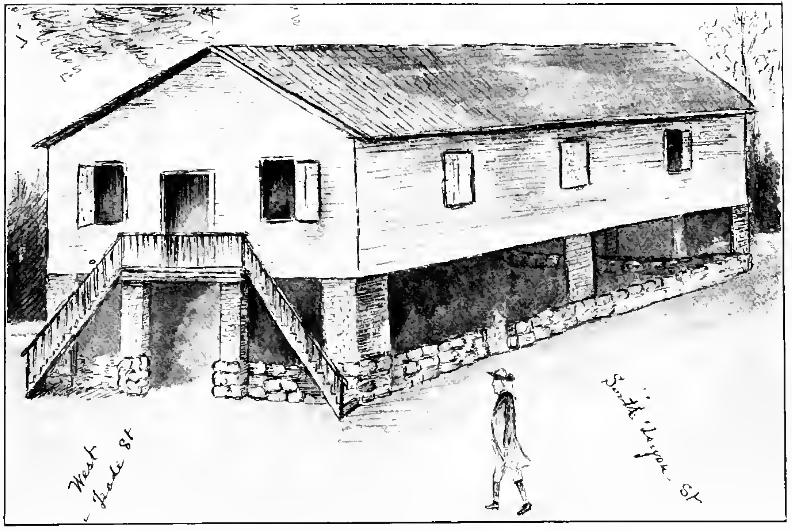

“Charlotte, situated on a rising ground, contains about twenty houses, built on two streets, which cross each other at right angles, at the intersection of which stands a courthouse.” That’s how Col. Davie described the scene in front of you in September of 1780.[1] The wooden courthouse is in the middle of the intersection, raised 10 feet off the ground by 8-10 brick columns. Between the columns along the outside is a stone wall 3-½ feet tall.

This building is where a group of leading citizens draft and, on Thursday, May 31, 1775, sign the Mecklenburg Resolves. More specifically they state that because King George III declared the colonies to be “in a state of actual rebellion” in an address to Parliament, “we conceive that all laws and commissions confirmed by or derived from the authority of the King and Parliament are annulled… and the former civil constitution of these colonies for the present wholly suspended.” It was the first such proclamation on the continent to deny England’s control over the colonies and place governmental power with the Provincial Assembly. However, it stopped short of declaring permanent independence.[2]

You can see the whole town from here in 1780. On Tuesday, September 26, civilians have made themselves scarce in fear of the approach of the British army. Patriot militia soldiers have taken up positions facing in your direction. One line is “twenty steps” in front of the courthouse[3] (around the near edge of Liberty Park and Independence Square). They take cover behind houses, fences, and outbuildings on either side of the wide dirt road. Two more lines are behind the courthouse, but the groundswell and buildings block them from view. Twenty men are sent forward and place themselves behind a house next to you.

Turn around and look roughly three blocks down Tryon.

In the distance, a red dot slowly grows into the front rank of the red-coated British infantry and then halts. A green-coated cavalry unit under Major George Hangar moves to the front and into Tryon (around The Green and museums of today). This is the infamous Lt. Co. Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion, but Tarleton is recovering from two weeks of yellow fever or malaria and had to turn over command temporarily. (Cornwallis had delayed the invasion until Tarleton regained consciousness three days earlier, and Tarleton is traveling here in a litter slung between two horses.[4])

On an order from Hangar, the cavalry begins trotting toward you. The men just behind you fire at them, probably when they are within 100 yards (around Third Street, which did not exist then). Now Hangar orders a charge. They pick up to a full gallop, waving their swords in the air, expecting the militia to run. The men near you likely melt into the woods nearby.

The front line under Col. Davie, with unusual discipline for militia, steps back to the courthouse wall and lets loose a volley when the cavalry is about halfway between you and them (around the state historical marker on the right). The horsemen, surprised, turn aside in disarray. Several wounded horses writhe on the roadway. The Patriot front line then splits off to the sides to go around the second line, which is moving up.

Look back toward the British infantry.

The Redcoat infantry is dividing into two columns. They spread about half a modern block to either side of Trade, wide enough to go around the houses, and march forward.

