A Leading Voice for the Regulators

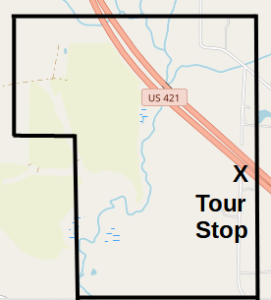

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.8573, -79.6163.

Type: Stop

Tour: Regulators

County: Randolph

The coordinates are at the end of a half-mile gravel road, State Road 2518 (Curtis Lane on maps, though there is no road sign). Park where the gravel ends, before the route takes a sharp left into a dirt farm lane on private property. You will hear traffic on Highway 421 in front of you. The continuation of this road on the north side, cut off by the highway, is named Herman Husband Road.

You may remain in your vehicle.

Description

Herman Husband

Look left across the farm field. Everything you see to the far horizon was part of Herman Husband’s “Cabbin (sic) or No. 1” tract, where his home was built. (Your view may be blocked by crops!) Two local historians were unable to find physical traces of his home or buildings, however, on any of his former lands. The home and one of his mills may have been destroyed by the highway’s construction.[1]

He was a wanderer in body and spirit, Herman Husband of Maryland, one of a dozen children of former indentured servants[2] turned wealthy slaveholders. Despite having no formal education, Husband was a bookworm who owned 800 pamphlets when he died and had corresponded with Benjamin Franklin.[3] Raised Anglican, he was Presbyterian for a while, and then became a Quaker. From 1750 to 1762, Husband shifted from Maryland to Barbados to North Carolina and back to Maryland again, before settling down on 640 acres along Sandy Creek, a small part of the 10,000 he eventually owned in the colony. The creek runs right to left at the base of the plateau in front of you, marked by a line of trees.

Husband first raised concerns about colonial government practices as early as 1754, and formed a group to fight local corruption in 1766. Although Husband never formally joined the Regulators, protesters against corruption and unfair taxation, he wrote and spoke on their behalf.

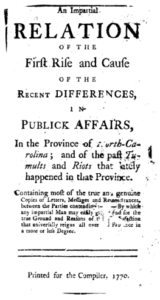

For example, in 1770, he published anonymously a 104-page booklet called, “An Impartial Relation of the Rise and Cause of the Recent Differences in Public Affairs in the Province of North Carolina; and of the Past Tumults and Riots that Lately Happened in that Province.”[4] Though hardly impartial, Husband retells the history of the Regulator movement to that point, quoting many of the original petitions and letters at length. Colony leaders, mostly eastern landowners, tried to claim backward westerners were the problem. In it he points out that eastern counties such as Halifax had raised similar concerns.

For example, in 1770, he published anonymously a 104-page booklet called, “An Impartial Relation of the Rise and Cause of the Recent Differences in Public Affairs in the Province of North Carolina; and of the Past Tumults and Riots that Lately Happened in that Province.”[4] Though hardly impartial, Husband retells the history of the Regulator movement to that point, quoting many of the original petitions and letters at length. Colony leaders, mostly eastern landowners, tried to claim backward westerners were the problem. In it he points out that eastern counties such as Halifax had raised similar concerns.

In his conclusion, he explains why correcting the record, as he saw it, was important. He writes, “The first slavery that men are generally brought under, is the slavery of the mind; for while the mind acts freely, and is kept clear of the chains of ignorance and prejudice, it would be very difficult to enslave them—It therefore requires the aid of false Teachers to reduce mankind before a state can deprive them of their civil liberties and privileges.” He closes with an attack on a range of such people for helping suppress liberty.

In 1768 Husband was jailed in Hillsborough as a suspected leader of the Regulators. A large group of them marched to town and forced his release. The next year, he was elected to the colonial legislature, and it seems right that he was named to a committee overseeing public finances. He read to the assembly a petition calling for an accounting of public funds from Orange County, the arrest of county officers extorting fees, and impartial juries. The 174 petitioners said juries were assigned by, and sometimes included, the people they accused of extortion![a]

Instead of taking action on the petition, in December of 1770 the House of Commons kicked him out. On the 10th, meeting in New Bern, it had authorized the governor to take action against the Regulators. Four days later, a letter was published in the local newspaper from a Regulator leader attacking the delegate that introduced the bill. Somehow the House decided Husband submitted the letter, lied to the house about it, and was a “principal mover” of the Hillsborough riots (despite the fact he was in jail during the first one!). They also complained that he had suggested if the House arrested him, the Regulators would free him.[b] He was jailed on a libel charge for the letter, but was acquitted.

