Gathering Point for the Overmountain Men

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.7539, -81.7163.

Type: Sight

Tour: Overmountain

County: Burke

![]() Partial

Partial

Turn into the retail lot to the right of Bost Road (coming from Green Street) in Morganton. Drive back near the Bost/Green intersection and park.

This page has three primary stops and two optional ones. There are two at the coordinates, with two possible side trips from there; a nearby cemetery; and the river ford used by the Overmountain Men. All except the graves are either viewable from your vehicle or wheelchair-accessible.

Please see our Hurricane Helene page about likely impacts to this location from the 2024 floods.

Context

British Maj. Patrick Ferguson and his Loyalist army were assigned to repress Patriot activity and protect the flank of the British Army during a foraging campaign to Charlotte in 1780.

British Maj. Patrick Ferguson and his Loyalist army were assigned to repress Patriot activity and protect the flank of the British Army during a foraging campaign to Charlotte in 1780.

Situation

British/Tory

After constant harassment by the North Carolina militia (part-time soldiers) of Col. Isaac Shelby and Col. Charles McDowell in South Carolina, Ferguson chased them as far north as Gilbert Town (near today’s Rutherfordton). He has threatened to follow across the mountains and attack their homes.

Patriot

In response to Ferguson’s threat, militia from around the region are mustering, and McDowell invites them to assemble by his home in Quaker Meadows. Around 1,000 men from as far as Virginia and modern-day Tennessee are coming across the mountains. They split their forces to ensure the two main approaches to their homes were blocked in case Ferguson appeared, among other reasons.

Date

Saturday, September 30, 1780.

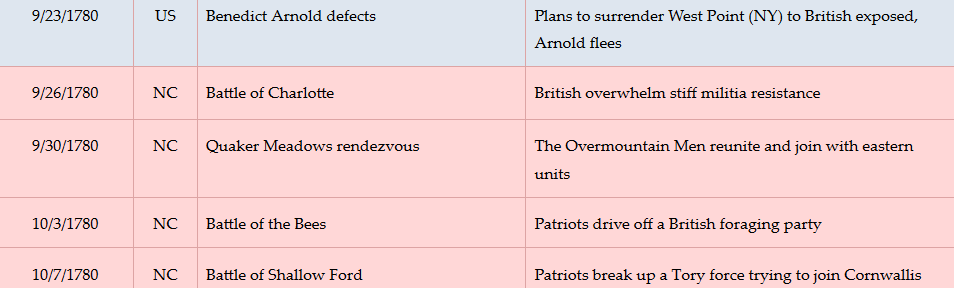

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

The Campsite

“Quaker Meadows” was the name given to the Catawba River flats you are standing on by McDowells’ father, Capt. Joseph McDowell, Sr., borrowed from his prior home in Virginia.

In July 1776, some members of the Cherokee nation attacked European-Americans in the western part of the Carolinas. Two months later Brig. Gen. Griffith Rutherford leads militia forces here on the way to attacking Cherokee villages in response to the raids. They camp in Quaker Meadows and continue toward Davidson’s Fort (now Old Fort, east of Asheville). The Burke County regiment, including McDowell and his brother Joseph, Jr., goes with them.

Four years later, you are standing in either a farm field or an untilled meadow. The McDowell homesite, visited next, is probably behind the far-right end of the modern retail strip.[1] In the evening of Saturday, Sept. 30, 1780, around 480 men arrive up what today is Independence Boulevard (NC 126). These are not regular soldiers, but backwoodsmen, farmers, trappers, and others, both volunteers and members of formal militia units. Most are on horseback, and some are driving beef cows for food. They pour into the meadows and farm fields along both sides of today’s Bost Road and find places to sleep for the night. Sometime afterward, a second group of 360 men arrive by the same route.

These Patriot (“Whig”) militia soldiers set up camp. The meadow is filled with men and horses only: these volunteers have no wagons, tents, cannons, or camp followers to help. They have supplied their own weapons, gunpowder, and bullets, and are carrying any other supplies they can’t hunt along the way. Campfires light up like lightning bugs around you.