More Militia Surprises

Walk up to Trade and Tryon at Independence Square.

Hangar, seeing the front line disappear, assumes the militia are retreating, which militia often did in battle. As you watch, the cavalry attacks up the road a second time. When they get to Trade Street, they receive a second volley from men in both directions along the street, and fall back in confusion.

Hangar, seeing the front line disappear, assumes the militia are retreating, which militia often did in battle. As you watch, the cavalry attacks up the road a second time. When they get to Trade Street, they receive a second volley from men in both directions along the street, and fall back in confusion.

As they retreat, the second line of militia advances to Trade, some men going underneath the courthouse behind the wall and the others around. They fire another volley into the British backsides, though their targets are too far away by that time for this to have much effect. The men from the first line join the second, while the British cavalry turns around.

However, the Redcoat infantry is approaching behind the houses and begins to fire on the Patriot flanks, as the cavalry slowly advances again about 100 yards behind. Davie orders the front lines to retreat. They fall in with the third line 100 yards back around modern Fifth Street (also not there at the time).

Cornwallis himself rides into the area and yells to the cavalry, “Legion, remember you have everything to lose, but nothing to gain,” apparently referring to their reputation. They attack past you, splitting around the courthouse, but a volley from Davie’s third line breaks the charge yet again and sends the horsemen wheeling off between the houses on either side.

The infantry is nearing Trade Street behind the houses. The Patriots manage another volley, but they are in danger of being flanked. Davie orders his men to disperse into the woods to your left. Others move up Tryon, which becomes the Salisbury Road north of town, protected by Col. Joseph Graham’s rear guard.

To see how the battle ends, visit the nearby Sugar Creek and George Locke stops.

In Independence Square, you can see the round bronze marker that for decades marked the courthouse location in the middle of the intersection. Nearby is a marker for the controversial Mecklenburg Declaration and the Resolves (see Footnote 2).

After the Battle

Cornwallis’ Camp

Cross Trade Street and turn right. As you walk, look down for a marker in the sidewalk for the site of the Thomas Polk home.

Cross Trade Street and turn right. As you walk, look down for a marker in the sidewalk for the site of the Thomas Polk home.

Cornwallis’s army settles into an encampment surrounding the village. He takes over the house of Thomas Polk, a founder of Charlotte who has made himself scarce, as his headquarters. Including militia and camp followers, around 4,000 people—more than three times the amount in the state’s largest city at the time, Wilmington—spread out as far as you can see in all four directions, many building “brush huts” for shelter.[b]

Cornwallis’s army settles into an encampment surrounding the village. He takes over the house of Thomas Polk, a founder of Charlotte who has made himself scarce, as his headquarters. Including militia and camp followers, around 4,000 people—more than three times the amount in the state’s largest city at the time, Wilmington—spread out as far as you can see in all four directions, many building “brush huts” for shelter.[b]

Cornwallis regularly sends out foraging parties, including many free blacks and escaped slaves, to load up supplies. At Polk’s Mill they find 25,000 pounds of flour, according to a lieutenant.[A] But the foragers are constantly harassed by local militia (see the Battle of the Bees for an example). To “protect the foraging parties and cattle-drivers” Lord Rawdon takes half the army out one day, and Colonel James Webster the other half the next, a British officer wrote.[5] Even within the camp, sentries are subject to Patriot sniping.[c]

Along with the army is Royal Gov. Josiah Martin, run out of the state (still a “province” to him) in 1776. He uses a traveling printing press to issue a proclamation on October 3 informing citizens that, “‘His Majesty moved by… the most tender and paternal of concern, and regard for the misery and sufferings of his people, under the intolerable yoke of arbitrary power… imposed by the tyranny of the rebel Congress upon his freeborn subjects, hath been pleased to send an army to their aid and relief.’” He calls for able-bodied men to join them and sends riders throughout the state with copies, to little results. In part that is because Patriot militia surrounding the town captured many of the messengers.[6]

On October 7, a large Patriot militia force surprises and destroys a British/Loyalist army of 900 on King’s Mountain across the border in South Carolina. Cornwallis, feeling exposed, retreats back the way he came to Winnsboro, S.C., on Thursday, October 12. A town resident claims to hear Cornwallis say as he readies to leave, “Let’s get out of here; this place is a damned hornet’s nest.”

