Continentals Make their Escape

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 36.6918, -78.9041.

Type: Sight

Tour: Guilford Battle

County: Halifax, Va. (Closest in N.C.: Person)

![]() Partial

Partial

The coordinates mark our second stop, because most visitors will prefer to start there.

The first stop, Irvine’s Ferry, is a 5-mile roundtrip walk beginning nearby. All of the stories known about the actual crossing probably happened at Irvine’s. The trail, on a former railroad grade, is wide and flat with light gravel. If up for that, use these coordinates to go to where Lomax Avenue ends at the Tobacco Heritage Trail: 36.6958, -78.9165. Then see the directions under “Irvine’s Ferry” below.

Otherwise, park at the map coordinates above for Boyd’s Ferry, where a dirt road ends at the Dan River, and walk over to the monument to read the stories from both ferries. (Or just stay in your vehicle.)

The third stop can be partially seen from a sidewalk, but a view of the ford it describes requires going down a few steps without handrails.

Context

After losing many men as prisoners at the Battle of Cowpens in South Carolina almost a month earlier, the British Army has chased the Continental Army across North Carolina and is trying to trap it against the Dan River in Virginia.

After losing many men as prisoners at the Battle of Cowpens in South Carolina almost a month earlier, the British Army has chased the Continental Army across North Carolina and is trying to trap it against the Dan River in Virginia.

Situation

British

The British army of Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis was camped near modern Greensboro, N.C. Cornwallis knew the Patriots were trying to get across the Dan, so they could resupply and gain reinforcements. He sent forward the brigade of Brig. Gen. Charles O’Hara to try to delay or trap the Patriots, and ordered the rest of his army to follow behind.

Continental/Patriot

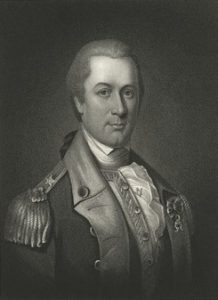

Maj. Gen. Daniel Morgan, the victor at Cowpens, had barely escaped at two major river crossings in North Carolina with help from his commander, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene. The forces of the two men combined at Guilford Court House (now in Greensboro). Greene hoped to make a stand against Cornwallis there, but could not collect enough troops and supplies. He and his officers crafted a plan in a “council of war.” Greene formed a “light corps” of cavalry and infantry soldiers that could move quickly to screen his actions. Morgan, badly ill, went home, so the corps command passed to Col. Otho Williams.[1] Greene then sent the main army toward the Dan.

Date

Wednesday, February 14, 1781.

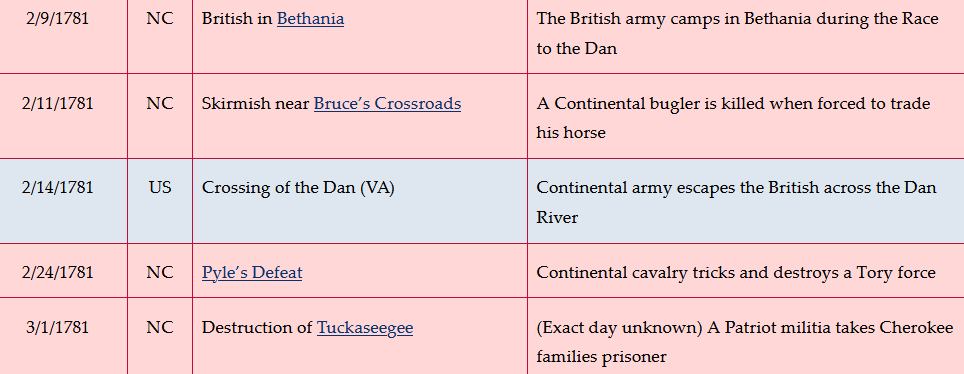

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

Irvine’s Ferry

If you are going to Irvine’s, walk past the gate, turn right, and take the Tobacco Heritage Trail to these coordinates: 36.6893, -78.9609. (Despite the gate’s “No Trespassing” signs, the trail is open to the public.) The ferry location is not marked on the trail. The coordinates are at a short bridge, however.

