A Royal Palace and a Tragic Death

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.1069, -77.0443.

Type: Sight

Tour: Cape Fear

County: Craven

![]() Full

Full

Park anywhere near the coordinates, at the outer gate to Tryon Palace. There are parking lots down the street along its west side (to the right from the front), and at the related North Carolina History Center on the east near the river.

You do not need a ticket to walk the grounds when open. But a tour of the palace is a wonderful step back into colonial and Revolutionary history. The ticket office is on the northeast corner of the intersection in front of the gate.

Our tour is fully wheelchair accessible, and most of the route can be driven. Check the Tryon Palace website for limitations in its buildings.

Context

New Bern effectively became the capital of the Province of North Carolina when the royal governor moved here from Brunswick Town, south of Wilmington, in 1765.

New Bern effectively became the capital of the Province of North Carolina when the royal governor moved here from Brunswick Town, south of Wilmington, in 1765.

Situations

This page focuses on four colonial or Revolutionary stories:

- In response to increasing violence by western protestors called “the Regulators,” Royal Gov. William Tryon marches volunteer soldiers west to confront them in 1771.

- Tryon’s successor and the legislature come to political blows over conflicts between the assembly and the British Parliament.

- Tensions rise over the attempt to form a Continental Army regiment made up of French immigrants.

- British troops raid the town near the end of the Revolutionary War.

Dates

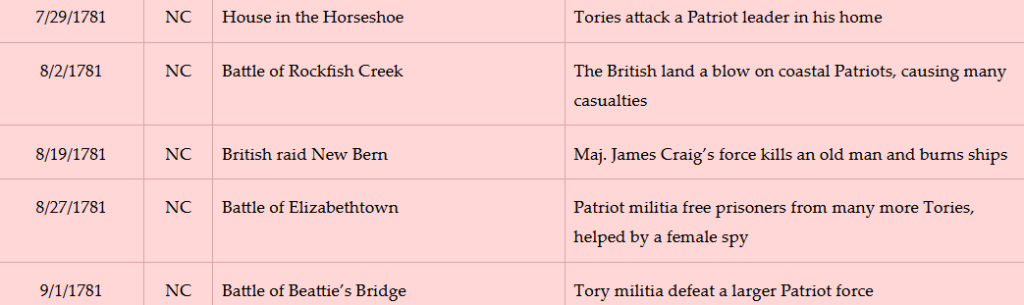

Thursday, November 2, 1769–Sunday, August 19, 1781.

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

A Residence and Symbol

Walk to the inner gate of Tryon Palace. The current building only dates to 1959, but was reconstructed on the exact site of, and using the blueprints for, the original building. Most of the brickwork in the western (right-side) separate wing is original, however.

Look at the palace.

Royal Gov. William Tryon wanted the most beautiful building in the colonies here, to represent the power of the English government, and did not hesitate to spend tax money to get it. The original 40-room palace was finished in 1770 for a total of £15,000,[1] worth $3 million in 2020.[2] The Provincial Assembly (legislature), dominated by rich easterners, approved the budget.

Royal Gov. William Tryon wanted the most beautiful building in the colonies here, to represent the power of the English government, and did not hesitate to spend tax money to get it. The original 40-room palace was finished in 1770 for a total of £15,000,[1] worth $3 million in 2020.[2] The Provincial Assembly (legislature), dominated by rich easterners, approved the budget.

Here the governor lived and worked. The Council of State, royally appointed landowners who doubled as the upper house of the legislature, met with him in a ground-floor ballroom on the left side. (Only the assembly’s lower house was elected. Where it met isn’t known, since no room at the palace was large enough, but several buildings in town were.[3])

The palace’s cost played a role in the rebellion during that time by western colonists calling themselves the “Regulators.” Among their complaints were county officials who embezzled tax money. Another was the province’s law that taxed farmland by the acre, despite the fact eastern lands were more productive than those in the west, and thus earned more money per acre. So anything that seemed to waste provincial funds became a target of the Regulators’ wrath.

Around the time the palace was completed, tensions reached a boil after years of unresolved complaints. The Regulators prevented a court from meeting in Hillsborough and attacked court officials. In the Spring of 1771, Tryon got permission from the assembly to suppress the rebellion using the existing part-time defense forces called “militia.”

In March, Tryon writes letters in the palace to county militia commanders, ordering them to recruit volunteers (see “Tryon’s March” for details). He also writes the commander of British forces in North America, Maj. Gen. Sir Thomas Gage in New York City, for guns and supplies. They arrive at the waterfront by ship in mid-April.