Later that night, another 350 men under Col. Benjamin Cleveland arrive from the other side of the meadows after a four-day march from today’s Elkin, probably near or on the route now marked by Bost Road. They are greeted by cheers from the Overmountain Men.[2]

The Council Oak

Look or cross Bost Road to the monument with a tree behind it.

Somewhere near the current tree stood a large oak tree in 1780. (The exact location was already lost by 1914, but compare the background in the picture below to the view to your right.) The next morning all of the leaders meet in the shade of that tree to choose their next steps, perhaps right where you stand. It thus becomes known in later times as the “Council Oak.”

Somewhere near the current tree stood a large oak tree in 1780. (The exact location was already lost by 1914, but compare the background in the picture below to the view to your right.) The next morning all of the leaders meet in the shade of that tree to choose their next steps, perhaps right where you stand. It thus becomes known in later times as the “Council Oak.”

They decide it is most likely Ferguson remains at Gilbert Town. So in hopes of catching him there, they will march their army through the South Mountains and down the Cane Creek Valley to the southwest (the route of today’s US 64). They go back to their camps and order their men to gather their things and mount up. You then see them flow to your right along Green and/or directly into the wagon road at Independence Boulevard, toward Greenlee Ford over the river.

The Return

The Overmountain Men caught their quarry, Ferguson, at King’s Mountain in South Carolina. At Bickerstaff’s Old Fields north of modern Rutherfordton, their commander was passed a rumor that the British cavalry was coming for them. They decamped at 5 a.m. on Sunday, October 15.

Somewhere between 10 p.m. that night and 2 a.m. the next morning, the Patriots and their dwindling number of prisoners drag up the same route by which the Whigs left. They have marched 32 miles on no food. It rained all day. Some of the prisoners collapsed and were trampled underfoot along the way. Given the rains, the leaders had feared the Catawba River would flood and trap them on the other side, vulnerable to attack.

They camp again in Quaker Meadows. Charles McDowell “‘rode along the lines, and informed us the plantation belonged to him, and kindly invited us to take rails from his fences, and make fires to warm and dry us.’”[3]

The next day the victorious militia army disbands. Most of the Overmountain Men and South Carolina troops that came back with them return home. The latter probably have to wait, because the Catawba has indeed flooded by then. This leaves 500–600 men, primarily Cleveland’s men, to escort hundreds of prisoners to Bethabara (in modern Winston-Salem). They march out the way those men first arrived for the campaign, around 2 p.m. Monday.

The number of prisoners is unknown, somewhere between the 600 first captured and the 300 the Moravians report arriving at Bethabara. Some have been paroled, some died, and others are leaking away every day.

McDowell Station

Walk or drive within the same lot you parked in, to the back-left corner of the retail strip.

Walk farther out Bost Road a short distance, to the start of a tall hedge. Step to the right and go behind the hedge, staying within the utility right-of-way to respect property rights. Continue a short distance looking to the right. Stop when you can see a treeless rise in the distance, in front of a higher hill with woods further out.

An archaeologist believes that rise is the likely location of McDowell Station, built by Joseph, Sr.[4] It was near the intersection of the road that now is Independence Boulevard, which at the time extended past Green Street to that point, and one coming off the hill behind you across Bost Road.[5] Joseph, Sr., died in 1771, leaving the house to Charles, and 12 enslaved people each to him and his brother.[6]

An archaeologist believes that rise is the likely location of McDowell Station, built by Joseph, Sr.[4] It was near the intersection of the road that now is Independence Boulevard, which at the time extended past Green Street to that point, and one coming off the hill behind you across Bost Road.[5] Joseph, Sr., died in 1771, leaving the house to Charles, and 12 enslaved people each to him and his brother.[6]

The term “station” implies a home that also served as a trading post and was fortified for protection against attack, with thick walls and perhaps a palisade (wall of vertical logs). Indeed, McDowell Station likely was attacked as part of the 1776 raids. According to a letter written July 14, 1776, by Rutherford, “‘Col. McDowell 10 men more & 120 women & children is (besieged) in sume (sic) kind of a fort, & the Indians Round them…’”[7] Apparently the Cherokees gave up, perhaps fearing other militia would arrive if they stayed too long. As already described, that indeed happens the next month.