With Royal Gov. William Tryon’s army approaching this region to quell the Regulators in 1771, Husband tried to arrange a truce, but left the field before the Battle of Alamance that destroyed the movement. (Though booted out of the Cane Creek Meeting over a disagreement about readmitting a rape victim,[5] he retained the pacifism of most Quakers. The Regulators do not appear to have blamed him for leaving.) Knowing the governor would come after him, he fled through Bethabara using the alias “Toscape Death.” He escaped to Pennsylvania despite a substantial reward offered by Tryon: £100, worth about $18,000 today, and 1,000 acres of land.[6]

During and after the Revolution, he served in county and state government there and wrote extensively on political and religious matters. After participating politically in the first armed resistance to the new United States, the Whiskey Rebellion, he was jailed yet again. Husband was acquitted and pardoned by Pres. George Washington at the urging of North Carolina politicians. However, he died in Philadelphia soon after his release, from pneumonia he contracted in jail.

Husband appears as a character in the Outlander books and TV series.

Tryon Takes Advantage

A road to the right of the farm beyond the trees was apparently built by Husband as a shortcut to Hillsborough, the site of the Orange County Courthouse.[7] (This area was part of Orange at the time.) Along with selling land and raising wheat, Husband built several grain mills in the area. It’s unclear where his were, among half-a-dozen in the vicinity. One of his mills hosted meetings of the Regulators. Unusually for the time, he took a large loan to pay for part of his property, from a man named Gregg.

After the battle, Tryon’s army continued west to rescue another militia force, under Gen. Hugh Waddell, that Regulators had trapped in Salisbury. The army camped here on Husband’s plantation on Tuesday, May 21, 1771. Tryon describes it as 600 acres of “Excellent Land.” He says, “A large parcel of Treasonable papers (were) found in his Home, and some of his Stock, and Cattle, on or near the plantation.”[8] He mentions they have no account of Husband after the battle.

The army was made up of company-sized volunteers from the existing county regiments of part-time soldiers called “militia.” Per his orders earlier in the campaign, the companies likely camp in two lines in the same order they used in the battle, 200 yards between them, and five paces between each company.

One of Tryon’s officers reported in a letter that Husband “had growing on his Plantation about 50 Acres of as fine Wheat as perhaps ever grew, with (a) Clover Meadow equal to any in the Northern Colonies…” The fields were likely downslope from you, nearer the creek. However, 400 horses turned out to graze by the army “in a few days left it without a Spear of Corn, Grass, or Herbage growing, and without a House or Fence standing!” Presumably it was the army, not the horses, which destroyed the house somewhere near you, and the fences probably became firewood.

Regulators come in to accept a pardon offered by the governor after the battle. They must agree to leave their guns here and pledge loyalty to the King, among other conditions. Also here during the army’s stay, according to Tryon’s collected orders, letters, and journal,[9] on:

- Wednesday the 22nd:

- A court martial is held for a few prisoners, with Col. Samuel Ashe presiding.

- Tryon offers a reward of $2 for, “Lost in the Field on the Day of Battle a blue Husar [sic] Cloak…” (“Hussar,” originally referring to cavalry in Hungary, came to mean any fancy-dressed cavalry officer.)

- He sends out the Wake and Cumberland companies plus a “Light Horse” cavalry troop of volunteers to rescue wagons sent to two mills to the east to get flour. Quakers had informed him Regulators stopped a detachment sent to Lindley’s Mill, near today’s Eli Whitney.

- Thursday, 23:

- Heavy rain and resultant flooding hold the army in place.

