Rutherford Launches an Invasion

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.6276, -82.1807.

Type: Sight

Tour: Cherokee

County: McDowell

![]() Full

Full

Although not proven, local tradition backed by some evidence holds that Davidson’s Fort occupied the site where the Mountain Gateway Museum is today. It is possible it was somewhere else nearby.

There is parking at the museum and across the street.

Please see our Hurricane Helene page about likely impacts to this location from the 2024 floods.

Context

From May to July of 1776, Cherokees angered by repeated violations of treaties setting the border for European-American settlements attacked whites from Virginia to South Carolina.

From May to July of 1776, Cherokees angered by repeated violations of treaties setting the border for European-American settlements attacked whites from Virginia to South Carolina.

Situation

Cherokee

Urged to action by northern tribes and the outspoken war chief of one town, Dragging Canoe, Cherokees killed at least 40 people in North Carolina. Many Cherokees did not support their actions. They were living their normal lives in permanent towns throughout the southern Appalachians. Contrary to a fake letter circulated by white settlers, the British tried to prevent the attacks.

Militia

The overall commander of militia in the local multi-county district, Brig. Gen. Griffith Rutherford, gained permission from the North Carolina Council of Safety to retaliate by destroying Cherokee villages—whether or not they were involved in the raids. He gathered various county regiments at Quaker Meadows (modern Morganton) and marched this way.

Date

Saturday, September 1, 1776.

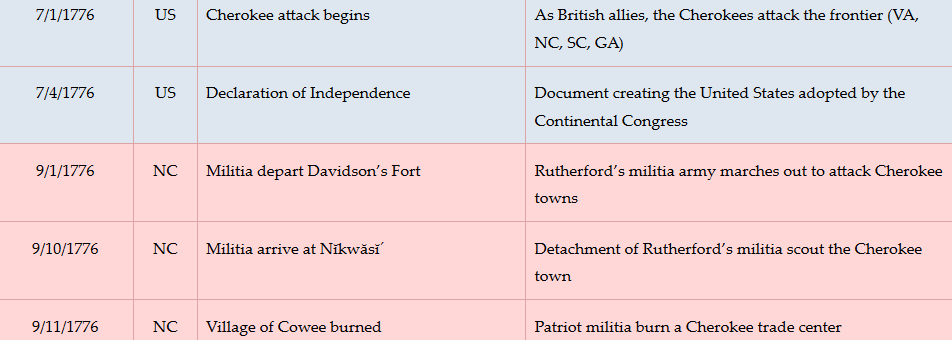

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

Preparing to Invade

Walk into the right side yard of the museum (when facing the back), toward Catawba Avenue, until you can see the front yard by the river.

Around you or likely within your view is a palisade—rectangle of vertical log walls—possibly with a square blockhouse in one or more corners. Inside may be one or more buildings “such as a barracks, officers’ quarters, (and) a magazine for storing powder and weapons.” In addition to the creek, a spring now under the museum building supplies water.[1]

Around you or likely within your view is a palisade—rectangle of vertical log walls—possibly with a square blockhouse in one or more corners. Inside may be one or more buildings “such as a barracks, officers’ quarters, (and) a magazine for storing powder and weapons.” In addition to the creek, a spring now under the museum building supplies water.[1]

The rising tensions with the Cherokees led local part-time militia soldiers under Capt. Samuel Davidson to build the fort to protect local farmers in Spring of 1776, which was completed by May. The location offered access to three Native American trails leading to Salisbury, Virginia, and deeper into the mountains. There was good reason to be concerned: Under a 1767 treaty between the royal governor and the Cherokee, European-Americans are not supposed to be living here.[a] By June a company of militia referred to as “rangers” were stationed here, presumably to scout for warrior bands. Sometime that month Cherokees attacked the fort and drove the rangers out. They retreated to Cathey’s Fort near modern Marion.[2]

Rutherford arrives in August from the direction you are facing with more than 2,000 militia from the county self-defense regiments and volunteers, having camped at Cathey’s Fort on the way. They now make an informal camp all around Davidson’s Fort, roughly a half-mile in each direction. Rutherford may have had them make improvements to the fort. Small militia companies join the army here, along with some natives of the Catawba nation, traditional enemies of the Cherokee.