When the Overmountain Men return here after King’s Mountain, the British and Loyalist officers among the prisoners are “‘lodged comfortably’” in the house, according to one of them. Their welcome is less than warm, though. Some of them were part of a party that raided the area during Ferguson’s stay in the region, and stole Charles’ and Joseph’s best clothes. Their widowed mother Margaret had warned the officers then that fortunes change, and now is little interested in housing “‘these thieving vagabond Tories.’”

Charles persuades her nonetheless. British surgeon Dr. Uzal Johnson wrote, “We were well entertained and got a good Supper, which we stood in great need of, having eat (sic) nothing all Day but a Raw Turnip which I begged from the Guard.”[a]

Joseph, Jr., also a Patriot militia officer, had his own home on land bequeathed him by his father. It was along Silver Creek on the other side of the river.[8]

Just one block away is Charles’ substantial wedding gift to his son Charles, Jr., in 1812: an unusual brick house you can still visit! See the last “Historical Tidbit” below for directions.

Cherryfields

A roughly 20-minute detour, round-trip, will take you to the homesite where a Patriot woman sacrificed herself for a soldier. Or you can skip to the “Cemetery” section and read this story at her grave, which is nearer.

To see where it happened, return to Bost Road, and:

- Drive about 4.5 miles to the end of Bost at Piedmont Road, and turn left.

- Drive about 2 miles to Henderson Mill Road, and turn left.

- Drive 0.8 miles, and park just before the bridge on the shoulder, or in the pull-out by the creek on the right.

The “Cherryfields” home was on or near the site of the nearest modern house, uphill on this side of the creek.

During the Revolution, when Sarah Robinson Earvin is around 30, she is taking care of a neighbor, Samuel Alexander, a wounded Whig militiaman. Her husband Alexander is off fighting with the militia when Tories show up at her door looking for Patriots. She tries to prevent their entering, but they push their way in and search the house. They steal what they want, and run swords through mattresses,[9] without finding the wounded man.

During the Revolution, when Sarah Robinson Earvin is around 30, she is taking care of a neighbor, Samuel Alexander, a wounded Whig militiaman. Her husband Alexander is off fighting with the militia when Tories show up at her door looking for Patriots. She tries to prevent their entering, but they push their way in and search the house. They steal what they want, and run swords through mattresses,[9] without finding the wounded man.

Unfortunately, they think to look in the outhouse. Sarah rushes around and tries to block them again. Again they shove her aside and open the door. Samuel is inside. One raises his sword and swings it on the wounded man. Sarah throws herself between them, placing her right arm over the Patriot’s head, which takes the strike of the blade. She is badly wounded.

Sarah was maimed for the remaining four to five years of her life. She died from complications from the wound.

History does not record what happened to Samuel. We can assume it wasn’t good.

Cemetery

From wherever you are at this point:

- Drive back to Green Street, and turn left.

- Turn right at Independence Boulevard (NC 126) as the Overmountain Men did.

- Drive 0.4 miles to Sam Wall Drive on the right (unmarked as of 2020, it angles away from you uphill).

- Turn right, and then right again onto Branstom Drive.

- Follow it uphill to the end and park at the cemetery.

If unlocked, go through the right gate and walk up the front side of the closest long row of tombstones. Go to the 12th tombstone.

If the gates are locked, walk around to the 10th column on the right, not counting the big center one. Look at the two graves at the top of the hill straight behind the near column. We start with the one on the left.

Here lies Charles McDowell. Despite his role in putting together the army that defeated Ferguson at King’s Mountain, he was not there. Prior to these events he had won an important victory at Musgrove’s Mill (S.C.) but lost to Ferguson at Cane Creek. While the Overmountain Men were camped at that battlefield, another colonel was proposed for the overall command that McDowell had reason to claim. He gallantly volunteered to report on the campaign to the commander of the southern Continental Army in Hillsborough. (Learn more.)

Here lies Charles McDowell. Despite his role in putting together the army that defeated Ferguson at King’s Mountain, he was not there. Prior to these events he had won an important victory at Musgrove’s Mill (S.C.) but lost to Ferguson at Cane Creek. While the Overmountain Men were camped at that battlefield, another colonel was proposed for the overall command that McDowell had reason to claim. He gallantly volunteered to report on the campaign to the commander of the southern Continental Army in Hillsborough. (Learn more.)