He wrote Gage, “Tuesday the 23rd, the Guns were Landed, and drawn to the Palace by the Militia Men, with all the Pomp We Could Honor them with.”[4] (Companies from two counties had rendezvoused here.) He writes in his campaign journal that the field pieces were followed by a set of flags and six drums. Camp kettles, leggings, and cockades were among the supplies as well.[5] Leggings, often leather, looked like the part of a boot from the knees to the ankle and protected the lower leg. Cockades were hat decorations, usually made of ribbon or feathers, used to differentiate armies and ranks, especially important when both sides had no uniforms. Perhaps the two, small three-pounder cannons—named for the weight of cannonball they fired—were dragged somewhere within your view, and the supplies stored in the stable on your right.

The two companies march west the next day after eleven wagons of flour arrive from Orange County, and four from Rowan. Both counties, much larger then, were centers of the rebellion. Tryon writes about the wagons to Gage and adds with apparent satisfaction, “all which come upwards of 200 Miles from among the Settlements of the Regulators.”[6] The next day he rides past you on a white horse toward the army’s rendezvous point at Smith’s Ferry, today’s Smithfield. (See “Tryon’s March” for what happens next.)

Two months pass. Tryon returns in triumph late in the evening of Monday, June 24, after leading the army to victory at the Battle of Alamance near modern Burlington. The residents wake up, illuminating the town with candle and lantern light, and build a bonfire to welcome him. They celebrate into the night.[7] The next day, a newspaper reports, the “whole Town met in a Body and waited on his Excellency at the Palace with a congratulatory Address, to which he returned a very polite Answer.”[8]

However, near the end of the campaign, Tryon had received word he was to leave immediately for his new post as governor of the Province of New York. Only a year after achieving his dream of living in a beautiful palace, Tryon and his family left it by ship.

The palace remained the seat of government, however, because Tryon’s successor, Royal Gov. Josiah Martin, moved in. His stay was shorter than expected, too. Due to Revolutionary disputes in 1775, a large group including local militia crowds past you onto the circular driveway on Tuesday, May 23. In the lead are several prominent citizens including Dr. Alexander Gaston and Abner Nash. Martin has them shown to a room in the basement and goes to speak with them. They complain about Martin having six cannons behind the palace dismounted that morning, concerned because the Virginia governor had recently taken ammunition from the people there. He claims the old carriages are “rotten” and cannot withstand the guns being fired for the birthday of the king. In reporting this to his boss later, he admits this was partially true, but the citizens were also right! His ruse works, though, and the group leaves.[9]

The palace remained the seat of government, however, because Tryon’s successor, Royal Gov. Josiah Martin, moved in. His stay was shorter than expected, too. Due to Revolutionary disputes in 1775, a large group including local militia crowds past you onto the circular driveway on Tuesday, May 23. In the lead are several prominent citizens including Dr. Alexander Gaston and Abner Nash. Martin has them shown to a room in the basement and goes to speak with them. They complain about Martin having six cannons behind the palace dismounted that morning, concerned because the Virginia governor had recently taken ammunition from the people there. He claims the old carriages are “rotten” and cannot withstand the guns being fired for the birthday of the king. In reporting this to his boss later, he admits this was partially true, but the citizens were also right! His ruse works, though, and the group leaves.[9]

Martin comes out the door with a friend on Wednesday the 31st. He remarks loudly that he is going to visit the chief justice. In fact, he is abandoning New Bern, fearing for his safety. He had already shipped his pregnant wife and children off to his uncle’s care in the New York countryside. “With the aid of a few faithful servants he spiked the cannon and buried all ammunition and military accouterments beneath the cabbage bed in the palace garden.”[10] Martin heads for the Loyalist stronghold of Cross Creek, now Fayetteville, likely taking the long way to Fort Johnston (Southport) to avoid the militant rebels of Wilmington.

Six months pass before another governor arrives in January 1777. This one, Richard Caswell, is newly sworn-in as the first governor of the State of North Carolina. You see him walk into the neglected building for an inspection. Caswell is not pleased by what he finds. He arranges for its clean-up, and the building again becomes the governor’s home and capitol briefly. Shortly after, however, he decides New Bern is too vulnerable to attack, from both the British by sea and smallpox. He moves himself and the state records to Kingston (now Kinston).