The term, possibly inspired by the Battle of the Bees, is taken up proudly by area residents. It is reflected in the city’s crest and in the name of its professional basketball team, the Hornets.

A Continental Camp

Drift toward the intersection close enough that you can see to the right up Tryon, but look back toward Polk’s house.

After the army’s harrowing defeat to Cornwallis at Camden that led to this invasion, the Continental commander, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, arrives at the Polk house around 11 p.m. on the evening of the battle, August 16. He and a few aides have made a cowardly personal retreat directly from the battlefield without the remains of his army. Gates had ridden 70 miles since that morning, likely changing horses at least once. According to Graham, he stops outside Polk’s house and speaks to him for a few minutes, telling his version of events, without getting off his horse. Then his group rides past you up Tryon Street toward Salisbury and from there all the way to Hillsborough, a two-hour drive by car today![7]

After the army’s harrowing defeat to Cornwallis at Camden that led to this invasion, the Continental commander, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, arrives at the Polk house around 11 p.m. on the evening of the battle, August 16. He and a few aides have made a cowardly personal retreat directly from the battlefield without the remains of his army. Gates had ridden 70 miles since that morning, likely changing horses at least once. According to Graham, he stops outside Polk’s house and speaks to him for a few minutes, telling his version of events, without getting off his horse. Then his group rides past you up Tryon Street toward Salisbury and from there all the way to Hillsborough, a two-hour drive by car today![7]

The next day troops began to arrive from the battlefield, and the village around you is crowded with disoriented soldiers and disorganized local militia. However, the soldiers slowly filter through and then up the Salisbury Road.

Upon reorganizing what is left of the army in Hillsborough, Gates brings it back to Charlotte down the Salisbury Road two months after Cornwallis departs, on Monday, November 20, 1780. The army settles into Cornwallis’ old campsite. After a five-day excursion to a camp about 10 miles south, using today’s Providence Road, it returns and builds winter huts similar to the famous ones at Valley Forge, Penn.[8] A Patriot officer wrote, “‘The dividend of blankets was very inadequate to the occasion.’”[d]

Upon reorganizing what is left of the army in Hillsborough, Gates brings it back to Charlotte down the Salisbury Road two months after Cornwallis departs, on Monday, November 20, 1780. The army settles into Cornwallis’ old campsite. After a five-day excursion to a camp about 10 miles south, using today’s Providence Road, it returns and builds winter huts similar to the famous ones at Valley Forge, Penn.[8] A Patriot officer wrote, “‘The dividend of blankets was very inadequate to the occasion.’”[d]

On Saturday, December 2, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene enters town down Tryon and shelters with Polk. “At this time, Greene was thirty-eight years old, somewhat corpulent, but taller than the average man and of a fair complexion,” an historian writes. “An old injury had left him with a limp.”[e] Greene kept Polk up almost all night interviewing him. Polk said later Greene “‘better understood (the supply problem) than Gates had done in the whole period of his command.’”[f]

Within a few days Greene takes command from Gates, making the courthouse his headquarters. Gates’ trials are not supposed to be over. Greene has orders from Gen. George Washington to open a “board of inquiry” into Gates’ conduct at Camden. Whether due to a lack of high-ranking officers for the board or mere reluctance, Greene never does, and Gates heads north within a week.[g]

Greene learns that of 1,482 to 2,300 men in the vicinity and well enough to fight, at most two-thirds are Continental regulars instead of militia. Those well-clothed and -equipped only amount to 800.[9] Many he describes as “literally naked,” and he issues orders those men are not to be sent out on guard duty. There is only enough food on hand to feed the army for three days, and the surrounding area has been picked clean.

