Militia Burn a Cherokee Center

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.2664, -83.4218.

Type: Stop

Tour: Cherokee

County: Macon

A viewing platform and information panel provides the closest access to Cowee Mound, site of an important Cherokee center prior to the American Revolution.

The sight is not marked at the highway (as of April 2023). As you near the coordinates, look for an old-style rail fence on the river side of the road. If you are approaching from the direction of Franklin (heading north), it is not far past the state historical marker you will pass on your right.

The platform has a wheelchair ramp.

Context

State-troop commanders from the Carolinas and Virginia have launched coordinated campaigns to destroy Cherokee settlements, in retaliation for a series of attacks on European-Americans living on Cherokee lands during the Summer of 1776.

State-troop commanders from the Carolinas and Virginia have launched coordinated campaigns to destroy Cherokee settlements, in retaliation for a series of attacks on European-Americans living on Cherokee lands during the Summer of 1776.

Situation

Cherokee

Warned by residents fleeing west ahead of the North Carolina army, those who cannot fight have crossed over the mountains to refuge, while most of the men await the army on the Black Hole approach to the main crossing at Wayah Gap.

Patriot Militia

The army of Brig. Gen. Griffith Rutherford marched from Davidson’s Fort east of modern Asheville and occupied Wata´gi north of today’s Franklin, which it then burned to the ground.

Date

Wednesday, September 11, 1776.

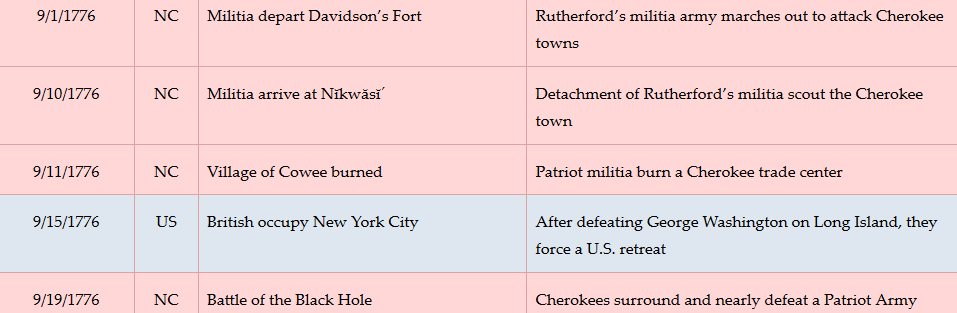

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

Walk to the platform, read the information panel if you like, and look across the river to Cowee Mound. In summer you can barely see it, a grassy arc behind the treetops across the river and below forest-covered Hall Mountain in the background. For a better view, walk up the driveway and stand near the road.

The Cherokee towns and villages operated more like a collection of independent city-states than a single government. In front of you spreads their trade center, Kawiyi, now called “Cowee.” It was named for the Deer Clan, whose peace-making skills made Kawiyi a center for diplomacy as well. A book of Cherokee stories says this was the Cherokees’ first town on the “Tanise,” now called the Little Tennessee River.[1]

The Cherokee towns and villages operated more like a collection of independent city-states than a single government. In front of you spreads their trade center, Kawiyi, now called “Cowee.” It was named for the Deer Clan, whose peace-making skills made Kawiyi a center for diplomacy as well. A book of Cherokee stories says this was the Cherokees’ first town on the “Tanise,” now called the Little Tennessee River.[1]

Just a year before the militia invasion, naturalist William Bartram described what he found, overstating the town’s political importance: “This settlement is esteemed the capital town; it is situated on the bases of the hills on both sides of the river, near to its bank, and there terminates the great vale of Cowe(e), exhibiting one of the most charming natural mountainous landscapes perhaps anywhere to be seen.” He said there are more than 100 homes lining both banks. Contrary to stereotypes about Native American housing, these were log cabins (see “The Cherokees”). He also wrote that farms “of corn, beans, squash and peaches extended out for two miles in all directions.” Bartram noted that the roads were so worn down from use, his feet hit the sides as he rode his horse on them.[4]

He described an impressive building you would have seen from here. “The council or town-house is a large rotunda, capable of accommodating several hundred people; it stands on the top of an artificial mound of earth, of about twenty feet (high), and the rotunda on the top of it being about thirty feet more, gives the whole fabric an elevation of about sixty feet from the common surface of the ground. But it may be proper to observe, that this mount… is of much ancienter date than the buildings, and perhaps was raised for another purpose.”[a] The mound dates to around 600 C.E., built by unknown predecessors of the Cherokee, though possibly ancestors.

