Patriots Ambush and Overmountain Men Camp

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.5860, -81.8357.

Type: Sight

Tour: Overmountain

County: McDowell

![]() Full

Full

The coordinates point to a parking area primarily for game hunters but also containing a historical marker about the site. Everything is visible from a vehicle in the lot or the entrance by the highway.

Please see our Hurricane Helene page about likely impacts to this location from the 2024 floods.

Context

A British corps under Maj. Patrick Ferguson made up mostly of Loyalists is attempting to eliminate Patriot resistance in the western part of the state prior to invasion by the main British army.

A British corps under Maj. Patrick Ferguson made up mostly of Loyalists is attempting to eliminate Patriot resistance in the western part of the state prior to invasion by the main British army.

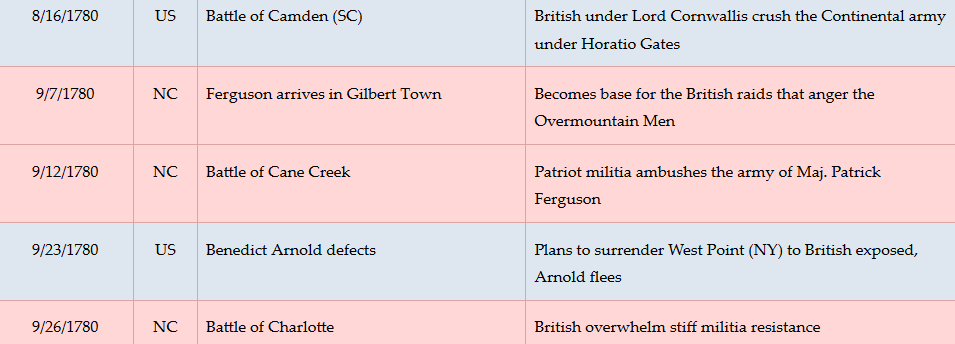

Situations

British/Tory

On learning Patriot part-time “militia” troops under Col. Charles McDowell were camped on Cane Creek[1], Ferguson and part of his “American Volunteers” marched up it from Gilbert Town (near today’s Rutherfordton) to attack him. Loyalist (Tory) Lt. Alexander Chesney wrote they “‘crossed the winding creek 23 times (and) found the rebel army strongly posted towards the head of it near the mountains.’”[2]

Patriot

McDowell was moving up the Broad River toward today’s Tennessee (then still part of N.C.) when he learned of Ferguson’s plan. He prepared an ambush above one of the many fords of the creek. It is unclear how the two forces passed each other, but Tory Lt. Anthony Allaire states the British had gone a different way than the Patriots expected.

Overmountain Men

Around this time, Ferguson threatened to cross the mountains to attack rebels there (see “Gilbert Town”). This backfired, causing the Patriots we now call the Overmountain Men to join with McDowell’s forces and others in a preemptive strike. Thus the war returned to this spot.

Date

Tuesday, September 12, 1780.

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

The Battle

Walk or drive to the gravel driveway entrance for the parking area at US 64, and face the highway.

The exact location and series of events for this battle are not clear, even after a 2017 investigation by an archaeologist/historian for the National Park Service.[3] This page describes a likely scenario based on the evidence found and the account of a Loyalist officer at the battle (see “Historical Tidbits” below). Believe with caution!

The exact location and series of events for this battle are not clear, even after a 2017 investigation by an archaeologist/historian for the National Park Service.[3] This page describes a likely scenario based on the evidence found and the account of a Loyalist officer at the battle (see “Historical Tidbits” below). Believe with caution!

Ferguson’s detachment of 100 regular British “Redcoats” and 40 Loyalist militia is marching down the valley, right to left, after passing through the gap US 64 uses now. (There was no road then.) They had hoped to surprise McDowell at his camp on the far side of the gap by modern Brindletown, but found it abandoned and are returning this way.

Look to your left at the hill to the right of the highway.

You are looking at Bedford Hill. McDowell’s troops, about 200 men, are in position facing this direction. But you, and Ferguson’s force, cannot see them. The hill is forested, and the Patriots are hidden behind the trees.

The militia at the front of Ferguson’s column passes you to continue down the valley between the hill and Cane Creek behind you, led by British Capt. James Dunlap.

Suddenly there is a blast of gunfire, and you see a huge cloud of smoke shoot out from the hillside. Some of the British fall, including Capt. Dunlap, receiving flesh wounds from balls in his thigh and groin.[a] Known for riding ahead of his troops, Dunlap was “‘badly wounded by some skulking shots on the flank’” according to Ferguson. But the rest of the men overcome their surprise, form into a line, and start rushing up the hill.

The Patriots defend themselves briefly. However, despite outnumbering the enemy, they then take off over and around the crest.

This story ends on the far side of the hill, as described after the next section.