To the right is Grace Greenlee Bowman McDowell, a heroine of the war and McDowell’s wife. Their wedding was her third, sort of. Her father had tried to marry her off to an elderly man, not uncommon in those days. She dutifully tried to go through with it, only to answer, when asked the standard “do you take” question… “No!”[10] She then married John Bowman, who became a Patriot militia captain. He was mortally wounded at the 1780 Battle of Ramsour’s Mill.[11] Grace rode with her toddler 40 miles on horseback across the South Mountains to today’s Lincolnton, and reached John in time to witness his death. (You can see his grave there.)

She came back to run their farm using enslaved laborers and help gather and ship supplies for Patriot forces. Several stories from an early source have been repeated about Grace in later ones. At least one cannot be true,[12] but it is possible she forced Tory raiders who had stolen her horses to return them—at musket point. In another, she was riding home alone when accosted by Tories who demanded information about Patriots in the area. “She told them there was nothing of interest to relate except that the McDowells were out with a large troop hunting for Tories, and were then approaching over the same road she had traveled.” They fled.[13]

After marrying McDowell in 1782, “while he was secretly manufacturing in a cave the gunpowder, she made the charcoal in small quantities in her fireplace, carrying it to him at night to prevent detection.”[14]

Joseph McDowell, Jr., also is buried somewhere in the cemetery. A 19th-Century source said he was beside Charles, which suggests the gap to the left. But the grave marker and thus the site is lost. The same is true for their parents Joseph and Margaret.

Notice the fourth tombstone to the left of Charles, for James Greenlee, whom we will meet at “his” ford below.

If at the grave, turn around. Walk downhill and to the left, to the row of three graves, and pass between the second and third on the far end (or from outside the fence, find that gap).

The grave directly below that gap in the next long row is Mary Bowman Tate. Perhaps you can read her birthdate, November 22, 1779. That made her 11 months old when her mother Grace carried her to her father’s side at Ramsour’s Mill.

Go back uphill to the two tombstones closest to the gate.

On the right is Sarah Erwin. If you haven’t already, read about her in the “Cherryfields” section above.

Her husband Alexander, to the left, was a captain of mounted riflemen from the earliest actions against Ferguson’s force, while still in South Carolina. Alexander was in the Battle of Cane Creek under McDowell, retreated across the mountains with those Patriots, and returned with the Overmountain Men. He continued with them to King’s Mountain and fought later in the Battle of Cowpens (S.C.). There’s no record of what he did in the Race to the Dan that battle triggered. Erwin fought in later campaigns against the Cherokees during the war, and stayed in the militia afterward, eventually rising to colonel. He also became a justice of the peace and served in the state House of Commons. After Sarah died from her wound, he married a widow he had met bringing her soldier husband’s belongings to her. In his elder years he was described by someone who knew him as “‘devoted to books and a thorough knowledge of the current literature, and withal, when young, a wit and a dandy.’”[15]

Greenlee Ford

Return to Independence Boulevard and:

- Turn right, and drive across the river.

- At the first major intersection, turn left on US 70 East (Carbon City Road).

- Drive 0.5 miles and turn left onto Greenlee Ford Road (at the sign for the soccer complex and greenway).

- Drive to the end, past the Catawba River Greenway sign.

- Park and take the trail off the end of the road, toward the river (not the greenway on the right as you enter the lot).

Read the marker for the ford, and then walk to the canoe launch to the right of the sign.

Read the marker for the ford, and then walk to the canoe launch to the right of the sign.

Notice that the river ripples more here than upstream to the left, unless it is flooding. That is because it is shallow enough here for horses and people to cross. The ford was named for James Greenlee, eventually related to the McDowells by marriage twice over, and one of the first people to speculate in land in the area. John Bowman was one of his partners. A Whig, Greenlee served in government during the war.

The 1,800 Overmountain Men and other militia passed in this direction on Sunday, October 1, probably taking a couple hours for the column to cross. Nearly as many return at night exactly two weeks later, dragging along their hundreds of exhausted and starving Loyalist prisoners.