On Saturday, September 1, Rutherford leaves 300–400 men to protect the region[3] and marches west with around 2,400, including 1,900 soldiers, 80 light cavalry, and 350 pack-horse drivers.[4] The Council of Safety has made sure the forces are well supplied. With them go “nearly 1,400 packhorses, a herd of beef cattle, and a small arsenal that included long rifles, hatchets, and a few small field cannons. Lacking official uniforms, militia members take along their own clothing and many used their own hunting rifles.”[5] The army has six weeks’ worth of supplies.

The men, horses, and cows head toward today’s Asheville bound for a commercial center of the Cherokees at Nĭkwăsĭ´ (modern Franklin), where Rutherford plans to rendezvous with a similar force from South Carolina. They follow the “Suwali-Nunnahi Trail,” from which the name for Swannanoa River and gap is derived. Suwali was the Cherokee word for the Cheraw nation near Charlotte, and the Nunnahi referred to legendary people supposedly living in a mound at Nĭkwăsĭ´.[b]

Return and Results

The army returns here in the first week of October. The exact date is unclear, in part because some units marched ahead, and one appears to have gone straight past to Cathey’s Fort.[c] The combined armies destroyed 52 villages, including 11 by Rutherford’s out of around 40 in North Carolina[6] and modern Tennessee. They followed “a standard tactic—burn every house, cut down or trample the crops, seize or kill livestock, kill any Cherokees that fought back, and move on to the next towns… In some cases, prisoners would be taken and sold as slaves. In other cases, Cherokees were shot and killed, some scalped and, according to one account… a group of women villagers in Burning Town were walled up in a house and burned alive.”[7]

The army returns here in the first week of October. The exact date is unclear, in part because some units marched ahead, and one appears to have gone straight past to Cathey’s Fort.[c] The combined armies destroyed 52 villages, including 11 by Rutherford’s out of around 40 in North Carolina[6] and modern Tennessee. They followed “a standard tactic—burn every house, cut down or trample the crops, seize or kill livestock, kill any Cherokees that fought back, and move on to the next towns… In some cases, prisoners would be taken and sold as slaves. In other cases, Cherokees were shot and killed, some scalped and, according to one account… a group of women villagers in Burning Town were walled up in a house and burned alive.”[7]

An official report stated Rutherford “‘destroyed the greater part of the Valley Towns, killed twelve & took nine Indians, (and imprisoned) Seven White Men, from whom he got four (enslaved) Negroes, a considerable Quantity of Stock & Deer leather, about 100 (weight) of gunpowder & 2000 of Lead…’”[8] Presumably the white men were Tories and/or accused of supplying the Cherokees with weapons. By far the biggest impact was that the bulk of the Cherokee Nation found itself going into autumn and winter in the North Carolina mountains with no homes, livestock, or stored or growing crops.

Many of the men on the campaign go on to fight in key battles in N.C. at various times throughout the war—some on the side of the British! Others, including a few Moravians, tried to remain neutral during the Revolution.

After the expedition, a company is stationed here at all times during the war, with different men rotating through.

Six years to the month after the Rutherford campaign, continuing Cherokee attacks have driven many area colonists into local forts. Thus unable to farm, lack of food has become a problem. Col. Joseph McDowell of Pleasant Garden leads another campaign from Davidson’s.[d] Few details are known. A veteran says the army followed the Rutherford route, but continued beyond where Rutherford had turned at today’s Murphy. Though “‘meeting with no Indian forces of any strength, we destroyed their towns, cut down their corn fields and with the prisoners we commenced our march home and were dismissed sometime in October 1782.’” Another vet says five Cherokees were killed, and a third recalls burning two towns on the Little Tennessee River.[e]

Reproduction Fort

Visit the Gateway Museum if you wish, which features exhibits about mountain life focused on the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Then for help imagining what the fort looked like, take a short drive to visit the reproduction at the privately owned Davidson Fort Historical Park:

To get there:

- From the parking lot, drive out Water Street (away from Catawba Avenue).

- At the end of the block, turn left on Mauney Avenue.

- Drive one block to South Railroad Street, and curve right to follow it (as it becomes Lackey Town Road).

- Drive 0.5 miles to the park, on the left at 173 Lackey Town Road.

The fort is only open for special events, but the outside is visible year-round. It is a best guess at how the original looked, based on eyewitness accounts and standard practices of the day.

If you are taking the Cherokee Campaigns Tour, and want to stay closer to the route taken by Rutherford’s army than your mapping app will provide, follow Rutherford Trace Route 1.