He was inside the council house when “a company of girls, hand in hand, dressed in clean white robes and ornamented with beads, bracelets, and a profusion of gay (ribbons), entering the door, immediately began to sing… and formed themselves in a semicircular file or line, in two ranks, back to back… moving slowly round and round.”[2]

After a 15-minute concert with musicians, a group of young men whooped their way inside holding what today we would see as small lacrosse sticks, two per player. Presumably everyone went out to watch the stickball game, which was a violent affair—the name in Cherokee, “a-ne-tsa,” translates to “little brother to war.”[3] Bartram fails to tell us who won.

However, the entire town is eerily empty this day in 1776.

A dust cloud likely arises along the river on the far side of town, announcing the approach of a scouting party from Rutherford’s army on horseback. They ride through the town, finding only two Natives, and at least some of the men ride away to report back.

That afternoon the rest of the army of 1,800 (minus a detachment) with 1,400 packhorses and artillery arrives. These part-time “militia” soldiers spread out through the village, many probably claiming houses or spots in the council house, given that militia carry no tents. This will be their base camp for the next three days. “Here we found corn, fresh meat, hogs and chicken, and sweet potatoes,” reports Samuel Rayl, who rode here from modern Greensboro.[b]

Small units are sent up- and downriver to attack other villages. Meanwhile horsemen trample the crops or drive the livestock to do so. Finally on the 14th the soldiers set fire to all of the buildings and march out the way they came, headed to Nĭkwăsĭ´ (in modern Franklin) in hopes of meeting up with a similar army from South Carolina.

For a close-up view of the river, take the short trail to the left of the platform.

Historical Tidbits

In movie terms, the events here were a “remake.” A force of 1,500 British regulars and Native American troops plus 1,000 colonial militia arrived here on June 15, 1761, as part of the French & Indian War. They camped across the river and destroyed crops here, but left the homes while detachments were sent out to burn other towns. Ten days later the Redcoats and Natives marched north to destroy towns across the Cowee mountains to the east, leaving the militia here as guards, and returned in late June. On July 2 they burned the town and marched south.

In movie terms, the events here were a “remake.” A force of 1,500 British regulars and Native American troops plus 1,000 colonial militia arrived here on June 15, 1761, as part of the French & Indian War. They camped across the river and destroyed crops here, but left the homes while detachments were sent out to burn other towns. Ten days later the Redcoats and Natives marched north to destroy towns across the Cowee mountains to the east, leaving the militia here as guards, and returned in late June. On July 2 they burned the town and marched south.- An 1819 treaty that turned this area over to the federal government permitted Cherokees to apply for citizenship and one-square-mile plots of land. The highest number of plots, 20, was requested here at Cowee, indicating its importance.[5] The Eastern Band of the Cherokee now own the property.

More Information

- ‘Cowee Heritage’, Cowee Community Development Corporation <https://www.coweenc.com> [accessed 9 April 2020]

- ‘Cowee Mound’, Mainspring Conservation Trust <https://www.mainspringconserves.org/projects/cowee-mound/> [accessed 8 April 2020]

- Cucumber, Devin, Cherokee History, In-person interview, Cherokee, N.C., 2020

-

Dean, Nadia, A Demand of Blood: The Cherokee War of 1776 (Cherokee, N.C.: Valley River Press, 2012)

- Greene, Lance, ‘The Archaeology and History of the Cherokee Out Towns’ (unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, 1996) <https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3304>

- Hamilton, J. G. de Roulhac, ‘Revolutionary Diary of William Lenoir’, The Journal of Southern History, 6.2 (1940), 247–59 <https://doi.org/10.2307/2191209>

- Middleton, T. Walter, Qualla, Home of the Middle Cherokee Settlement: Tales of the Great Smoky Mountains’ Native Americans (Alexander, N.C.: WorldComm, 1999)

- Museum of the Cherokee Indian, Exhibits (Cherokee, N.C., 2020)

- Poquette, Nancy, tran., ‘Pension Application of Samuel Rayl, #S4034’, Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Applications & Rosters, 1834 <http://revwarapps.org/g1.pdf>

- Reynolds, William R., The Cherokee Struggle to Maintain Identity in the 17th and 18th Centuries (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2015)

- Rozema, Vicki, Footsteps of the Cherokee: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation, Second (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 2007)

- Stone, Jessi, ‘Protecting the Past: Mounds Hold Key to Understanding Cherokee History’, Aug 3 20116 <https://www.smokymountainnews.com/archives/item/18153-protecting-the-past-mounds-hold-key-to-understanding-cherokee-history> [accessed 10 April 2020]