For those reading at Boyd’s Ferry in South Boston, translate “here” to a rural area about 3 miles to your right when facing the river, with a wooded slope to the right; wide, flat bottomlands to the left; and the far riverbank barely visible beyond them in the distance.

Eyewitness accounts written years later contradict each other and accounts from the time on the dates and locations of these events. We defer to Greene’s orders and letters in those cases.[2]

James Irvine, Sr., established a ferry here in 1755, the same year his son James, Jr., was born at their home on the far side of the river.[3] What looks like a very wide ditch uphill of the trail bridge, with high banks on either side like a creek, is the northern access road for the ferry.

James Irvine, Sr., established a ferry here in 1755, the same year his son James, Jr., was born at their home on the far side of the river.[3] What looks like a very wide ditch uphill of the trail bridge, with high banks on either side like a creek, is the northern access road for the ferry.

The ferry was probably a flat-bottomed wooden boat or barge wide enough to carry a wagon, attached via loops to a rope that was secured to trees or posts on both banks, to keep the boat from drifting downstream. By 1781, James, Jr., and his two brothers had taken it over, along with the land. (Some modern sources and signs call this “Irwin’s Ferry,” because Greene did in his letters, but he got it wrong!)[4] James filed many claims with the new Commonwealth of Virginia to be paid for ferry crossings related to the war, and for meat, grain, and pastures for horses.[5]

The ferry boat is not alone today, a cold, drizzly Wednesday, February 14, 1781. Probably crowded on the far side are several others, either large rowboats or perhaps more flat-bottomed barges like the ferry boat. With them on that side is the man in charge, Lieut. Col. Edward Carrington, Greene’s quartermaster-general (chief supply officer). Carrington lived in this region, but was in Hillsborough, N.C., the prior October when Greene passed through on the way to taking over the southern Continental Army. Greene ordered Carrington to survey the Dan as a possible supply route. Carrington wrote Greene later that he had a man canoe up the river to do so.

In the war council at Guilford, Carrington told Greene there was a ferry near today’s Danville, Va., but Cornwallis was about as close to that as the Continentals were. Carrington reported there were only four other large boats between that one and Boyd’s Ferry, and suggested gathering all to cross here and at Boyd’s instead.[6] A militia unit was sent ahead to collect the boats, and maybe store them somewhere upstream so they would not give away the planned location for the crossing.[7] Now most are probably in the river below you, though it is possible one or more were sent to Boyd’s to join the ferry boat there.

Depending on the time of year, you may get a better view of the riverbank and bottomlands a little further down the trail.

Finally around mid-day on the 14th, the first of the Continentals arrive and flow down the opposite side into the ferry and nearest boats. The wagons are sent across first, the last arriving on this side around 2 p.m. Then the men, numbering around 900, begin to cross. Almost all are regular army soldiers from Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia, including dozens of African-Americans. Only around 80 of the part-time soldiers called “militia” came with them, of the roughly 1,000 with the army just five days earlier.

No records leave an exact description of the crossing. Lt. Col. “Light Horse” Henry Lee hints in his memoir that multiple boats could leave at once.[8] Perhaps as the first boats clear the far bank full of soldiers others move into place, more men file in, and a ballet of boats dances before you.

On this side the men flow uphill into the woods and set up a temporary, tentless camp alongside the road. Greene writes Williams at 4 p.m., “I have not slept four hours since you left me, so great has been my solicitude to prepare for the worst.” Finally, at 5:12, he writes again: “All our troops are over and the stage is clear.” When Williams gets the message and informs his troops, they cheer so loudly that the nearby British hear them!

Williams’ corps had been faking as if headed to Dix Ferry near modern Danville, 25 miles upstream from Irvine’s (to your right when facing the river). After allowing what he hoped was enough time for the main army to escape, Williams had turned directly this way. Lee’s cavalry trailed behind to protect the foot soldiers.

Greene orders Williams to send his infantry here to cross over. Lee was to cross at Boyd’s Ferry. Greene posts artillery on this bank facing across, and some troops get behind earthworks thrown up by men sent ahead. Remains were still visible on this side into the early 1900s.[9] More soldiers are on the other side, possibly behind more earthworks,[10] ready to defend against the British if they show up before the light corps can escape.

