A Ridge Turns Patriots into Targets

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 34.9225, -79.3350.

Type: Sight

Tour: Tory War

County: Hoke

![]() Full

Full

Park on the shoulder of the road where open woods line the eastern side. This part of the battlefield can be viewed entirely from your vehicle. Two battles were probably fought in the area. This location is from the larger second battle.

Context

With the Continental Army in South Carolina and a British corps in Wilmington, a brutal civil war has erupted between Loyalists and Patriots in the southern sandhills of North Carolina.

With the Continental Army in South Carolina and a British corps in Wilmington, a brutal civil war has erupted between Loyalists and Patriots in the southern sandhills of North Carolina.

First Battle

Some historians say an earlier action, and Beattie’s Bridge, were at another location north of here, near Aberdeen. We follow the conclusion of the State Library of North Carolina’s NCpedia entry, co-written by a leading state historian, which places both here[a]. Still, believe with caution!

Beattie’s Bridge (or Beatti’s or Bettis’) over Drowning Creek, now called the Lumber River, may have been the scene of a battle in August 1781. Few details are known, however, all drawn from the official report by Patriot Col. Thomas Wade to Gov. Thomas Burke.[2] Wade says the battle resulted from Loyalist Col. “Old” Hector McNeill’s “flying army” taking Patriot (“Whig”) men and possessions between this river and the Pee Dee west of here.

He may have had a more personal reason. A Loyalist or “Tory” force had surprised a small unit camped with Wade at Piney Bottom Creek (now on Fort Bragg) in a pre-dawn raid that killed seven. One of those casualties was a small boy who pleaded for his life but was killed with a broadsword, infuriating Wade.

Whatever the reasons, Wade called out half his men and gave chase.

This page starts with a second battle here, fought by many of the same men.

Second Battle

Loyalist

A month later, McNeill and his 70 part-time “militia” soldiers are searching for a Patriot force that captured some of his men in a raid three days earlier. Meanwhile, Col. David Fanning has made a supply run from his Cox’s Mill base (near modern Ramseur) to Wilmington. On the way back he has camped at McPhaul’s Mill eight miles away with around 155 men. Fanning offers to help McNeill, who is happy to accept and puts Fanning in charge.

Patriot

A Patriot militia force of 600–660 under Wade drove back Tory pickets stationed on the bridge.[1] It then camped on a ridge between that and Little Raft Swamp, knowing more Tories are in the area.

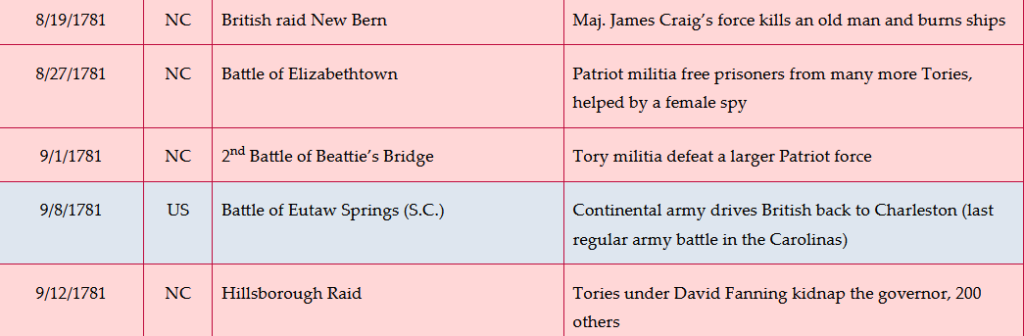

Dates

- First Battle: Saturday, August 4, 1781.

- Second Battle: Saturday, September 1, 1781.

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

A Redcoat on the Ridge

The exact location of the fighting is not proven, but this area of the hill seems highly likely given eyewitness descriptions, topography, known landmarks, and the nearby road named after one of the Loyalist leaders—suggesting local tradition associates the vicinity with him!

The exact location of the fighting is not proven, but this area of the hill seems highly likely given eyewitness descriptions, topography, known landmarks, and the nearby road named after one of the Loyalist leaders—suggesting local tradition associates the vicinity with him!

Look into the woods on the east side of the road (the right side if U.S. 401 is behind you).

Patriot militia in plain clothes have spread out into a line on this side of the ridgeline, perhaps where the road now runs. There are only a few pine trees on top of the hill and little undergrowth on this relatively flat hilltop, so they have no protection. They have waited through the morning. Suddenly around 11 a.m., a shot rings out down the hill to the east.