The Overmountain Camp

Three weeks after the battle, on Sunday, October 1, an army of 1,400 Patriots arrives. They are coming from Quaker Meadows (in modern Morganton) down the same route Ferguson used. These farmers and craftsman, including formal militia units and other volunteers, expect to attack Ferguson at Gilbert Town. They flow out into the area between Magazine Creek (running side to side on the farmland across the modern highway) to the headwaters of Cane Creek, which runs along the left side of the field next to the parking area. At the time the whole area is forested. Having no tents, they make camp under the trees for what shelter those offer from a rain that started that afternoon.

Go down to the field.

The next day they wake up to more rain. These are not trained soldiers, and feel stuck and frustrated. Arguments break out all around you, and a few fistfights.

The next day they wake up to more rain. These are not trained soldiers, and feel stuck and frustrated. Arguments break out all around you, and a few fistfights.

Somewhere in the camp, all of the colonels meet to discuss the day’s problems. They decide there is a need for an overall commander. Someone suggests a courier be sent to Hillsborough to request a regular army officer from the commander of the Continental army stationed there, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates.

Without disagreeing, Isaac Shelby notes that they need someone in command now, given that they are within striking distance of Gilbert Town. He suggests William Campbell. Shelby says Campbell is a good officer—and perhaps more importantly, the only Virginian among the colonels.

The truth, Shelby wrote in 1823, was he made the suggestion “‘to silence the expectations of Colonel McDowell to command us.’” These are reasonable given that McDowell has been a colonel the longest and the fact they are in his multi-county “district” of the state. “‘He was a brave and patriotic man, but we considered him too far advanced in life, and too inactive for the command of such an enterprise as we were engaged in,’” Shelby wrote.[4] (McDowell was only 37, if that; some historians suggest McDowell’s defeat here where they now are camped has something to do with the decision.)

Campbell takes Shelby aside. He asks Shelby to withdraw the suggestion. But Shelby refuses. He points out he can’t take command himself because he is the youngest colonel and has served under McDowell, who would be offended to have Shelby promoted over him. Shelby convinces Campbell to accept, and they go back to the others.

McDowell gallantly agrees to step aside. Perhaps to avoid embarrassment, he offers to turn over command of his regiment to his brother, Maj. Joseph McDowell, and inform Gates of the campaign. Though a few sources say he rides off immediately, a letter dated three days later hints otherwise. Written by Col. Benjamin Cleveland to Gates and signed by the other colonels, it requests a regular army commander. “All our Troops being Militia, and but little acquainted with discipline, we could wish him to be a Gentleman of address, and able to keep up a proper discipline, without disgusting the Soldiery,” Cleveland writes. He adds, “Colo. McDowell will wait upon you with this, who can inform you of the present situation of the Enemy…” Thus it seems McDowell suffered through staying with the force until it moved into Gilbert Town on the 4th.[b]

Tuesday morning arrives. The weather has cleared. Cleveland calls the men together in a large circle around the officers. He confirms the time has come to confront Ferguson. He tells them this is their final opportunity to back out. Joseph McDowell applies some pressure, however, by asking them what story they will tell those back home if they do.

Shelby then supposedly says: “You have all been informed of the offer. You who desire to decline (to fight), well, when the word is given, march three steps to the rear, and stand, prior to which a few more minutes will be granted you for consideration.”

He waits the few minutes, and then gives the order.

No one moves.

Some of the men applaud. Shelby clearly is moved. He gathers himself and says: “I am heartily glad to see you to a man resolve to meet and fight your country’s foes. When we encounter the enemy, don’t wait for the word of command. Let each one of you be your own officer, and do the very best you can, taking every care you can of yourselves, and availing yourselves of every advantage that chance may throw your way.”

They are dismissed and told to prepare to march in a few hours. When ready, they head down Cane Creek the same way Ferguson did after the battle.

McDowell Camp

Return to your car and turn left onto US 64. Veer onto the second right, Bill Deck Road. You are now following the later Morganton-Rutherfordton Road used by stagecoaches. As it starts to curve right, pull off to the left.

McDowell’s Patriots may have been camped here awaiting Ferguson’s approach from the south, not realizing he had already gone past directly up Cane Creek. Or perhaps the Tories went behind the hill on the way north.

McDowell’s Patriots may have been camped here awaiting Ferguson’s approach from the south, not realizing he had already gone past directly up Cane Creek. Or perhaps the Tories went behind the hill on the way north.

During the battle, the British and Tories finish climbing the hill here and clear the camp. Altogether they capture 17 Patriots, 12 horses, and a stash of 20 pounds of gunpowder. Most of them follow the Patriots a short distance north (right) along the route of today’s NC 226, just ahead of you, toward today’s Marion.