The light corps arrives just before sunset, perhaps 45 minutes after Greene’s order was sent.[11] In 24 hours Williams’ 100 men had marched 40 miles. The crossing process restarts, continuing into the moonless night by torch- or firelight. Perhaps never getting his orders, Lee arrives here as the last of the infantry reaches this side.[12] Carrington tells him to have the horses swim across. Some flee in fear, but are rounded up and pushed into the dark water. Not until 9 p.m. do Carrington and Lee cross over in the last boat, Lee says. Carrington orders any boats still on the far side brought to this one and secured to trees.

After the war, Carrington served in the Continental Congress and was the jury foreman in the treason trial of Aaron Burr, who had killed Alexander Hamilton in a pistol duel.

The British Fail Again

Soon after, more sounds float across the river. O’Hara’s men have marched the same 40 miles in 24 hours as the light corps, in hopes of catching it. But the troops on this side cheer, and the Redcoats realize they are yet again too late to catch Greene’s army. What now is called the “Race to the Dan” is over.

Soon after, more sounds float across the river. O’Hara’s men have marched the same 40 miles in 24 hours as the light corps, in hopes of catching it. But the troops on this side cheer, and the Redcoats realize they are yet again too late to catch Greene’s army. What now is called the “Race to the Dan” is over.

The main body of the British army stops short of the river, camping roughly four miles southwest (across and to your right).[13] The regiment of a Scottish unit notes it had marched a total of 169 miles in 10 days.[14] The next day, Cornwallis decides to move off. He seems unsure what to do, zigzagging[15], but ends up heading south to Hillsborough in hopes of gathering more Loyalist militia. He also may feel exposed here against the river, as a South Carolina militia force approaches from the west and North Carolinians from the east.

James Irvine, Jr., reports that at some point he “returned home and found that the British had reached the ferry… kept by himself & his Brothers & had destroyed their farm, burnt their fences, destroyed their crop, killed their stock and at that point had turned back into North Carolina.”[16]

Leaving behind a guard, the rest of the Continental army moves on to our last stop on the 15th. Before leaving, Greene writes of their success to the Continental Congress and Gen. George Washington.[17]

The army returns to its earlier campsite here on the evening of Tuesday the 20th. The next day it reverses the scene from exactly a week earlier, with wagons, cannons and men lining up where you stand to await their turns in the boats. With it are hundreds of Virginia militia, and more are heading south.

The Continental army, formerly the hunted, has become the hunter.

If you walked to Irvine’s Ferry, return to where you started.

On the way back, consider stepping off the left side of the trail into the small clearing at these coordinates: 36.6897, -78.9307. Veer right and take the trail to and past the small metal sign for Diamond Hill Cemetery up the slope. Covering the knoll beyond is a graveyard for enslaved people, with some of the anonymous graves marked by simple field stones.

Once back to your vehicle, use the “Location” coordinates at the top of the page to get to the second stop.

Boyd’s Ferry

Walk past the monument to the edge of the park near the railway bridge. Look across the river.

The colonial government granted John Boyd the right to place a ferry boat here in 1749, which his wife Margaret took over when John died, according to a local history book.[18] Run in 1781 by George Boyd, a colonel of the Virginia militia, it probably crosses at or just this side of the modern bridge. Boyd made payment requests like those of the Irvines for ferrying soldiers and wagons throughout the war.[19] He also has a farm, plus a tavern on the far side about three-quarters of a mile southwest of the ferry.[a] Further south along the approach road is Carrington’s land.[20]

The colonial government granted John Boyd the right to place a ferry boat here in 1749, which his wife Margaret took over when John died, according to a local history book.[18] Run in 1781 by George Boyd, a colonel of the Virginia militia, it probably crosses at or just this side of the modern bridge. Boyd made payment requests like those of the Irvines for ferrying soldiers and wagons throughout the war.[19] He also has a farm, plus a tavern on the far side about three-quarters of a mile southwest of the ferry.[a] Further south along the approach road is Carrington’s land.[20]