Three years later, in 1780, you see enslaved workers tear out lead from the building, so the metal can be turned into musket balls for Patriot guns. This is the last year the state assembly meets in New Bern. Abner Nash, now governor, recommended it meet in Halifax the next January due to a British army newly installed in South Carolina. When a Redcoat corps occupied Wilmington the next year, Nash decided it was “‘prudent to move away,’” making him the last governor to use the palace.[A] The state government would not have a permanent home until Raleigh was built for that purpose after the war.

The ballroom hosted its most famous visitor in 1791, Pres. George Washington, as part of his tour of the southern states. The original palace burned down seven years later except for the right-side wing, by then a school.

Revolutionary Homes

When done at the palace, walk back to the outer gate. Cross Pollock Street, and walk up the left side of George Street, which stretches away from the gate. Stop at the Stanley House a half-block up on the left.

This house was built for the family of John Wright Stanley near the end of the war in the early 1780s, at a later stop on our tour. During the Revolution, Stanley owned a privateer fleet (government-sanctioned pirates), and an import business that provided vital supplies to the Continental armies.

This house was built for the family of John Wright Stanley near the end of the war in the early 1780s, at a later stop on our tour. During the Revolution, Stanley owned a privateer fleet (government-sanctioned pirates), and an import business that provided vital supplies to the Continental armies.

A British corps occupied Wilmington in January 1781. When the main British army in the South under Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis joined it in April, Stanley figured he would become a target. He, his family, and their household goods boarded two ships and fled to Philadelphia. It was a good decision. Their home at the time on Front Street, along with his warehouses, were destroyed by British troops in a raid described below. Making things worse, the ship with the family’s property was caught by British blockaders. The Stanleys came back the next year with the war still on, and moved into another home while this was built at its original location.

Though local tradition holds that Washington stayed in the house during his visit, there is no evidence to support (or deny) this. Washington’s diary does not specify. A war-related story about him visiting a specific tree is untrue.[11]

Continue up George Street.

The house past the Wright home at 313 George existed during the war. John Daves (the correct spelling) may have moved to New Bern with his family from Mecklenburg County, where Charlotte is, at age two, around 1750. One source says that as an adult, he built much of this house personally.[12] He joined the N.C. militia as a soldier in 1775, fighting in early actions in Virginia and then South Carolina. Daves was named quartermaster (supply officer) of the 2nd N.C. Regiment of the regular Continental Army in June 1776, which was ordered north to serve under Gen. Washington. He stayed in the army the rest of the war, fighting in Washington’s northern battles, spending the winter of 1777-8 at Valley Forge, Penn., and getting wounded at the Battle of Stony Point (N.Y.) in 1779. Sent south with the N.C. Continentals to defend Charleston in 1780, he is believed to have been captured there but was released.

The house past the Wright home at 313 George existed during the war. John Daves (the correct spelling) may have moved to New Bern with his family from Mecklenburg County, where Charlotte is, at age two, around 1750. One source says that as an adult, he built much of this house personally.[12] He joined the N.C. militia as a soldier in 1775, fighting in early actions in Virginia and then South Carolina. Daves was named quartermaster (supply officer) of the 2nd N.C. Regiment of the regular Continental Army in June 1776, which was ordered north to serve under Gen. Washington. He stayed in the army the rest of the war, fighting in Washington’s northern battles, spending the winter of 1777-8 at Valley Forge, Penn., and getting wounded at the Battle of Stony Point (N.Y.) in 1779. Sent south with the N.C. Continentals to defend Charleston in 1780, he is believed to have been captured there but was released.

Daves was promoted to captain in 1781, and after the war became a major of state troops. He was appointed the federal customs collector in New Bern, but died in 1804 around age 56. Originally buried in town, his remains were moved to the Guilford Court House battlefield in Greensboro, even though he did not fight there.[13]

Go to the next street, Broad Street. To the left, this became the road to Wilmington then, as it does now. Look in that direction.

Go to the next street, Broad Street. To the left, this became the road to Wilmington then, as it does now. Look in that direction.

On Sunday, August 19, 1781, around 50 British soldiers under Maj. James Craig arrive up the road from Wilmington. Militia had skirmished with him at a bridge crossing the Trent River upstream, probably Webber’s Bridge near today’s Pollacksville, with no success.

You hear scattered potshots from Patriots as the British enter town and the militia leave, too outnumbered to resist. One sniper manages to kill a Loyalist captain somewhere in town.

Angst at the Academy

Turn right, and walk one block to Metcalf Street. Turn left across Broad, and walk one block to New Street. Cross it, and turn right. Walk to the end of the block, to the New Bern Academy Museum on the left.