Fanning was hoping to surprise the Whigs and had almost gotten his men into a line of attack on horseback. Unfortunately for him, one of his men fell or was thrown from his horse, and his gun went off. It’s unclear why the Patriots do not see them. The Tories must be within tree cover downslope, similar to the thicker woods you see today.

The Patriots fire a volley immediately, and eighteen Loyalists fall, literally: Their horses have been shot. The Whigs must have assumed the Tories were on foot. Militia traveled by horse, but usually fought dismounted.

The numbers could have been higher. Outnumbered, Fanning has spread his men far apart, both to seem like he has more and to prevent being flanked. So many of the Patriot bullets whiz through empty air.

Perhaps you hear Fanning order his men to dismount. They move into view in a line with gaps between them, and open fire. The two sides exchange shots for around 90 minutes. Lead balls whizz past you and smoke swirls.[3]

Finally Fanning orders an uphill charge while volleying. That is, he orders them to fire, advance toward you as they are reloading, fire again, and so on.[4] Fanning, resplendent in his official British uniform awarded him in Wilmington, remains on his horse and leads the way. Oddly, no Patriot manages to shoot Fanning, despite his being between the lines, on a horse, in a red coat! They may have tried: Recall that these are not trained soldiers, and few if any had more-accurate rifled guns.

Soon you can see a problem, despite the Whigs’ greater numbers. Even if they kneel to load, every time one of them stands up to fire, they are exposed and easy to target against the sky. The Loyalists blend in more with the trees behind them. Meanwhile, the Patriots are making a common mistake of aiming too high when shooting downhill. Finally, they are more tightly bunched together. So they are taking heavier losses than are the Tories, and become increasingly panicked.

The Loyalists get within 25 yards. Wade decides he cannot win and orders a retreat. His soldiers do not need encouragement; they break out of formation and run down the back side of the hill, toward a wagon road where US 401 is now. Fanning on horseback and his soldiers on foot sprint past you and after them. But he stops them somewhere down the hill, and orders them back to get their horses. After a time they ride off in pursuit.

Fanning is furious: He had sent McNeill to the south of the hill with orders to join Fanning only if Fanning’s troops got into trouble. But most of McNeill’s troops are still somewhere too far east or south to block the retreat. Fanning probably realized what had happened when he saw the Whigs getting away, which would explain why he sent his men back for their horses.

Crossing Out of Danger

Follow the retreat:

- Drive down Gainey Road to U.S. 401.

- Turn right, and drive to the bottom of the hill just before the Lumber River.

- Turn right at the entrance to the Wagram Boating Access Area.

Either drive on the old pavement to the left, bearing in mind there is no turnaround, or park in the lot and walk to the bridge at the end of the pavement.

The 1922 bridge in front of you is likely where the wooden Beattie’s Bridge was in 1781. This is where the Tories brushed back by Wade earlier would have been stationed.

The 1922 bridge in front of you is likely where the wooden Beattie’s Bridge was in 1781. This is where the Tories brushed back by Wade earlier would have been stationed.

Turn around and look the way you came.

At the end of the battle, when the retreating Patriots approach this spot, they get a nasty surprise: McNeill has posted some of his Loyalists here in front of the bridge.[5] However, it is a small enough force that the Whigs in front run right at them and fight their way through. Now Wade’s entire army rides or runs past you down the road as the remaining Tories scramble out of the way.

You may wish to cross the bridge to get a better sense of what the road was like in those days.

After a delay, Fanning’s men ride past you as well. They pursue the Patriots for up to seven miles from here, capturing 54 of them.

After viewing the Battle Map, continue below it to the section on the earlier battle that probably took place here.

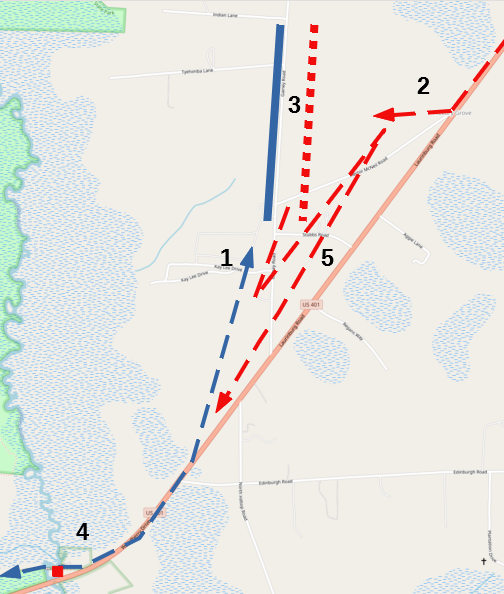

Battle Map

The Second Battle of Beattie’s Bridge. All locations except bridge are approximate. 1) Patriots push through Tory resistance at the bridge and occupy the nearby hill. 2) Tories approach and spread their line, trying to surprise the Patriots. 3) Accidental gunshot blows surprise; the lines exchange fire until the Tories charge. 4) Patriots retreat, again through Tories. 5) Tories chase on foot, go back for their horses, and continue pursuit.