Likely near the tavern are buildings for clothing and other supplies for Continental forces, plus a “magazine” used to store powder and ammunition. Men who only served for short stints would come there to “muster in” as militia and be discharged. Various units might be in the area at any time awaiting orders. That’s probably why Greene’s order to collect the boats was brought there.[21]

When James Irvine applied for a government pension years later, he reported that the prior November, Col. Boyd put him in charge of 12 men guarding the stores. Probably just before the Crossing, you could have watched from here as Irvine’s men had five wagons ferried across, taking supplies to safety.[22]

Some portion of the main army crossed here on the 14th. The men likely moved up the near bank and set up a temporary camp like the one at Irvine’s to await orders. The next day, Greene writes Virginia Gov. Thomas Jefferson from “Boyd’s Ferry Camp” that they are, “On the Dan river, almost fatigued to death, having had a retreat to conduct for upwards of two hundred miles, manoeuvring (sic) constantly in the face of the enemy, to give time for the militia to turn out and get off our stores.”[23] He tells Jefferson he is prepared to cross the Staunton (“STAN-ton”) River, north and east of here (to the left when facing the river) if Cornwallis crosses the Dan further upstream. Then he heads north himself, with or trailing this part of his army.

It’s unclear how or when Greene passed through this area to write the Jefferson letter. Then as now, there was no direct road from Irvine’s to Boyd’s. Maybe there was a trail from Irvine’s, which Carrington would have known about, that he took to pick up the men here after sending on the other forces. Or he could have turned off the road from the north to get them. The exact routes taken by the two groups to our next stop are unknown.

Boyd’s Ferry operated until 1854, when it was replaced by a covered bridge just the other side of today’s highway.[24]

A Second Crossing

Go to your car and use these coordinates to reach the next stop, at King’s Bridge Landing: 36.7764, -78.9176.

On the way, consider visiting the South Boston-Halifax County Museum of Fine Arts and History, to see exhibits on the Crossing and other local history. After your mapping app takes you onto Broad Street (U.S. 501 North), drive 0.9 miles to Webster Street and turn left. Drive one long block and turn into the museum lot just past Wilborn Avenue (U.S. 501 South).

At King’s Bridge Landing, park and take the pavement to the canoe launch. Walk down the steps until you can see up the river past the old bridge abutments on the left.

Most of the army continued here to the Banister River from the Dan on the 15th. Unless the river is flooded, you can see water rippling over a shallow section just to the left of the abutment on the far side. This is likely the ford used by the army to cross the Banister on the way to the old Halifax County Courthouse. A road is still visible in woods on private property across the river, leading to Cole’s Ferry on the Staunton. What appears to be a ditch on the near side (again on private property) may be the southern approach road to the ford.

Most of the army continued here to the Banister River from the Dan on the 15th. Unless the river is flooded, you can see water rippling over a shallow section just to the left of the abutment on the far side. This is likely the ford used by the army to cross the Banister on the way to the old Halifax County Courthouse. A road is still visible in woods on private property across the river, leading to Cole’s Ferry on the Staunton. What appears to be a ditch on the near side (again on private property) may be the southern approach road to the ford.

The wagons and cannons are pushed across and up. Hundreds of men exhausted from the rapid travel of the last few days, many barefoot because their shoes have worn out, trudge through icy February water and scramble up the far bank. The effort may have taken three hours or more.

A militia unit is left on the far side to guard the ford, while the light corps camps a mile-and-a-half away. The latter moves back across the morning of the 20th, followed by the main army an hour or two later.

Into Camp

The likely location of the main army camp is approximately a 10-mile roundtrip drive. To read about it at the site, return to your vehicle and go to these coordinates: 36.845, -78.9138.

On the way, after crossing the river, and turning left on Howard P. Anderson Road, look for the first public road on the right, Marion’s Trail. The light corps camped at a plantation just up that road.

As you approach the coordinates, a small cemetery comes into view on the left, past a line of trees near the road that ends at a farm lane. Slow down, and when the shoulder on the left flattens out, pull across the road to park by the cemetery. There is a sharp drop for some distance after the farm lane, so don’t pull off too soon.

Walk near the railroad, or remain in your vehicle. Look into the field on the far side of the tracks, beyond the trees there.