The 1809 version you see is on or near the spot of the original building begun in 1765, the only school in town during the Revolution.[a] Eyewitness sources for this story differ slightly on details; we defer in those cases to the one more directly involved, Dr. Gaston.[b]

The 1809 version you see is on or near the spot of the original building begun in 1765, the only school in town during the Revolution.[a] Eyewitness sources for this story differ slightly on details; we defer in those cases to the one more directly involved, Dr. Gaston.[b]

After France entered the war on the side of the United States, Frenchmen in the former English colonies sought ways to serve. Chariol de Placer got authorization from the state to create a “French Refugees Regiment” for the Continental Army, with him in command as the colonel. He began seeking soldiers, and the schoolhouse became a barracks for the French unit.

Capt. Charles Biddle told a story in his autobiography about one of the Frenchmen, oddly named O’Neal, who came to town to join the army. O’Neal took a room in the house Biddle lived in. Since Biddle knew a little French, O’Neal latched onto him. “He was one of the most incessant talkers that ever lived,” Biddle complained. Biddle knew Chariol (as records from the day refer to him) and offered to introduce O’Neal. He did so, apparently here, and “made my escape, laughing to think how Chariol… would be plagued with his countryman.” Unfortunately, O’Neal went back that night, woke up Biddle up, and “kept talking to me until I pretended to be asleep.” The next day Chariol found Biddle and said, “Ah! Mr. Biddle! Where you pick up Mr. O’Neal?” Chariol was already tired of the man, but did make him an officer.[B]

Chariol’s efforts are not entirely welcome. The concentration of people speaking another language causes issues for some locals, and shipowners complain of losing sailors to the regiment. Chariol recruited a sailor whom a John Davis said was his “indentured servant,” typically someone who agrees to seven years of personal service in exchange for passage to America. John’s father, James, got an arrest warrant for the sailor. James was a printer who published the state laws for the legislature and N.C.’s first newspaper.

The Davises appear here to claim the sailor on Wednesday, May 27, 1778, with the constable, another son, and one other man. A sergeant comes to the door and refuses them. They argue, and you hear the Davises threaten to come back and take the man by force. Outnumbered for now, however, they finally leave.

The next day the Davises return with about 20 sailors from one of their ships, plus relatives and friends, “armed with Guns, Clubs,” etc. John Davis has a musket with a bayonet. The Davises claim Chariol has “no right to enlist men” (even though he does). James then threatens to come back tonight and “head a party to put every Frenchman to death in town, or drive them out of it.”[c] They leave again, headed for a later stop on our tour.

However, the mob returns that night, carrying clubs. It “surrounded the school house… armed with Cudgels, and beat and abused Chariol’s men.”[d]

The rest of this story is told at the later stop. Tour the museum if you wish.

From Rebellion to Revolution

Continue along New Street across Hancock Street, and go one block to Middle Street. Turn right and walk one block back to Broad. (Most of the next paragraph is not yet on the audio clip.)

The first Craven County Courthouse was in the middle of the intersection here, a typical practice at that time. Gov. Tryon first arrived in New Bern from Brunswick Town on Christmas Eve, 1764, on a tour of the province as the new governor. Two days later, a “‘very elegant BALL’” was held here in his honor in the “‘beautifully illuminated’” courthouse.[D] Locals lobbied to make New Bern, being more central to the colony, the capital. After an armed confrontation in Brunswick over his call to support the hated Stamp Act tax on all paper goods, he agreed.

Parliament later repealed the Stamp Act, but passed a new set of taxes on imports including tea. (It was trying to pay for the French & Indian War of the 1750–60s and other colonial costs, which the provinces were refusing to cover.) North Carolina’s Provincial Assembly passes resolutions against the taxes and related laws on Thursday, November 2, 1769. In response, Gov. Tryon dissolves the assembly.

Parliament later repealed the Stamp Act, but passed a new set of taxes on imports including tea. (It was trying to pay for the French & Indian War of the 1750–60s and other colonial costs, which the provinces were refusing to cover.) North Carolina’s Provincial Assembly passes resolutions against the taxes and related laws on Thursday, November 2, 1769. In response, Gov. Tryon dissolves the assembly.