First Battle

It is dusk a month earlier, Saturday, August 4. Patriots approach from farther down the road. Wade has sent a few men forward to capture this “‘pass, which is a very dangerous one, being a narrow lane and swamp very thick,’” Wade reports later. They halt here. One of the Tories guarding the bridge comes across and is captured. (Recall that militia do not wear uniforms, just their everyday clothing.)

It is dusk a month earlier, Saturday, August 4. Patriots approach from farther down the road. Wade has sent a few men forward to capture this “‘pass, which is a very dangerous one, being a narrow lane and swamp very thick,’” Wade reports later. They halt here. One of the Tories guarding the bridge comes across and is captured. (Recall that militia do not wear uniforms, just their everyday clothing.)

From him, Wade learns the Tories are encamped on high ground on their side—probably not the same ridge you just visited, but one to the south beyond US 401. Wade orders his men across.

If you are on the west side of the bridge, follow them back onto it.

More Whig militia appear up the road, and all begin crossing the bridge. However, the disappearance of the Tory guard apparently alerted the Loyalists: They have moved more men up to the other side of the bridge. By now it is probably dark. As the Whigs cross, the Tories open fire, and the Patriots fall back. For about an hour the two sides exchange fire, but the Patriots eventually force their way across the bridge.

Continue back to the east side of the bridge.

The Tories panic and break. There is a cornfield surrounded by fences, probably on the far side of US 401. The Patriots pour bullets into the Tories until the rest of the Tory force begins to surround them. The Whigs pull back across the bridge, but not before some are captured. Wade says, “‘our party saw seven (Tories) dead in the lane and a great deal of blood on the fences…’”

The two sides resume shooting at each other across the bridge until around midnight. The Tory firing slacks off, and Wade suspects they are trying to entice his men into an ambush. Plus, the Patriots are nearly out of ammunition. So Wade orders a retreat.

A Patriot participant, one of the captured, reported years later that he and the other prisoners were taken to the British in Wilmington.[6]

Casualties

First Battle

- Loyalist: 12–13 dead, 15 wounded.

- Patriot: 0–1 dead, 4 wounded, unknown captured.

Second Battle

- Loyalist: 1 killed, 4 wounded.

- Patriot: 23 killed, up to 4 wounded, 54 captured (4 of whom died).

After the Second Battle

The Tories also captured 250 horses laden with goods pilfered from Loyalist homes. As usual when there is no chance of figuring out what belongs to whom, Fanning institutes the “finders, keepers” rule. However, he first uses the ill-gotten goods to equip 50 men who did not have horses. He paroles some of the captive Whigs—meaning they are free as long as they agree not to fight again—but sends 30 of them to the British in Wilmington under guard.[7]

More Information

- Butler, Lindley, and Henry McKinnon, ‘Bettis’s Bridge, Battle Of’, NCpedia, 2006 <https://www.ncpedia.org/bettiss-bridge-battle> [accessed 27 January 2020]

- De Van Massey, Gregory, ‘The British Expedition to Wilmington, North Carolina, January-November, 1781’ (East Carolina University, 1987)

- Dunkerly, Robert M., Redcoats on the Cape Fear: The Revolutionary War in Southeastern North Carolina, Revised (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2012)

- Fanning, David, The Narrative of Colonel David Fanning (New York, NY: Reprinted for Joseph Sabin, 1865) <https://archive.org/details/toryintherevolu00fannrich/page/n8/mode/2up>

-

Graham, William A. (William Alexander), General Joseph Graham and His Papers on North Carolina Revolutionary History (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton, 1904) <http://archive.org/details/cu31924032738233> [accessed 27 March 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Beatti’s Bridge’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2012a <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_beattis_bridge.html> [accessed 27 January 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Little Raft Swamp’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2012b <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_little_raft_swamp.html> [accessed 27 January 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Piney Bottom Creek’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2010 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_piney_bottom_creek.html> [accessed 28 January 2020]

- ‘Marker: I-50’ <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=I-50> [accessed 27 January 2020]

- McPhaul, John Henry, ‘The Battles of McPhaul’s Mill and Raft Swamp, 1781’, Cape Fear Clans, 1974 <http://www.capefearclans.com/ColonialMuster.html> [accessed 26 January 2020]