The 1768 Halifax County Courthouse[25] stood about 500 feet west of the modern road and somewhat to your left.[26] The building was a refinished barn! Nearby in 1781 is a food-serving tavern called an “ordinary.”

The 1768 Halifax County Courthouse[25] stood about 500 feet west of the modern road and somewhat to your left.[26] The building was a refinished barn! Nearby in 1781 is a food-serving tavern called an “ordinary.”

The railroad basically marks the route of Cole’s Ferry Road at this point. Given that armies of the day often camped along roads, you are probably in the camp. Another portion may be in the cleared area around the courthouse. Also in the camp are the captives from the Battle of Cowpens that Cornwallis had hoped to rescue. British or Loyalist captives from various places were held near the courthouse at times, usually before getting marched to prisoner of war camps farther north.

On the 15th, as the army settles to bed, Greene writes from “Camp Halifax Courthouse” to the North Carolina legislature. He reassures them he will follow Cornwallis if the British head for Hillsborough, part-time capital of the state. But he warns them to be more careful about whom they draft. One N.C. militia cavalry unit has deserted. He advises, “You must not put arms into the hands of doubtful charactors [sic]: depend upon it they will deceive you in the hour of difficulty.”

Here the soldiers rest over the next few days while Greene sends a flurry of orders and letters. Some go to militia commanders in Virginia and N.C. asking them to raise troops. He also orders a unit down the Dan (which becomes the Roanoke) to destroy any boats Cornwallis could use to cross.[27] Yet he writes someone else he has camped here “in order to tempt the Enemy to cross” the Dan.[28]

Lee and his cavalry get little rest. Greene sends them back across by a different ferry on the 19th, to join up with the South Carolina militia approaching Cornwallis in North Carolina. Lee sends back a message that day informing Greene that Cornwallis is headed for Hillsborough.

Probably among other supplies arriving here during the army’s stay are a big portion of the impressive totals provided to the Patriot cause by 25 women in Halifax County over the course of the war. A local historian calculates these included “380 pounds of bacon; 152 pounds of pork; over 5,681 pounds of beef; over 5,800 pounds of corn; about 397 pounds of corn meal used for making hoecakes for the troops; over 1,000 pounds of fodder and 100 sheaves of oats for animal consumption, and 38 gallons of brandy.”[29]

Lewis Morris, son of a general by that name, writes his father from here that news of the withdrawal “‘will be very alarming to those at a distance, and no doubt censured as a very unmilitary step… (but) I am convinced it was dictated by necessity and conducted with the strictest military propriety.’” He adds it was done without loss, “not even a broken waggon (sic) to show that we were hurried.” Morris complains that the militia were no help, “‘more intent upon saving their property by flight (home) than embodying to protect it.’”[30]

Virginia militia commanders call out their men and Jefferson orders more. Hundreds arrive here or pass through shortly after the army leaves, while others from western counties head directly south.

Greene’s plan to attack Cornwallis is bad news for his wife, Catherine. Up north, she had traveled with him in Washington’s army. A general in Philadelphia writes on the 21st that Catherine learned about Greene’s promotion and move south a few months earlier while at that general’s home in Providence, Rhode Island. It took a “‘good deal of Address’” (talking) to calm her down, he reports.

“‘However, she wisely contrasted the Sensation of Tender Disappointment with all conquering Views of Glory and Heroism.’”[31] Those are indeed the views many have of Nathanael Greene, architect of a strategic withdrawal ending here that is still studied in war colleges today.

Crossing Map

The Crossing of the Dan: March routes are approximate. 1) Main Continental army crosses Dan River at Irvine’s and Boyd’s ferries, daytime, Feb. 14. 2) Light corps and cavalry cross at Irvine’s in the evening; boats are secured to north bank; British vanguard arrives soon after. 3) On Feb. 15, Continental army moves north to Halifax Courthouse and camps. 4) British destroy Irvine properties and withdraw.