Its speaker, John Harvey, leads members of the lower house here to the courthouse. Sixty-four men cram into the small building and agree to hold an extralegal session starting on Monday. On Tuesday they pass an agreement or “association” not to import any British goods until the issues are resolved. Around town afterwards, “the Sons of Liberty used tar and feathers and a ducking stool to enforce the association.”[14]

By March, all of the taxes are repealed except one on tea. When the Boston Sons of Liberty protest that one a few years later with their famous “Tea Party,” Parliament passes laws to punish the town. In 1774, several colonies asked the others to send representatives to a “Continental Congress” in Philadelphia, to try to work things out with King George III. Gov. Martin refused to convene the North Carolina assembly to do that.

Harvey, still speaker, asked local governments to elect delegates to an unofficial “convention.” Most of the counties and four cities do—sending mostly the same men that are in the official assembly—and 71 convene in town on Friday, August 25, for three days.

One modern source claims the renegade assembly met in the courthouse. (At least two other buildings in town were large enough.[15]) The delegates vote to support a boycott of English goods and send three representatives, including later governor Caswell, to the Continental Congress.

The second convention, only later renamed a “Provincial Congress,” meets somewhere in New Bern again the next April, ignoring Martin’s decree that it is illegal. Adjourning and reconvening as the official Provincial Assembly, since 48 of the 68 assembly members are in the congress[16], they approve the actions of the Continental Congress. An incensed Martin dissolves what turns out to be the last Provincial Assembly!

The John Wright Stanley House was originally on the block directly across Middle, behind the current courthouse, facing Middle.[17] The land was an empty lot when he bought it in 1779.

A Cold Shot and Hot Flames

Walk another block on Middle Street to Pollock Street. Turn left, cross Middle, and backtrack slightly to the outline of the Christ Church building of the Revolutionary years inside the fence. Step near the gap in the wall outline, where the front door was. (The next two paragraphs have not been added to the audio tour yet.)

Christ Church was built here in brick in 1750. In colonial times, the Church of England (or “Anglican” church) was supported by taxes everyone had to pay, and only its preachers could marry people. This became one of the complaints Patriots had against British rule.

In 1775, Rev. James Reed of Christ Church is asked by the rebel Committee of Safety to preach about a day of fasting and prayer declared by the Second Continental Congress in support of Boston rebels in July. Reed refuses, saying it is a well-established custom in the colony that the clergy stays out of politics. He asks for the same liberty members want, “‘at least liberty to be peaceful and quiet and do my duty.’” The committee reacts angrily, saying Reed has a duty “‘to inculcate from the pulpit the… principles of truth and justice, the main props of all civil government.’” It calls for the board members that run the church to fire him. They don’t, but local tradition claims young boys sometimes bang a drum at the door of the church here yelling, “‘Off with his head!’”[e]

Go back to Pollock and turn left. Walk one block, and turn right on Craven Street. Stop at the first parking lot on the right, after 235 Craven.

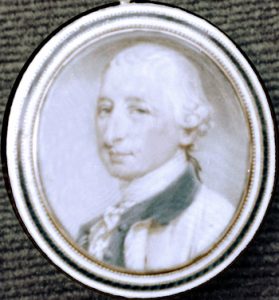

Irish-born Dr. Alexander Gaston, whom we met at the Palace, had been a physician in the British Navy, serving at the Siege of Havana in 1762 during the French & Indian War. After contracting dysentery, he moved to New Bern within three years for his health. His “townhome” was here where the parking lot is now. (Unlike modern townhomes, the word then referred to a plantation owner’s home in town.)

Irish-born Dr. Alexander Gaston, whom we met at the Palace, had been a physician in the British Navy, serving at the Siege of Havana in 1762 during the French & Indian War. After contracting dysentery, he moved to New Bern within three years for his health. His “townhome” was here where the parking lot is now. (Unlike modern townhomes, the word then referred to a plantation owner’s home in town.)

After the 1778 anti-French mob leaves the school house, the Davises lead it here. The county magistrates are meeting on Gaston’s “piazza,” probably meaning his porch. The Davises demand the militia be called to enforce the warrant. Chariol is sent for, and when he arrives, “James Davis (Jr.) clapped his hands on the shoulder of the Col. and told him he was his prisoner…”[f] James, Sr., steps forward as if to slap Chariol, but another colonel blocks him. Davis threatens Chariol with a club, trying to provoke Chariol into responding, but the Frenchman keeps his cool. Chariol agrees to deliver the sergeant and recruit, and the mob breaks up, or so it seems. Instead men with guns roam the town, in part seeking the sergeant, but he has escaped.[g] At some point one of the Davis sons comes to the corner you just passed, yells that the sergeant is gone, and repeats the threat to attack the Frenchmen if he isn’t found.[h]

As you already know, that attack happened. Eventually, it comes out that John has no indenture papers, and merely claims he won the contract from another man. The sailor is freed. The sergeant’s fate is unknown.