The enlistments of Col. Davie’s troops have all run out. Since Davie has no one to command, Greene asks him to take over as the quartermaster (in charge of supplying the army). Davie, writing later in the third person, says he turned it down by telling Greene “‘he knew nothing about money or account (so) that he must therefore be unfit for such an appointment…’

“‘The General replied that as to Money and accounts the Colonel would be troubled with neither, that there was not a single dollar in the military chest nor any prospect of obtaining any…’”[10]

Meanwhile, Greene begins to re-establish discipline. “The men were soon given to understand that orders were to be obeyed, camps were to be policed, and uniforms and equipment, however shabby, were to be neat and clean,” an historian writes. A deserter was hung the week after Greene took over, with the whole army ordered out to watch.[h]

In the courthouse around that time, Greene and his officers decide to split the army. Greene hopes to obtain more food for both wings, pin down Cornwallis, and provide rallying points for Patriot militia. On Wednesday, December 20, most of the troops move southeast toward what now is Cheraw, S.C. Along with them go the entire Catawba nation of 300 people, allies of the Patriots, including about 60 warriors.[i] Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan leads 300 soldiers and additional cavalry to the northwest on Trade St., heading toward the Catawba River with plans to meet up with more militia troops.

Battle Map

The Battle of Charlotte: Line locations are approximate. 1) British approach as Patriot militia wait in three main lines with pickets in front. 2) British cavalry attack, as Patriot front line withdraws to courthouse (dotted blue line) and fires, pushing them back. Patriots retire around advancing second line. 3) British infantry form lines and march behind houses. 4) Again the cavalry attacks, but is caught in crossfire from units hidden on Trade and retreats; militia second line goes to courthouse and fires. 5) Redcoat flanking fire forces Patriots to retreat. 6) Patriot reserves fire two volleys and begin rear-guard action.

Casualties

Historical Tidbits

- The intersection of Trade and Tryon was a crossroads for centuries, perhaps millennia, before the battle. Tryon Street started as the Great Warriors Path or Trading Path, which ran from modern Pennsylvania to Georgia. It later became the Great Wagon Road that brought many colonists from the north. Trade Street was the Tuckaseegee Trail, a Native American trading path from the coast to the mountains via Tuckaseegee Ford over the Catawba River. Though both routes were used by Native Americans, they were probably blazed by migrating animals! (The ford was at today’s U.S. National Whitewater Center. The trail went across part of the river to the north tip of Sadler Island, continued about halfway down the west edge, and then crossed the rest of the river northwest to the point now occupied by a marina.[11])

- In 1700, Englishman John Lawson made an epic exploration of the Carolina colony, mostly on foot in an arc from Charleston to Washington, N.C. He spent the night in a Catawba Indian town surrounding this intersection.[12]

More Information

- Anderson, William, ‘Camp New Providence’ (EleHistory Research, 2011) <http://elehistory.com/> [accessed 22 March 2020]

- Anderson, William, ‘Where Did Cornwallis’s Army Invade North Carolina?’ (EleHistory Research, 2009) <http://elehistory.com/> [accessed 10 July 2020]

- Ashe, Samuel A. (Samuel A’Court), History of North Carolina (Greensboro, NC: C.L. Van Noppen, 1908) <http://archive.org/details/historyofnorthca01ashe> [accessed 28 May 2021]

- Butler, Lindley, North Carolina and the Coming of the Revolution, 1763-1776 (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1976)

-

Gordon, William, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independence of the United States of America: (New-York: Printed for Samuel Campbell, no. 124, Pearl-street, by John Woods, 1802) <http://archive.org/details/historyofrise03gord> [accessed 22 January 2022]

- Graham, William A. (William Alexander), General Joseph Graham and His Papers on North Carolina Revolutionary History (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton, 1904) <http://archive.org/details/cu31924032738233> [accessed 27 March 2020]

- Greene, George Washington, The Life of Nathanael Greene: Major-General in the Army of the Revolution (G. P. Putnam and Son, 1871), Google-Books-ID: lHRKAAAAYAAJ

- Hill, Michael, ‘Mecklenburg Resolves’, NCpedia, 2015 <https://www.ncpedia.org/mecklenburg-resolves> [accessed 23 April 2020]

- Huler, S. (2019), A Delicious Country: Rediscovering the Carolinas along the Route of John Lawson’s 1700 Expedition. The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill.

