Continentals Camp before and after Guilford

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 36.3072, -79.7378.

Type: Sight

Tour: Guilford Battle

County: Rockingham

![]() Full

Full

The coordinates mark a wide shoulder you can park on safely, directly northeast of a bridge over Troublesome Creek. (If you drive from US 158, you are headed north and east is to your right; if from Reidsville, this is on the left before the bridge).

There are no remains of the Revolutionary-era features on this page, so you can stay in your vehicle. Visiting one of the sites requires an off-trail walk through the woods. The land is owned by the county historical association.

Context

The Continental Army of Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene headed for Virginia to elude the British temporarily in early 1781, but ten days later it re-entered North Carolina, and the British Army moved out of Hillsborough to confront it.

The Continental Army of Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene headed for Virginia to elude the British temporarily in early 1781, but ten days later it re-entered North Carolina, and the British Army moved out of Hillsborough to confront it.

Situation

Continental/Patriot

Greene constantly shifted position to avoid Cornwallis while gathering supplies and, more importantly, part-time soldiers called “militia.” He wants to fight, but do so with enough men, and on the ground of his choosing: the terrain west of Guilford Court House, ten miles away in today’s Greensboro. Cavalry and fast-moving infantry screen his movements.

British/Tory

Cornwallis keeps his army on the move as well, trying to pin Greene down for the kill. His cavalry constantly tries to find and harass the Americans.

Dates

Tuesday, February 13–Tuesday, March 20, 1781.

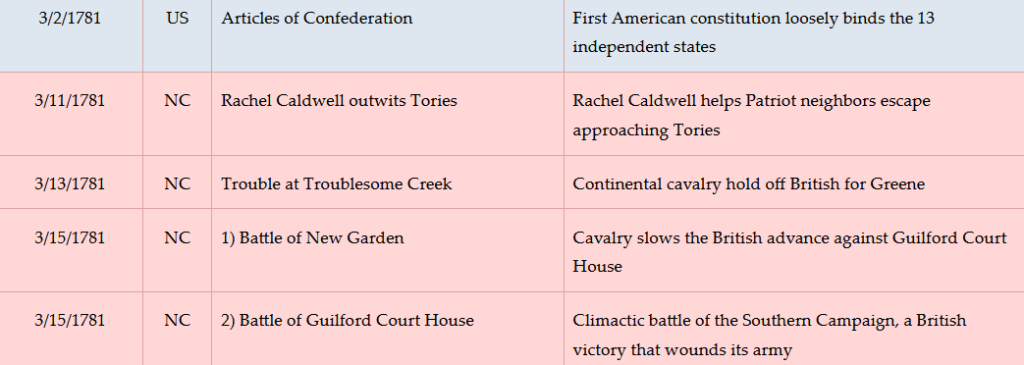

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

The Continentals Arrive

Look into the woods to the east, past the post-Revolution mill dam.

Established as “Speedwell Furnace” in 1770, the Troublesome Iron Works is a complex of buildings for smelting iron from raw ore. Zoom in on the Location map, and look along the creek to the right from the bridge, down a curve, and then up to the bend above the bridge. The complex was just above the upward loop of the creek, between the first sharp right curve and the lesser one beyond it.[1] (Souvenir hunters should note the area has already been thoroughly looted.)

On Tuesday, February 13, 1781, Greene’s army of more than 2,000 men with horses, wagons, camp followers, and four cannons marches north up today’s Monroeton Road, then a dirt wagon road. The army had camped at Guilford Court House, and Greene saw it was excellent ground for a defensive battle. However, unable to gather enough militia to fight Cornwallis, they are headed for the Dan River and Virginia.

They camp around the ironworks and on the heights above. The next morning they move out, except for the cavalry of Lt. Col. “Light Horse” Henry Lee. Lee’s troops remain at the site facing across the creek.

Confrontations and Confidence

If you wish, walk to the bridge and face across it.