In part due to incidents like this, Chariol was unable to gather many troops, and the legislature ended the attempt in August. At Chariol’s request, Gov. Caswell wrote a letter of introduction to Washington for him, saying Chariol was heading to his camp. Then Chariol disappears from history.

John Davis, Jr., was among hundreds of N.C. Continental soldiers who died in captivity after the fall of Charleston two years later, possibly from a whipping on a prison ship.[i]

As Craig’s British force nears in 1781, the elderly Gaston has just finished eating breakfast inside. Somehow hearing of the British approach, he decides to escape back to his plantation directly across the Trent (the river crossing below town). You see him hurry out the front door and down the road in front of you. Moments later his wife Margaret follows, to make sure he is safe, with good reason: The horses’ hooves and militia potshots can be heard nearby.

Follow them down Craven all the way to the river. You will pass through a culdesac at the end of the street and then a covered walkway. Look at the marina.

Follow them down Craven all the way to the river. You will pass through a culdesac at the end of the street and then a covered walkway. Look at the marina.

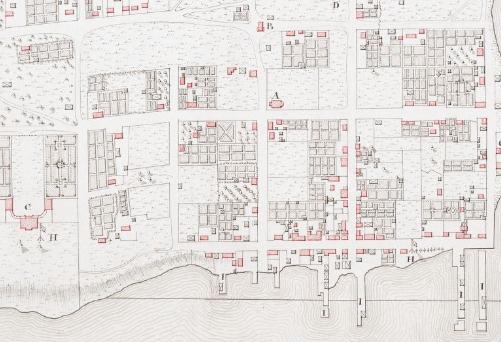

Where pleasure craft and floating homes dock today is the historic waterfront of New Bern in Revolutionary times. Piers of various lengths jut out all along it, starting with two on the far side of the modern bridge to your left, and continuing nearly to the palace out of sight to the right. Here on Saturday, July 4th, 1778, New Bern became only the third city in the new United States to celebrate that date, after Philadelphia and Boston. A ship’s captain writes, “In celebration of this day great numbers of guns have been fired at Stanley’s wharf, and Mr. Ellis’ ship, three different firings from each from early morning, midday, and evening, and liquor given to the populace.”[18]

By 1781, there are cannons along the back side of the palace facing downriver. In the river you see a couple of small “floating batteries,” cannon on rafts near the mouth to your left where the bridge is today, and at least two small naval vessels.

Capt. Biddle commanded an armed merchant ship based here, the Cornelia. “I had six iron guns and 14 wooden ones, and seventy men, not more than five of whom could be called seamen,” he wrote. Wooden “cannons,” shaped and painted like the real thing, were often used to make a ship look more formidable. It worked: During a two-month voyage in the Caribbean, they scared off privateers by thus appearing to have 20 guns![C]

Walk a little to the left, until you are in line with the sterns of the boats along Dock E.

Imagine Craven Street continuing into the river, and just left of its line extends the Old Colony Wharf.[19] (Basically it was in the now-open water behind the boats; on the old map above, it is the third dock from the right.) Gaston runs onto it and climbs into a rowboat that serves as a private ferry. A boy begins pulling for the opposite shore. Within seconds British troopers and Margaret arrive. The boy dives overboard; maybe Gaston tries to take over the oars. Margaret gets between the soldiers and her husband and begs them not to fire. The British captain damns him as a “rebel” and calmly, coolly, takes aim. He shoots Gaston dead in front of his wife.[20]

The British spend the next two days burning plantation homes and, within your view, the cargoes of Patriot owners like Stanly. They destroy 3,000 pounds of salt—a precious commodity in those days—sugar, and perhaps most damaging, barrels of rum! They also burn several ships, and the lines and sails of the rest, before returning to Wilmington.

Casualties

Craig’s Raid, including at Webber’s Bridge:

- British: 4 killed, 5 wounded.

- Patriots: 1 killed, unknown wounded.

Historical Tidbits

- The streets of New Bern were laid out by John Lawson, who traveled by foot from Charleston, S.C., on a 400-mile loop to the area of Washington, N.C., in 1700-1.

