Immortals Can’t Protect a Cherokee Town

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.1848, -83.3739.

Type: Sight

Tour: Cherokee

County: Macon

![]() Full

Full

Though it looks like a parking lot, Nikwasi Lane at the coordinates is a public street. Park next to the grass-covered mound. If you wish, walk to the display at the south end of the mound (to the right).

Please see our Hurricane Helene page about likely impacts to this location from the 2024 floods.

Context

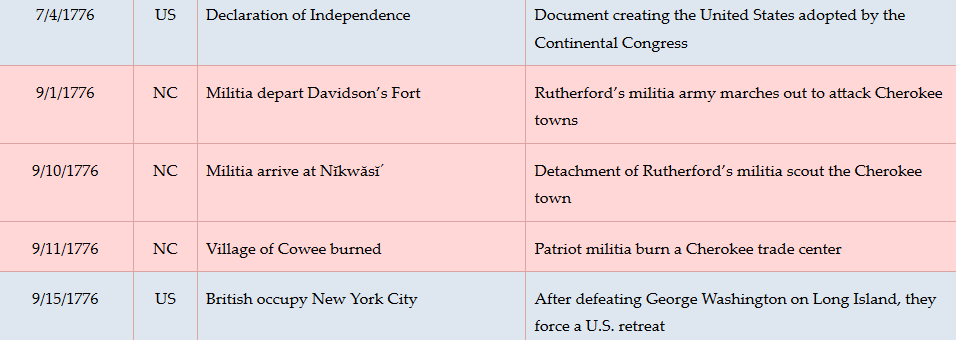

In retaliation for a series of attacks on European-Americans by Cherokees resisting incursions on their lands in 1776, commanders from the Carolinas and Virginia have launched coordinated campaigns to destroy their villages.

In retaliation for a series of attacks on European-Americans by Cherokees resisting incursions on their lands in 1776, commanders from the Carolinas and Virginia have launched coordinated campaigns to destroy their villages.

Situation

Cherokee

Warned by people retreating across Cowee/Watauga Gap of the approaching North Carolina army, those unable to fight have crossed the western mountains to refuge. Most of the men await the armies along the main route deeper into the mountains at Wayah Gap (see Battle of the Black Hole).

Militia

After crossing the Cowee/Watauga Gap, the army of part-time “militia” soldiers under Brig. Gen. Griffith Rutherford has occupied the village of Wata´gi to the north of modern Franklin.

Dates

Tuesday, September 10–Monday, September 30, 1776.

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

The Mound of the Immortals

Franklin has replaced the village of Nĭkwăsĭ´ (pronounced “nee-kwah-SEE”[1]). In the summer of 1776 log houses, farm fields, wooden sweat lodges, and one or more granaries cover 100 acres[2] surrounding this mound. As made clear by the drawing on the marker, what is left of the mound is less than a third of the original footprint and much shorter. The mound dates back to around 1,000 C.E., built by Mississippian Culture Native Americans.

Franklin has replaced the village of Nĭkwăsĭ´ (pronounced “nee-kwah-SEE”[1]). In the summer of 1776 log houses, farm fields, wooden sweat lodges, and one or more granaries cover 100 acres[2] surrounding this mound. As made clear by the drawing on the marker, what is left of the mound is less than a third of the original footprint and much shorter. The mound dates back to around 1,000 C.E., built by Mississippian Culture Native Americans.

Atop it is a council house or “townhouse.” After the Cherokee moved to the area, Nĭkwăsĭ´ became a center of worship to their Creator God. A “‘fire that had always been fire’” burned on an altar in the townhouse, with the belief the Cherokees would not perish as long as the flame lasted. When other towns adopted a ritual of rekindling their sacred fires each year, the flame here was the source. A tribal storyteller said it was moved before a 1761 British invasion (see “Historical Tidbits” below), and placed in a smoke hole on the south side of Hickory Nut Mountain.[a]

There is an ancient story told of this mound, recounted in a 1900 compilation of Cherokee stories for the Smithsonian Institute.[3] Before the arrival of Europeans, Creeks or another nation attacked towns to the southeast. The Cherokee warriors of Nĭkwăsĭ´ went to meet them downriver but were beaten back. A strange chief they assumed to be from the Upper Towns across the mountains told them to withdraw so his warriors could support them. The story continues:

“They fell back along the trail, and as they came near the townhouse they saw a great company of warriors coming out from the side of the mound as through an open doorway. Then they knew that their friends were the Nûñnĕ´hĭ, the Immortals, although no one had heard before that they lived under Nĭkwăsĭ´ mound.