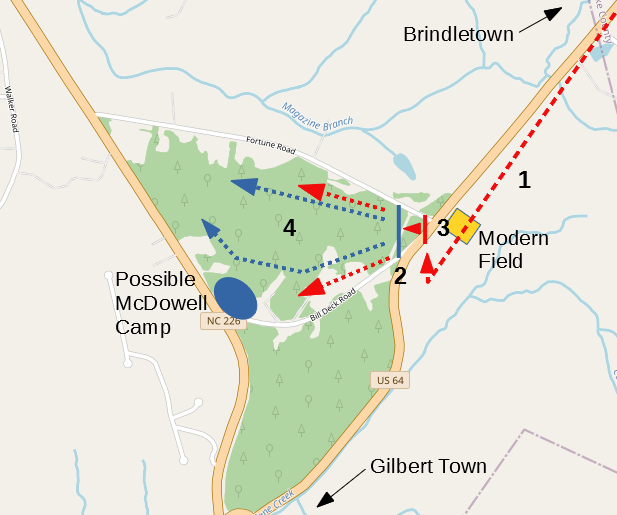

Battle Map

The Battle of Cane Creek: One likely scenario; all locations are approximate. 1) Ferguson’s American Volunteers detachment marches toward Cane Creek. 2) Patriots ambush Loyalists. 3) Loyalists form line and attack uphill. 4) After brief defense, Patriots break and Loyalists chase for a short distance.

Casualties

Historical Tidbits

- An archeological survey of possible battle sites along the creek was published in 2017.[5] Among them, the highest concentrations of lead bullets were at three locations: the south end of the field you parked in, across the road from the hill; on that side of the hill, along with a slug of lead for making more; and at the possible McDowell campsite at Bill Deck Road and NC 226. This physical evidence is the primary reason this page locates the battle east of Bedford Hill instead of further south. (The field location is where you would expect to find balls shot at the Tories in the volley from the hill.) Another reason is Allaire’s statement in his diary that Ferguson initially passed the Patriots on the way to Brindletown. That could not have happened in the narrow valley to the south. Finally, a British surgeon wrote in his diary that the Patriots “drew up on an eminence.”[c]

- If you are taking the Overmountain Tour, you will follow the Patriots for part of their route. For unclear reasons, they camp twice over the distance Ferguson’s corps traversed in a single day. No doubt the ground was marshy or muddy after two days of rain, and the Patriots had come a much longer distance. You will pass the first campsite on the way to the next location (see “Bickerstaff’s Old Fields”).

More Information

- Allaire, Anthony, Diary of Lieut. Anthony Allaire (New York: New York Times, 1968) <http://archive.org/details/diaryoflieutanth0000alla>

- Barefoot, Daniel, Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1998)

- Chávez, Karen, ‘Land Trust Protects Water, Battlefield’, Citizen Times, 2016 <https://www.citizen-times.com/story/news/local/2016/12/08/land-trust-protects-water-historic-battlefield/95048316/> [accessed 30 March 2020]

- Cleveland, Benjamin, ‘Letter from Benjamin Cleveland et al. to Horatio Gates’, 10/4/1780, in Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Vol. XIV <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0562> [accessed 22 April 2021]

- Conley, Mike, ‘Grant Will Help Pinpoint Cane Creek Battle Site’, Com <https://www.mcdowellnews.com/news/grant-will-help-pinpoint-cane-creek-battle-site/article_3dede732-fea5-11e2-bd64-001a4bcf6878.html> [accessed 3 February 2020]

- Draper, Lyman Copeland, King’s Mountain and Its Heroes: History of the Battle of King’s Mountain, October 7th, 1780, and the Events Which Led to It (Cincinnati: Peter G. Thomson, Publisher, 1881) <http://archive.org/details/cu31924032752846> [accessed 31 March 2020]

- ‘Episode 23 – South Mountain Pass and Trouble in the Ranks’, Mitchell County Historical Society, 2019 <https://mitchellnchistory.org/2019/10/02/episode-23-south-mountain-pass-and-trouble-in-the-ranks/> [accessed 30 March 2020]

- Johnson, Uzal, Uzal Johnson, Loyalist Surgeon: A Revolutionary War Diary, ed. by Bobby Gilmer Moss (Blacksburg, S.C: Scotia Hibernia Press, 2000)

- Jones, Randell, ‘The Story – Bedford Hill’, Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail <http://bythewaywebf.webfactional.com/omvt/items/show/48?tour=2&index=8> [accessed 30 March 2020]

- Kota, Andrew, ‘Status of Cane Creek Battlefield’, e-mail, 30 March 2020

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Cane Creek’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2013 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_cane_creek.html> [accessed 3 February 2020]

- ‘Marker: N-41’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=N-41> [accessed 3 February 2020]

- Robinson, Kenneth, Skirmish at the Head of Cane Creek: A Revolutionary War Prelude to the Battle of King’s Mountain (Report Prepared for the Foothills Conservancy of North Carolina, Morganton, N.C. with support from the American Battlefield Protection Program, National Park Service (Grant # GA228713008) and the Overmountain Victory Trail Association, 12 February 2017)

- Sherman, Wm. Thomas, Calendar and Record of the Revolutionary War in the South: 1780-1781, Tenth Edition (Seattle, WA: Gun Jones Publishing, 2007) <https://www.americanrevolution.org/calendar_south_10_ed_update_2017.pdf>

- ‘The Skirmish at Cane Creek (First)’, American Revolutionary War <https://www.myrevolutionarywar.com/battles/800912-cane-creek/> [accessed 30 March 2020]