- The flour wagons arrive, with three extra taken from Dixon’s Mill by modern Snow Camp, N.C., because of Simon Dixon’s support for the Regulators—he hosted at least one meeting at his mill. This makes for 70 barrels of flour. Tryon sends requisitions for different numbers of beef cattle and more flour from each town or region in the central part of the colony. They total 415 cows, and 293 barrels on top of those already delivered.

- He gives rewards to all of the noncommissioned officers (like sergeants) and soldiers for the arms and horse tack they turned in after the battle.

- In response to a letter from the commander of the Surry County Regiment, Tryon agrees he should move toward the army, but orders him to halt five miles short and send a messenger. (Perhaps this was a precaution against army scouts mistaking the regiment for Regulators.)

Remains of Cox’s Mill (no public access; AmRevNC photograph) Friday, 24: Col. Edmund Fanning is sent with the Orange County Company to Harmon Cox’s Mill, below today’s Ramseur, to claim food. (Cox, too, hosted the Regulators.) More heavy rains soak the army all day.

- Saturday, 25: Again rains prevent a march. The colonels are ordered to try Col. William Johnston of the Bute County Regiment for failing to raise the number of men Tryon required from it prior to the campaign. He is found guilty and removed from command.

- Sunday, 26:

- Tryon threatens courts-martial if men keep firing off weapons in camp, against orders.

- A “ranger” unit is sent to join the Orange detachment for an unexplained reason, but is blocked by flooding at Polecat Creek nine miles west of here.

- Noting that 1,300 men from around the Deep River have come in for the parole, he writes Waddell that there is no “advantage” to Waddell staying near Salisbury. Tryon orders him to join the army “at the upper Ford of the Deep River where the Trading Path crosses,” near Randleman.

- Monday, 27:

- Deserters are court-martialed.

- Tryon states the men have no tents, “or any thing to shelter them but Boughs and the Bark of Trees” from seven days of rain. Almost a hundred have fevers. (The lack of tents is unexplained. His orders before the battle explicitly stated tents were to be left standing. Possible explanations include their being left behind to free up wagons for flour, or that the constant rains have rotted them.)

- Tuesday, 28: The army finally marches west at 2 p.m., presumably using the road pictured above.

A local historian wrote that, “It appears that all of Husband’s property was either confiscated or destroyed by Governor Tryon, and it isn’t clear whether Gregg’s mortgage was respected.”[10]

To learn about the army’s other stops, see “Tryon’s March.”

Another Army Arrives

Move exactly 10 years ahead in time to visit another army:

- Return to Ramseur-Julian Road and turn left.

- Drive to the first cross-street, Old Liberty Road, and turn left.

- Drive a short distance to the one-lane bridge over Sandy Creek.

- Park on the right, in the circular driveway of the former miller’s home, on the end of the drive nearest the bridge.

Both to respect the property owner’s rights and for your safety, please remain in your vehicle within the public right-of-way on the road shoulder.

Samuel Walker’s Mill was right next to you between here and the bridge.[11] A dam and mill pond was to the left of the road. In March of 1781, the British army of Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis had won, but been badly injured at, the Battle of Guilford Court House in today’s Greensboro. After spending time on or near the battlefield, Cornwallis moved to Bell’s Mill west of here. At some point he decided to go to Cross Creek (modern Fayetteville) to recover within the safety of a Loyalist region. On Thursday, March 22, 1781, the army stopped here.[12]

More than 2,000 people would have camped over two square miles extending onto some of Husband’s land. They huddled around campfires, Cornwallis having ordered the army’s tent wagons destroyed before the battle to move faster. Besides the soldiers, many of them wounded, there were camp followers, and possibly some Loyalist refugees and people escaping slavery. They left the next day in the direction you are facing for Dixon’s Mill, mentioned above.