“The Nûñnĕ´hĭ poured out by hundreds, armed and painted for the fight, and the most curious thing about it all was that they became invisible as soon as they were fairly outside of the settlement, so that although the enemy saw the glancing arrow or the rushing tomahawk, and felt the stroke, he could not see who sent it. Before such invisible foes the invaders soon had to retreat… As they retreated they tried to shield themselves behind rocks and trees, but the Nûñnĕ´hĭ arrows went around the rocks and killed them from the other side, and they could find no hiding place.”

The Immortals then returned to the mound, where they are believed still to live. (See the “Historical Tidbits” for other pre-war stories about the mound.) However, the Cherokee are wise enough not to rely on them. On word of the approach of the “outsider” army, they have abandoned the village.

Approach of the Militia

Thus there is no one to “greet” an advance unit of 600 militia who appear from the north on Tuesday, September 10, 1776. They inspect the houses, surely climbing the mound to check inside the townhouse. Most go south to a nearby village, some possibly continuing further, trying to meet up with South Carolina forces headed this way. An unknown number apparently go back the way they came to report their findings, which includes a lot of harvested corn.

Four days later, the entire army arrives from Cowee to the north and camps in the deserted town, for a total of around 2,400 men with more than a thousand pack horses. This is the end of the road for Capt. Erven, Sr., of the Mecklenburg County Regiment (first name unknown). He dies here, according to Lt. William Lenoir. Lenoir doesn’t say whether this was from natural causes, the greatest killer of soldiers in the 18th Century, or from a wound Erven might have received in a skirmish above Cowee.

The next day officers gather somewhere—we can guess it is in the townhouse—for a “council of war” to discuss strategy. They decide to leave a number of men behind while the rest of the army moves west to attack more towns. Monday the 16th, the main force heads south for unknown reasons (to the right when facing the bridge) and eventually west.[b]

Return and Fire

The army returns around 4 p.m. on Sunday the 29th by way of Wayah Gap, having destroyed a dozen towns and crops in a loop as far as modern Murphy, near which they finally met up with the South Carolinians. The armies followed “a standard tactic—burn every house, cut down or trample the crops, seize or kill livestock, kill any Cherokees that fought back, and move on to the next towns… In some cases, prisoners would be taken and sold as slaves. In other cases, Cherokees were shot and killed, (and) some scalped.”[4]

Lenoir noted without specifying where this happened, “One of the Guilford men, Samuel Curry, was left behind sick, was killed and scalped.”[5] Two of the men left here in Nĭkwăsĭ´ had died in the interim as well. The next day the army crosses the river back toward Davidson’s Fort where the campaign started (now Old Fort, east of Asheville), completing the route that becomes known as the Rutherford Trace.

Lenoir doesn’t bother to state the obvious: Before leaving, they burn the town of Nĭkwăsĭ´ and destroy its entire food supply.

If you would like to follow the 100-mile loop taken by the army to the next sight on the Cherokee Campaigns Tour, use Rutherford Trace Route 4.

Historical Tidbits

A story that would seem fiction if not for ample evidence had its climax here. A Scottish aristocrat, Sir Alexander Cuming, landed in Charleston in December 1729. He swindled a number of residents, and headed for the frontier at a time of increasing tension between British settlers and the Cherokees. He worked his way from the Lower to the Upper Cherokee Towns convincing village chiefs to obey King George II—and him as the king’s supposed delegate. He had them gather here at Nĭkwăsĭ´. Cuming somehow convinced them to elevate a man named Moytoy to “Emperor,” a role that had never existed, who would answer to Cuming and hence the king. On Friday, April 3, 1730, “‘there was Singing, Dancing, Feasting, making of Speeches, the Creation of Moytoy Emperor, with the unanimous Consent of all the head Men assembled from the different Towns of the Nation, a Declaration of their resigning their Crown, Eagles Tails, Scalps of their Enemies, as an Emblem of their all owning his Majesty King George’s Sovereignty over them…’”[6] Furthermore, he got seven warriors to travel back to London with him, where they signed a treaty that established British sovereignty, trade relations, and settlement rights. For his efforts, Cuming got nothing, and he eventually spent 20 years in prison for the Charleston con.