Some sources suggest part of the British army appears on the far side of the creek later that day and halts. The officers decide to try to drive Lee off with artillery placed in the road. No one knows where this happened, but one source claims it is here that a Patriot, Tom Archer, steps into the road and yells, “I wish you would take that ugly thing out of the road, or it may cause some trouble…” He supposedly asks permission to shoot the artilleryman. But he is told to hold his fire until the Redcoat is about to light the cannon fuse, as the goal is to stretch out the delay of the British. This story says he steadies his rifle on a tree, and at the last moment shoots the man.[2]

Some sources suggest part of the British army appears on the far side of the creek later that day and halts. The officers decide to try to drive Lee off with artillery placed in the road. No one knows where this happened, but one source claims it is here that a Patriot, Tom Archer, steps into the road and yells, “I wish you would take that ugly thing out of the road, or it may cause some trouble…” He supposedly asks permission to shoot the artilleryman. But he is told to hold his fire until the Redcoat is about to light the cannon fuse, as the goal is to stretch out the delay of the British. This story says he steadies his rifle on a tree, and at the last moment shoots the man.[2]

Turn around and look up the hill.

After two hours, Lee decides to move out, having succeeded at giving Greene more of a head start. His force mounts up and rides over the hill. The British then move into Greene’s former campsite, and follow in the Continental footsteps the next day.

After only a week camped north of modern South Boston, Va., Greene recrosses the river and returns to the region. For the next two weeks, the army will spend no more than two nights in any one camp, to avoid a direct confrontation with Cornwallis until Greene is ready.

Greene’s army returns from the north on Sunday, March 11. It had camped the night before at High Rock Ford a few miles downriver. The next day the entire army marches back the way it came to the ford, to pick up more militia units, and another night later they return here—this time from the south!

Entrenchments may have been built on the rise to the north during these stays.[3] If so, these served both as protection from an unlikely attack from the north and as a second line of defense and artillery position for an attack from the south.

Now, however, he has all of the troops he can expect. After one more night here, they march south again at 6 a.m.[4], headed for Guilford Court House to await Cornwallis. (One source suggests they take the route now marked by NC 150 through modern Hillsdale to Lake Brandt Road.[5]) Camp followers remain here, along with the baggage wagons.[a]

Look across the creek again.

Around dawn on Friday, March 16, a cold rain is coming down. Streaming up Monroeton Road comes Greene’s exhausted army of Continental soldiers and militia, minus their cannons. They are returning from a bloody battle at Guilford Court House, the largest of the war in North Carolina. A hospital likely would have been located in one of the iron works buildings to treat the mobile wounded. A line of sentries is placed along this side of the creek, which combined with the earthworks and the ironworks pond to the east would have made this a good defensive position if Cornwallis followed him—as Greene thought he would.

Technically Greene lost the battle because he was driven from the field. However, despite their losses, the men know they have hurt Cornwallis badly. This day, Greene writes another general, “‘Our army are in the highest spirits, and wishing for another opportunity of engaging the enemy.’”[6] Instead, an officer with a white flag rides out with a surgeon headed back to the battlefield, to help treat the many wounded left there. Greene and Cornwallis had agreed to this in an exchange of letters.

A couple of days later, Greene writes here of the battle, “‘It was long, obstinate, and bloody. We were obliged to give up the ground, and left our artillery; but the enemy has been so soundly beaten, that they dare not move toward us…’” About the conditions here at the Ironworks he says, “‘We have little to eat, less to drink, and lodge in the woods in the midst of smoke. Indeed our fatigue is great. I was so much overcome night before last (the 16th) that I fainted.’” He predicts, however, that Cornwallis will move off once the wounded are stabilized. Meanwhile, he writes his wife that he has not taken off the clothes he is wearing for six weeks![7]

Greene learns he has hurt the British more than he realized: Cornwallis is retreating toward Cross Creek (modern Fayetteville). The hunted now becomes the hunter. On the 20th, the army decamps and marches back toward the recent battlefield for the last time, intending to chase the British.

Greene learns he has hurt the British more than he realized: Cornwallis is retreating toward Cross Creek (modern Fayetteville). The hunted now becomes the hunter. On the 20th, the army decamps and marches back toward the recent battlefield for the last time, intending to chase the British.

If you wish to visit the ironworks site while reading more about it below, walk into the woods to the left of the mill dam. Continue straight as you pass under transmission lines and reach the creek. Follow the creek to the northernmost (leftmost) point, where it starts to curve back to the right. Look left, away from the creek. The iron works were on the flat and hillside in front of you.