Historical Tidbits

A dramatic arrowhead monument to the fort is on Highway 70 at the intersection with Catawba Avenue. It is off by 20 years on the date of the fort’s construction. Records suggest Capt. Hugh Waddell started a fort in the area in 1756 to protect the Catawbas, allies of the British during the French & Indian War. That was never finished, however.

Perhaps 6,000 people attended the monument’s 1939 dedication, a county history book says. Included were 20 Catawbas and Cherokees, despite the sculpture wrongly showing one of their ancestors in a Plains-tribe headdress. The great-great-granddaughter of the only European-American born at the fort unveiled the monument.[9]

More Information

- Beadle, Michael, ‘Rutherford Trace: Local Historians Examine the Legacy of a Shock-and-Awe Revolutionary War Campaign against the Cherokee’, Smoky Mountain News, 2006 <https://www.smokymountainnews.com/archives/item/13169-rutherford-trace-local-historians-examine-the-legacy-of-a-shock-and-awe-revolutionary-war-campaign-against-the-cherokee> [accessed 5 April 2020]

- Bricker, Jesse, Davidson’s Fort Location, In-person interview, Old Fort, N.C., 2020

- Cashion, Jerry, Old Fort and the North Carolina Frontier (North Carolina Office of Archives and History, 1969) <https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll6/id/5028> [accessed 27 April 2020]

- Chappo, John, ‘Shock and Awe: A Summary Account of Brigadier General Griffith Rutherford’s 1776 Military Campaign against the Cherokee in Western North Carolina and Its Impact on American Westward Expansion’, Saber and Scroll, 5.1 (2016), 14

- ‘Davidson Fort Historical Park’ <https://www.davidsonsforthistoricpark.com/> [accessed 16 February 2020]

-

Dean, Nadia, A Demand of Blood: The Cherokee War of 1776 (Cherokee, N.C.: Valley River Press, 2012)

- Fossett, Mildred, History of McDowell County (Marion, N.C.: McDowell County American Revolution Bicentennial Commission Heritage Committee, 1976)

- Ganyard, Robert L., ‘Threat from the West: North Carolina and the Cherokee, 1776-1778’, The North Carolina Historical Review, 45.1 (1968), 47–66

- Hamilton, J. G. de Roulhac, ‘Revolutionary Diary of William Lenoir’, The Journal of Southern History, 6.2 (1940), 247–59 <https://doi.org/10.2307/2191209>

- ‘History Timeline’ (Town of Old Fort, North Carolina) <http://oldfort.org/Old Fort Timeline Master.xls> [accessed 28 August 2020]

- Jones, Randell, Before They Were Heroes at King’s Mountain, North Carolina/Tennessee Edition (Winston-Salem, NC: Daniel Boone Footsteps, 2011)

- ‘Marker: N-31’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=N-31> [accessed 16 February 2020]

- Martin, Carol, and Martin, Robert, ‘A Short History of Davidson’s Fort (As We Know It So Far)’, Facebook, 2014 <https://www.facebook.com/notes/davidsons-fort-historic-park/a-short-history-of-davidsons-fort-as-we-know-it-so-far/627296674021436/> [accessed 10 April 2020]

- North Carolina Council of Safety, ‘Letter from the North Carolina Council of Safety to Griffith Rutherford, Volume 11, Pages 351-352’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1776 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr11-0223> [accessed 2 May 2023]

- Swann, Anne Landis, The Other Side of the River: The Struggle for the McDowell County Frontier (Morris Publishing, 2010)

[1] Quotation from Martin 2014; spring location from Swann 2010.

[2] History Timeline.

[3] Beadle 2006.

[4] Jones 2011.

[5] Chappo 2016.

[6] Villages destroyed from Dean 2012, the most comprehensive book on the 1776 campaigns; number in North Carolina from Ganyard 1968.

[7] Beadle.

[8] Jones.

[9] Earlier fort, dedication details: Fossett 1976.

[a] Trails from Swann. Treaty line: The 1767 agreement between Royal Gov. William Tryon and the Cherokees placed the border on a straight line from Tryon Peak near today’s Columbus, N.C., to Chiswell’s Lead Mines in Virginia, northwest of modern Mt. Airy (‘Agreement Between North Carolina and the Cherokee Nation Concerning the Boundary Between North Carolina and Cherokee Land Cherokee Indian Nation, Volume 07, Pages 469-471’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1767 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr07-0199>).

[b] Ibid.

[c] According to Lt. William Lenoir (de Roulhac 1940).

[d] Different from a man of the same name from Quaker Meadows (modern Morganton), who was also on the campaign.

[e] Swann.