A story that would seem fiction if not for ample evidence had its climax here. A Scottish aristocrat, Sir Alexander Cuming, landed in Charleston in December 1729. He swindled a number of residents, and headed for the frontier at a time of increasing tension between British settlers and the Cherokees. He worked his way from the Lower to the Upper Cherokee Towns convincing village chiefs to obey King George II—and him as the king’s supposed delegate. He had them gather here at Nĭkwăsĭ´. Cuming somehow convinced them to elevate a man named Moytoy to “Emperor,” a role that had never existed, who would answer to Cuming and hence the king. On Friday, April 3, 1730, “‘there was Singing, Dancing, Feasting, making of Speeches, the Creation of Moytoy Emperor, with the unanimous Consent of all the head Men assembled from the different Towns of the Nation, a Declaration of their resigning their Crown, Eagles Tails, Scalps of their Enemies, as an Emblem of their all owning his Majesty King George’s Sovereignty over them…’”[6] Furthermore, he got seven warriors to travel back to London with him, where they signed a treaty that established British sovereignty, trade relations, and settlement rights. For his efforts, Cuming got nothing, and he eventually spent 20 years in prison for the Charleston con.- As part of a campaign during the French & Indian War, a force of 1,500 British regulars and Native American troops, plus 1,000 colonial militia, converged here on Tuesday, June 9, 1761, after separate actions. While camped for three days, they used the townhouse as a hospital for 53 men wounded in an ambush. They, too, destroyed the town and crops before marching north.

More Information

- Beadle, Michael, ‘Rutherford Trace: Local Historians Examine the Legacy of a Shock-and-Awe Revolutionary War Campaign against the Cherokee’, Smoky Mountain News, 2006 <https://www.smokymountainnews.com/archives/item/13169-rutherford-trace-local-historians-examine-the-legacy-of-a-shock-and-awe-revolutionary-war-campaign-against-the-cherokee> [accessed 5 April 2020]

- Cucumber, Devin, Cherokee History, In-person interview, Cherokee, N.C., 8/27/2020

- Dean, Nadia, A Demand of Blood: The Cherokee War of 1776 (Cherokee, N.C.: Valley River Press, 2012)

- Dells, William, ‘A Journal of the Motions of the Continental Army Commanded by the Honble. Griffith Rutherford Esqr. Brigadear Generall Against the Cherokee Indians’, 1776, The Filson Historical Society, Arthur Campbell Papers, Mss. A C187 26, William Dells Military Journal <https://filsonhistorical.org/wp-content/uploads/FHS-Mss-A-C187-26-William-Dells-Military-Journal.pdf> [accessed 26 January 2023]

- Greene, Lance, ‘The Archaeology and History of the Cherokee Out Towns’ (unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, 1996) <https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3304>

- Gulahiyi, ‘Celebrating Nikwasi’, Ruminations from the Distant Hills, 2008 <https://gulahiyi.blogspot.com/2008/05/celebrating-nikwasi.html> [accessed 15 April 2020]

- Hamilton, J. G. de Roulhac, ‘Revolutionary Diary of William Lenoir’, The Journal of Southern History, 6.2 (1940), 247–59 <https://doi.org/10.2307/2191209>

- McGibney, Ian, ‘Cuming, Sir Alexander’, NCpedia, 2013 <https://www.ncpedia.org/cuming-sir-alexander> [accessed 15 April 2020]

- Middleton, T. Walter, Qualla, Home of the Middle Cherokee Settlement: Tales of the Great Smoky Mountains’ Native Americans (Alexander, N.C.: WorldComm, 1999)

- Mooney, James, Myths of the Cherokee (New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1995) <https://books.google.com/books?id=YU9LpoZq5EwC&lpg=PA49&dq>

- Owle, Freeman, ‘The Nikwasi Mound’, in Living Stories of the Cherokee, ed. by Barbara Duncan (Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998)

- Rozema, Vicki, Footsteps of the Cherokee: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation, Second (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 2007)

- Stone, Jessi, ‘Protecting the Past: Mounds Hold Key to Understanding Cherokee History’, Aug 3 20116 <https://www.smokymountainnews.com/archives/item/18153-protecting-the-past-mounds-hold-key-to-understanding-cherokee-history> [accessed 10 April 2020]

- ‘The Rutherford Trace and the Destruction of Nikwasi’, NC DNCR <https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2013/09/10/the-rutherford-trace-and-the-destruction-of-nikwasi> [accessed 16 April 2020]

[1] Cucumber 2020.

[2] NC DNCR.

[3] Mooney 1995.

[4] Beadle 2006. Time of arrival from Dells (1776).

[5] Hamilton 1940 (spelling updated).

[6] Gulahiyi 2008.

[a] Middleton 1999.

[b] Dean 2012.

← Cowee/Watauga | Cherokee Tour | Black Hole →