Historical Tidbits

George Washington visited the ironworks manager here, a comrade from the war, during Washington’s tour of the southern states as president in 1791. They shared breakfast. Another visitor that year described what the president would have seen: “the buildings, large reservoir of water, creek, and the people at work, with the noise of the machinery of the mills and the rapid currents which work them, have a pleasing and singular appearance just as you ascend the hill which overlooks them…”[8] Though operated for decades, with their hill mined more than 100 years, the ironworks never were highly successful. The ore in this area was not the right type for making high-quality metal.

George Washington visited the ironworks manager here, a comrade from the war, during Washington’s tour of the southern states as president in 1791. They shared breakfast. Another visitor that year described what the president would have seen: “the buildings, large reservoir of water, creek, and the people at work, with the noise of the machinery of the mills and the rapid currents which work them, have a pleasing and singular appearance just as you ascend the hill which overlooks them…”[8] Though operated for decades, with their hill mined more than 100 years, the ironworks never were highly successful. The ore in this area was not the right type for making high-quality metal.- Troublesome Creek was “so named because it was subject to sudden flooding and difficult to ford.”[9] After the war, upstream dams calmed it. A grain mill was completed in the late 1780s and lasted until 1915, when it burned down, though a replacement operated until World War II.[10] You can see (or passed) the remains of the mill pond dam in the woods. A millstone from the old mill is displayed by the road a little further north of the creek, standing up.

More Information

- Babits, Lawrence, and Joshua Howard, Long, Obstinate, and Bloody: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009)

- Bagley, Carla, ‘Troublesome History’, Greensboro News and Record, 2004 <https://www.greensboro.com/news/troublesome-history/article_ae4952d0-7d13-52e1-af6a-c32a80de83f8.html> [accessed 8 January 2020]

- Butler, Lindley, ‘Troublesome Creek Ironworks’, NCpedia, 2006 <https://www.ncpedia.org/troublesome-creek-ironworks> [accessed 8 January 2020]

-

Caruthers, Eli Washington, Interesting Revolutionary Incidents and Sketches of Character, Chiefly in the ‘Old North State.’ (Philadelphia: Hayes & Zell, 1856) <http://archive.org/details/interestingrevol00incaru> [accessed 23 April 2020]

- Dunkerly, Robert, Women of the Revolution: Bravery and Sacrifice on the Southern Battlefields (Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2007) <https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/12305023> [accessed 1 April 2022].

- EleHistory Research, ‘American Revolution Sites, Events, and Troop Movements’, 2019 <http://elehistory.com/amrev/SitesEventsTroopMovements.htm> [accessed 16 March 2020]

- ‘Founders Online: [June 1791]’, National Archives <http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-06-02-0002-0005> [accessed 8 January 2020]

- Greene, George Washington, The Life of Nathanael Greene: Major-General in the Army of the Revolution (G. P. Putnam and Son, 1871)

- Lewis, J.D., ‘Speedwell’s Furnace’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2010 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_speedwells_furnace.html> [accessed 8 January 2020]

- ‘Marker: J-16’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=J-16> [accessed 14 March 2020]

- Phillips, Harriet, ‘A Landscape Analysis and Cultural Resource Inventory of Troublesome Creek Ironworks: A Geographical and Archaeological Approach’ (unpublished Master’s, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2011) <https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/Phillips_uncg_0154M_10655.pdf> [accessed 11 March 2020]

- Rankin, Hugh F., The North Carolina Continentals (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1971)

- Rodenbough, Charles Dyson, ed., The Heritage of Rockingham County North Carolina 1983 (Wentworth, N.C.: Rockingham Historical Society, Inc. and Hunter Publishing Company, 1983)

[1] Phillips 2011.

[2] The story is detailed by Caruthers (1856) without a location, and he believes the main British army, at least, did not come this far north. Lewis 2010 places the Archer incident here without citing his evidence.

[3] An archaeological study found depressions that could be trenches. But there was no other evidence, perhaps due to souvenir hunters stealing it over the years (Phillips).

[4] Babits and Howard 2009.

[5] Rodenbough 1983.

[6] Greene 1871.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Founders Online.

[9] Barefoot 1998.

[10] Butler 2006.

[a] Dunkerly 2007.