Historical Tidbits

A few miles north of the Council Oak is the site of Joara, a Native American town where Spain established Fort San Juan in 1567, trying to enforce its claim on North America. The natives burned the fort a year later. The first English colony in mainland America was not founded until 1585 at Roanoke.[16]

A few miles north of the Council Oak is the site of Joara, a Native American town where Spain established Fort San Juan in 1567, trying to enforce its claim on North America. The natives burned the fort a year later. The first English colony in mainland America was not founded until 1585 at Roanoke.[16]- Overlooking Quaker Meadows is the home built by Col. McDowell as a wedding present for his son and namesake in 1812. A tour is highly recommended if open, or you can make an appointment through the Historic Burke Foundation. The barn behind it is original. The kitchen is a reproduction built on the original foundation. Among the McDowell enterprises was a brick-making business. This perhaps explains the unusually thick “Flemish bond” brickwork visible in the house’s exterior—maybe it was a marketing tactic![17] The lane on the far side of the house from the parking lot is the one mentioned as coming downhill to McDowell Station. An informational panel about the Overmountain Men is in front of the house. From Bost Road, turn right on Green Street. Drive one block to St. Mary’s Church Road. After a short distance, turn left into the driveway of the Capt. Charles McDowell, Jr., House.

More Information

- ‘1914 Council Oak at Quaker Meadows-Point of Assembly for OVM’, The News-Herald (Morganton, North Carolina, 1 October 1914), p. 3

- Coley, Scott, McDowell House, In-person interview with tour, 2020 (a)

- Coley, Scott, Quaker Meadows and the McDowells, Phone interview, 2020 (b)

- Collins, III, Clarence, ‘Sarah Anne Robinson Erwin (P-280660)’ (North Carolina Sons of the American Revolution) <http://www.ncssar.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Sarah-Robinson-Erwin.docx>

- Erwin, Jr., Sam, ‘Erwin, Alexander’, NCpedia, 1986 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/erwin-alexander> [accessed 25 February 2020]

- Ervin, Eunice, Under the Forest Floor (The Historic Burke Foundation, 1997)

- Johnson, Uzal, Uzal Johnson, Loyalist Surgeon: A Revolutionary War Diary, ed. by Bobby Gilmer Moss (Blacksburg, S.C: Scotia Hibernia Press, 2000)

- Jones, Randell, Before They Were Heroes at King’s Mountain, North Carolina/Tennessee Edition (Winston-Salem, NC: Daniel Boone Footsteps, 2011)

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Charles McDowell’, The Patriot Leaders in North Carolina, 2013 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/patriot_leaders_nc_charles_mcdowell.html> [accessed 24 February 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Quaker Meadows’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2009 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_quaker_meadows.html> [accessed 24 February 2020]

- ‘Marker: N-3’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=N-3> [accessed 22 February 2020]

- ‘Quaker Meadows’, Battle of Kings Mtn <https://bkmnp.com/ovta/quaker-meadows/> [accessed 22 February 2020]

- ‘Quaker Meadows’, Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail (U.S. National Park Service) <https://www.nps.gov/ovvi/learn/historyculture/quaker-meadows.htm> [accessed 22 February 2020]

- ‘The Berry Site’, Exploring Joara Foundation <https://exploringjoara.org/the-berry-site/> [accessed 4 June 2020]

- ‘The Captain Charles McDowell, Jr. House’, Historic Burke Foundation <https://www.historicburke.org> [accessed 22 February 2020]

[1] Coley 2020b.

[2] Jones 2011.

[3] Quoted in multiple sources.

[4] Coley 2020a.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Coley 2020b.

[7] Ervin 1997.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Barefoot 1998.

[12] Supposedly soldiers under an infamous British cavalry commander, Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, stole some of her horses, and Sarah went to the camp to demand them back. But Tarleton never came close to Quaker Meadows, even during the British invasion of 1781. He shows up as a villain in a number of stories at places across N.C. where he could not have been!

[13] Ervin.

[14] Lewis 2013.

[15] Ervin.

[16] The Berry Site.

[17] Coley 2020a.

[a] Johnson 2000.

← Turkey Cove | Overmountain Tour | Cane Creek →