Walker’s Mill may have been replaced in the 1820s, and that building existed into the 1950s. The dam, still visible across the road when leaves are down, was purposely breached in that decade to prevent an uncontrolled break when a hurricane came through. To your right is the remodeled miller’s house, dating before the Civil War.[13]

More Information

- Bassett, John S., ‘The Regulators of North Carolina (1765-1771)’, Documenting the American South, 1894 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/bassett95/bassett95.html> [accessed 15 February 2020]

- Fasano, Chris, ‘Regulators of North Carolina’, American Legal History, 2009 <http://moglen.law.columbia.edu/twiki/bin/view/AmLegalHist/ChrisProject> [accessed 14 December 2020]

- Fries, Adelaide L., Records of the Moravians in North Carolina. Volume I: 1752-1771 (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton Print. Co., 1922), <http://archive.org/details/recordsofthemora01frie> [accessed 14 October 2020]

- Jones, Mark, ‘Husband (or Husbands), Herman (or Hermon, Harman)’, NCpedia, 1988 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/husband-or-husbands> [accessed 22 April 2020]

- ‘Marker: K-62’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=K-62> [accessed 22 April 2020]

- ‘Minutes of the Lower House of the North Carolina General Assembly, Volume 08, Pages 105-141’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1769 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr08-0068> [accessed 7 January 2022]

- ‘Minutes of the Lower House of the North Carolina General Assembly, Volume 08, Pages 302-346’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1770 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr08-0168> [accessed 7 January 2022]

- ‘Minutes of the North Carolina Governor’s Council, Volume 08, Pages 268-270’, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1770 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr08-0160> [accessed 7 January 2022]

- Neill, James, Alamance Battleground, Interview with tour, 10/21/2020

- ‘Petition from Inhabitants of Orange County Concerning Taxes and Fees for Public Officials, Volume 08, Pages 231-234’, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1770 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr08-0139> [accessed 7 January 2022]

- Powell, William, ed., The Correspondence of William Tryon and Other Selected Papers (Raleigh, N.C.: Division of Archives and History, Dept. of Cultural Resources, 1980) <http://archive.org/details/correspondenceof1981tryo>

- Powell, William, James Huhta, and Thomas Farnham, eds., The Regulators in North Carolina: A Documentary History, 1759-1776 (Raleigh, N.C.: State Dept. of Archives and History, 1971)

- Quinn, James, ‘Herman Husband, a Time-Line’, New River Notes <https://www.newrivernotes.com/carroll_history_1779-1783_flower_swift_husband.htm> [accessed 22 April 2020]

- ‘“Shew Yourselves to Be Freemen”: Herman Husband and the North Carolina Regulators, 1769’, History Matters <http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6233/> [accessed 22 April 2020]

- Whatley, L. McKay, ‘Husband’s Homesite, E-Mail’, 11/16/2020

- Whatley, L. McKay, ‘Nixon’s Pond/ Husbands’ Mill’, Notes on the History of Randolph County, NC, 2009 <https://randolphhistory.wordpress.com/2009/05/07/nixon%e2%80%99s-pond-husbands%e2%80%99-mill/> [accessed 2 July 2020]

[1] Dixon 2020, Whatley 2020. Tract location confirmed by AmRevNC using an overlay of the original deed map (from Powell et al. 1971) on a modern road map, aligning the lower portion and upper forks of Sandy Creek. The hand-drawn map does not align perfectly, so the tract map boundary is approximate.

[2] People who committed to seven years (typically) of virtual slavery in exchange for passage to America plus room and board, and sometimes training in a craft.

[3] Bassett 1894.

[4] Digital copy at Fasano 2009.

[5] Neill 2020.

[6] Fries 1922; modern value from: Nye, Eric, ‘Currency Converter, Pounds Sterling to Dollars, 1264 to Present’ <https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm>.

[7] Dixon.

[8] Powell 1980.

[9] All information and quotes in this list are from Tryon, in Powell.

[10] Whatley 2009.

[11] Dixon.

[12] Dixon, based on two primary sources: the journal of a Hessian regiment (German mercenaries), and another from a Scottish officer. Contrary to local tradition, records found by Dixon prove this to be Walker’s Mill, mentioned in those sources, and not one of Husband’s.

[13] Whatley 2009.

[a] “Petition from Inhabitants of Orange County…”

[b] “Minutes of the Lower House… Volume 08, Pages 302-346.”

← Dixon’s Mill | Regulators Tour | Faith Rock →