- Four blocks north of the palace, the most infamous duel in state history took place 20 years after the war. The eldest son of John Wright Stanley, also John, began verbal and written attacks on Richard Dobbs Spaight after Spaight changed political parties. Spaight was a war veteran who went on to sign the U.S. Constitution and serve as governor. Stanley called Spaight “malicious, low & unmanly”; Spaight responded that Stanley was “both a liar & Scoundrel…” On Sunday, September 5, 1802, at 5:30 p.m., they met behind the Masonic Hall with an audience of 300. In the fourth round of shots, Spaight fell with a wound in his right side. He died a day later. (To see the site, drive up Middle Street past Broad to Johnson Street. Turn right to the duel’s state historical marker, behind the current Masonic Lodge.)

More Information

- Barefoot, Daniel, Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1998)

- Barefoot, Daniel, ‘Tryon Palace’, NCpedia, 2006 <https://www.ncpedia.org/tryon-palace> [accessed 24 October 2020]

- Bell-Kite, Diana, ‘Stanly-Spaight Duel’, NCpedia, 2010 <https://www.ncpedia.org/history/stanly-spaight-duel> [accessed 12 April 2020]

- Biddle, Charles, Autobiography of Charles Biddle, Vice-President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. 1745-1821, ed. by James S. Biddle (Philadelphia, Pa.: E. Claxton and Company, 1883) <http://archive.org/details/autobiographyofc00bidd> [accessed 13 August 2021]

- Butler, Lindley, North Carolina and the Coming of the Revolution, 1763-1776 (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1976)

- Carraway, Gertrude, ‘Daves, John’, NCpedia, 1986 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/daves-john> [accessed 21 December 2020]

- Caswell, Richard, ‘Letter from Richard Caswell to George Washington, Volume 13, Page 231’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1778 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr13-0281> [accessed 13 August 2021]

- Caswell, Richard, ‘Letter from Richard Caswell to Rawlins Lowndes, Volume 13, Pages 119-120’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1778 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr13-0150> [accessed 13 August 2021]

- Cogdell, Richard, ‘Letter from Richard Cogdell to Richard Caswell, Volume 13, Pages 142-143’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1778 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr13-0179> [accessed 30 July 2021]

- Cogdell, Richard, ‘Letter from Richard Cogdell to Richard Caswell, Volume 13, Pages 144-145’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1778 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr13-0179> [accessed 30 July 2021]

- Cross, Jerry, John Wright Stanly House (North Carolina Office of Archives and History, 1987) <https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll6/id/12813> [accessed 28 April 2020]

- Crow, Jeffrey J., A Chronicle of North Carolina During the American Revolution, 1763-1789, North Carolina Bicentennial Pamphlet Series (Raleigh: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1975)

- Cummings, Lindy, Previous Academy Building, E-Mails, 11 August 2021

- Cummings, Lindy, Tryon Palace, Interview and E-mail, 10/20/2020

- Davidson, Chalmers, ‘Hall of Fame: Dr. William Gaston’, (ca. 1960 detached page, publication and date unknown; Courtesy of New Bern Historical Society)

- De Van Massey, Gregory, ‘The British Expedition to Wilmington, North Carolina, January-November, 1781’ (East Carolina University, 1987)

- Dill, Alonzo Thomas, ‘Eighteenth Century New Bern: A History of the Town and Craven County, 1700-1800: Part VII: New Bern During the Revolution’, The North Carolina Historical Review, 23.3 (1946), pp. 325–59

- Dill, Alonzo Thomas, Governor Tryon and His Palace (The University of North Carolina Press, 1955)

- Dunkerly, Robert M., Redcoats on the Cape Fear: The Revolutionary War in Southeastern North Carolina, Revised (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2012)

- Fonvielle, Chris, ‘With Such Great Alacrity’, North Carolina Historical Review, XCIV.2 (2017)

- Ganyard, Robert L., The Emergence of North Carolina’s Revolutionary State Government, North Carolina in the American Revolution (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1978)

- Gaston, Alexander, ‘Deposition of Alexander Gaston Concerning the Actions of James Davis Gaston, Volume 13, Pages 429-430’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1778 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr13-0497> [accessed 13 August 2021]

- Hand, Bill, ‘James Davis and His Ill-Fated Son’, New Bern Sun Journal, 2018 <https://www.newbernsj.com/news/20180218/james-davis-and-his-ill-fated-son> [accessed 14 August 2021]

- Interpreters, Tryon Palace, Tour, 10/8/2020

- Lewis, J.D., ‘New Bern’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2010 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_new_bern_2.html> [accessed 25 January 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘The French Refugees Regiment’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2013 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/nc_french_refugees_regiment.html> [accessed 13 August 2021]