Historical Tidbits

- Archaeologists found a Native American village near the wastewater treatment plant northeast of South Boston, one source says. Skeletons had been buried in the fetal position with beads below them. Also found were pottery pieces and food remains indicating residents were growing corn as early as 1400, using hoes of stone. They lived in round, thatch-roofed homes more than 20 feet wide within a stockade.[32]

- Enslaved people in Halifax County planned a revolution in 1802, according to a local history book. The leader, Sancho, tried to recruit a man named Abram, saying the plan was for groups to gather at a tavern and store upon the sounding of a horn on the Christian holiday of Good Friday. Those with weapons were to bring extras for those who didn’t have them, and ammunition would be taken from the store. Planning had begun as early as the prior summer, when Sancho supposedly approached another man and said, “‘Bob, you are a valuable man and I wish for you to join me” to revolt. Bob declined, pointing out that an earlier rising in Richmond had ended with the rebels “destroyed” (37 were hung). Someone revealed the plot, and 18 men and women were tried at the new courthouse near the current one in Halifax on Saturday, May 15, 1802. Sancho and five others were found guilty and hung immediately.[33]

More Information

- ‘A Map of the State of Virginia: Reduced from the Nine Sheet Map of the State in Conformity to Law’, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, 1827 <https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3880.ct003676/> [accessed 4 November 2021]

- ‘John Martin of Halifax County – Part 1’ <http://billdraper.net/html/johnmartin.html> [accessed 27 October 2021]

- ‘The Crossing of the Dan’ <https://www.oldhalifax.com/Crossing/CrossingPage3.htm#The%20Crossing%20of%20the%20Dan> [accessed 30 October 2021]

- Aaron, Larry, The Race to the Dan: The Retreat That Rescued the American Revolution (South Boston, Va.: Halifax County Historical Society, 2007)

- Abercrombie, Janice, and Richard Slatten, trans., Virginia Publick Claims: Halifax County (Athens, Ga.: Iberian Publishing Company)

- Buchanan, John, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997)

- Caruthers, E. W. (Eli Washington), Interesting Revolutionary Incidents and Sketches of Character, Chiefly in the ‘Old North State.’ (Philadelphia : Hayes & Zell, 1856) <http://archive.org/details/interestingrevol00incaru> [accessed 23 April 2020]

- Cecere, Michael, ‘Race to the Dan: “Pushed with Great Expedition”’, Journal of the American Revolution, 2014 <https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/02/race-to-the-dan-pushed-with-great-expedition/> [accessed 7 December 2021]

- Cook, Kenneth, ‘History of Halifax County Courthouses’, Mountain Road Walking Tour, 1972 <http://www.oldhalifax.com/county/CourthouseHistoryCook.htm> [accessed 22 November 2021]

- Dodson, Roger, Property Lines from an Old Survey Book: Halifax County, Virginia 1741 to 1901 (Danville, Va.: VA-NC Piedmont Geneological Society, 1998)

- Eanes, Greg, ‘Public Service Claim Statistical Analysis: Halifax County in the American Revolution as Reflected in Public Service Claims and Other Documents’, 2021

- Eanes, Greg, Cole’s Ferry Road and ‘Old’ Halifax Courthouse in Greene’s Campaign (Halifax, Va.: Town of Halifax, 23 March 2021)

- Edmunds, Pocahontas Wight, History of Halifax, Vol. 1, Narration, Undated

- Edmunds, Pocahontas Wight, History of Halifax, Vol. 2, Documentation, Undated

- Espy, Carl, ‘Greene’s Campsite-“Camp Halifax Court House” North of the Banister’, E-mail, 26 October 2021

- Espy, Carl, Knight’s Bridge Ford and Cole’s Ferry Road and Tour, In-Person Interview, 2021

- Fuller, West, ‘Irwin’s Ferry: Traces Remain Today of Historic Crossing’, The Gazette-Virginian (South Boston, Va., Undated), Local History Room, Halifax-South Boston County Library

- Fuller, West, ‘War’s Turning Point Said at Boyd’s Ferry’, The Gazette-Virginian (South Boston, Va., Undated), Local History Room, Halifax-South Boston County Library

- Gordon, William, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independence of the United States of America (New York: Printed for Samuel Campbell by John Woods, 1801) <http://archive.org/details/historyofrise03gord> [accessed 29 October 2021]