- Jones, Randell, Before They Were Heroes at King’s Mountain, North Carolina/Tennessee Edition (Winston-Salem, NC: Daniel Boone Footsteps, 2011)

- Lewis, J.D., ‘Charlotte’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2014 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_charlotte.html> [accessed 24 December 2019]

- MacKenzie, Roderick, Strictures on Lt. Col. Tarleton’s History ‘of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America’ (London: Printed for the Author, 1787).

- Morrill, Dan L., ‘Independence and Revolution’, A History Of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County <http://www.cmhpf.org/morrill%20book/CH2.htm> [accessed 23 December 2019]

- Norris, David, and Daniel Barefoot, ‘Charlotte, Battle Of’, NCpedia, 2006 <https://www.ncpedia.org/charlotte-battle> [accessed 23 December 2019]

- Pancake, John S., This Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas, 1780-1782 (University, AL : University of Alabama Press, 1985) <http://archive.org/details/thisdestructivew00panc> [accessed 13 October 2020]

- Parramore, Tom and Barbara, Did the American Revolution Begin in North Carolina? (Raleigh, N.C.: Office of Publications, School of Education, NCSU, 1973)

- Ramsey, Emily, The Tuckaseegee Ford and Trail (Charlotte, NC: The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, 2017) <http://landmarkscommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Tuckaseegee-Ford-Trail.pdf> [accessed 8 July 2020]

- Rankin, Hugh F., ‘Polk, Thomas’, NCpedia, 1994 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/polk-thomas> [accessed 1 July 2020]

- Rankin, Hugh F., The North Carolina Continentals (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1971)

- Robinson, Blackwell, The Revolutionary War Sketches of William R. Davie (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1976)

- Rumple, Jethro. 1916. A History of Rowan County, North Carolina : Salisbury, N.C. : Republished by the Elizabeth Maxwell Steele Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution. http://archive.org/details/historyofrowanco00rump.

- Sherman, Wm. Thomas, Calendar and Record of the Revolutionary War in the South: 1780-1781, Tenth Edition (Seattle, WA: Gun Jones Publishing, 2007) <https://www.americanrevolution.org/calendar_south_10_ed_update_2017.pdf>

- Stedman, C., Patrick Byrne, and Patrick Wogan, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War (Dublin: Printed for Messrs. P. Wogan, P. Byrne, J. Moore, and W. Jones, 1794), i <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100584349> [accessed 31 January 2022]

- ‘The Charlotte Town Resolves; May 31, 1775’, Avalon Project <https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/charlott.asp> [accessed 23 April 2020]

[1] Robinson 1976.

[2] Quoted from Butler. Some in Mecklenburg County believe there was an earlier “Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence,” and its purported date appears on the North Carolina flag. Unfortunately, unlike the Resolves, the “Meck Dec” was not referenced in government records or periodicals of the day, and no copy exists. The first evidence was reconstructed from memory nearly 30 years later. After a detailed accounting of the evidence for and against in 1908, historian Samuel A. Ashe pointed out that none of the affidavits produced in the early 1800s by participants mentioned two meetings. He, most modern professional histories, and the State Library of NC consider the claim a misremembering of the Resolves. See the library’s “NCpedia” debunking of the Meck Dec for details.

[3] Graham 1904.

[4] Jones 2011.

[5] Stedman 1794.

[6] Graham; capture of messengers, Pancake 1971.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Anderson 2011.

[9] Greene 1871; Rankin 1971.

[10] Robinson 1976.

[11] Ramsey 2017.

[12] Huler 2019.

[a] Sources from the time including Cornwallis’ letters suggest he was undecided what direction to take from there. Possible destinations included Salisbury, today’s Fayetteville (Sherman 2007), Hillsborough, and the lead mines of Virginia, a source of material for making bullets.

[b] Huts: Rankin 1971.

[c] Rankin.

[d] Quoted in Sherman 2007.

[e] Rankin.

[f] Quoted in Pancake 1985.

[g] Sherman 2007. Sherman cites sources from the time giving dates for the formal change of command ranging from the 3rd to the 6th.

[h] Pancake.

[i] Gordon 1802.

[A] MacKenzie 1787.