- Mammen, Edwin, ‘North-Carolina Gazette’, NCpedia, 2006 <https://www.ncpedia.org/north-carolina-gazette> [accessed 14 August 2021]

- ‘Marker: C-1’ <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=C-1> [accessed 12 April 2020]

- ‘Marker: C-2’ <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=C-2> [accessed 12 April 2020]

- ‘Marker: C-39’ <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=C-39> [accessed 12 April 2020]

- ‘Marker: C-50’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=C-50> [accessed 6 November 2020]

-

Martin, Josiah, ‘Letter from Josiah Martin to William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth, Volume 10, Pages 41-50’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1775 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0019> [accessed 16 August 2022]

- ‘Minutes of the North Carolina House of Commons North Carolina. General Assembly, April 14, 1778 – May 02, 1778, Volume 12, Pages 655-764’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1778 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr12-0006> [accessed 13 August 2021]

- Powell, William, North Carolina: A History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988)

- Powell, William, ed., The Correspondence of William Tryon and Other Selected Papers (Raleigh, N.C.: Division of Archives and History, Dept. of Cultural Resources, 1980) <http://archive.org/details/correspondenceof1981tryo> [accessed 16 November 2020]

- Rankin, Hugh F., ‘The Moore’s Creek Bridge Campaign, 1776’, The North Carolina Historical Review, 30.1 (1953), 23–60

- Sandbeck, Peter, The Historic Architecture of New Bern and Craven County, North Carolina (New Bern: Tryon Palace Commission, 1988) [via Cummings 2020]

- Staff, New Bern Historical Society, New Bern Locations, Interview and E-mails, 10/2020

- Stumpf, Vernon, ‘Martin, Josiah’, NCpedia, 1991 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/martin-josiah> [accessed 28 April 2020]

- Watson, Alan, A History of New Bern and Craven County (Tryon Palace Commission, 1987)

[1] Barefoot 2006.

[2] Nye, Eric, ‘Currency Converter, Pounds Sterling to Dollars, 1264 to Present’ <https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm>.

[3] Cummings 2020.

[4] Powell 1980.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Essex Gazette (Salem, Mass.), 6/28/71.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Rankin 1953. Other sources say the group finds the cannons and drags them out the gate. That is unlikely, given their weight and location, and inconsistent with Martin’s report in the next paragraph of the text, unless he regained them and didn’t want to admit having lost them (see Martin 1775).

[10] Ibid.

[11] The story claims Washington visited a tree where Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene met area businesspeople to request financial aid during the war. Cummings (2020) reports both that, and the original Greene story, originated with a civic booster more than a century later. Greene’s biography, written by his grandson using Greene’s papers, reports no visit to New Bern or anywhere nearby (Greene, George Washington, The Life of Nathanael Greene: Major-General in the Army of the Revolution [G. P. Putnam and Son, 1871]).

[12] Carraway 1986.

[13] Carraway. War record corroborated by: ‘The Muster Roll Project’, Valley Forge Legacy <http://valleyforgemusterroll.org/index.asp> [accessed 21 December 2020], and ‘United States Rosters of Soldiers and Sailors, 1775-1783’, FamilySearch <https://www.familysearch.org/search/image/index?owc=https://www.familysearch.org/service/cds/recapi/collections/2546162/waypoints> [accessed 13 November 2020]. Mecklenburg, capture, and monument from: ‘John Daves Monument, Guilford Courthouse’, Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina, 2010 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/137/> [accessed 20 February 2021].

[14] Butler 1976.

[15] Powell 1988, without citing his source. Local historians confirmed that no known contemporary sources indicated the location. The first New Bern Academy building had been used by the provincial assembly (Cummings 2020). Christ Church was also big enough, as you can see today in the outdoor chapel built directly above its old foundation at the corner of Middle and Pollock streets. The Third Provincial Congress met in a church in Hillsborough.

[16] Ganyard 1978.

[17] Sandbeck 1988.

[18] Barefoot 1998.

[19] Staff.

[20] Plantation and ferry details, “rebel” comment: Davidson (ca. 1960), from a letter by Gaston’s son, repeating the story as told to him by Margaret.

[a] Cummings 2021.

[b] Gaston 1778.

[c] Cogdell 1778a.

[d] Cogdell.

[e] Watson 1987.

[f] Cogdell.

[g] Ibid.

[h] Gaston.

[i] Hand 2018.

[A] Watson.

[B] Biddle 1883.

[C] Ibid.

[D] Quoted in Watson.

← Beaufort Raid | Cape Fear Tour | Kingston →