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of Ashur Reaves, S17649’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/S17649.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of Dudley Gatewood, S6873’, 1832 <http://revwarapps.org/s6873.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of Evan Thompson, W2975’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1833) <http://revwarapps.org/W2975.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of James Adams, S16306’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/S16306.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of James Irvine, S4422’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/s4422.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of John Atkinson, W5650’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1834) <http://revwarapps.org/W5650 .pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of John Rainey, S4035’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/S4035.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of Matt Martin, S2726’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1833) <http://revwarapps.org/s2726.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of Richard Oldham, W6887’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/w6887.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of Robert Mims, S30590’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1834) <http://revwarapps.org/S30590.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of William Hatcher, S31727’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/s31727.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of William Lesley (Leslie), S31821’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/s31821.pdf>

- Graves, Will, tran., ‘Pension Application of William Lorance (Lowrance), S31217’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/s31217.pdf>

- Greene, George Washington, The Life of Nathanael Greene: Major-General in the Army of the Revolution (G. P. Putnam and Son, 1871)

- Haiman, Miecislaus, Kosciuszko in The American Revolution (New York, NY: The Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences, 1975)

- Harris, C. Leon, tran., ‘Pension Application of Isaac Grant, S4305’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/S4305.pdf>

- Harris, C. Leon, tran., ‘Pension Application of John Dupuy, W7060’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/W7060.pdf>

- Harris, C. Leon, tran., ‘Pension Application of John O. F. Martin, S30569’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1834) <http://revwarapps.org/S30569.pdf>

- Harris, C. Leon, tran., ‘Pension Application of William Burchett, S1179’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1832) <http://revwarapps.org/S1179.pdf>

- Harris, C. Leon, tran., ‘Pension Application of William Everett, S3342’ (Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements, 1833) <http://revwarapps.org/S3342.pdf>

- Haynes, Kenneth, ‘Questions Concerning the North Carolina Campaign of 1781 and the Race to the Dan in Particular’, 2005, Halifax County (Va.) Historical Society

- Headspeth, W. Carroll, and Spurgeon Compton, A Masterful Maneuver: The Retreat to the Dan (South Boston, Va.: Green’s Printing Shop)

- Holland, Samuel, and Thomas Jeffreys, ‘Jeffery’s 1776 Map of the Most Inhabited Part of Virginia Containing the Whole Province of Maryland with Part of Pennsylvania, New Jersey and North Carolina – Southern Section’ (The American Atlas: Or, A Geographical Description Of The Whole Continent Of America, 1776), Map Geeks <https://mapgeeks.org/wp-content/uploads/1776-Map-of-Virginia-containing-Maryland-Southern-Section.jpg>

- Johnson, William, and Nathanael Greene, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, Major General of the Armies of the United States in the War of the Revolution (Charleston, S.C.: Printed for the author, by A.E. Miller, 1822) <http://archive.org/details/nathanaelgreene01johnrich> [accessed 13 December 2021]

- Kalmanson, Arnold W., ‘Otho Holland Williams and the Southern Campaign of 1780-1782’ (Salisbury University, 1990) <http://mdsoar.org/handle/11603/11437> [accessed 13 May 2020]

- Kirkwood, Robert, and Joseph Brown Turner, The Journal and Order Book of Captain Robert Kirkwood of the Delaware Regiment of the Continental Line (Wilmington, The Historical Society of Delaware, 1910) <http://archive.org/details/journalorderboo00kirk> [accessed 1 February 2022]

- Lee, Henry, The Campaign of 1781 in the Carolinas (Philadelphia, E. Littell, 1824) <http://archive.org/details/campaignincarol00leegoog> [accessed 28 January 2022]

- Lee, Henry, Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States, Second Edition (Washington, D.C.: Peter Force, 1827)

- Lossing, Benson John, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution: Or, Illustrations by Pen and Pencil of the History, Biography, Scenery, Relics and Traditions, of the War for Independence (New York : Harper & Bros., 1851) <http://archive.org/details/pictorialfieldbo02lossuoft> [accessed 25 November 2020]

- MAAR Associates, Inc., and Hill Studio, P.C., ‘Historic Architectural Resources Survey of Halifax County, Virginia’ (Virginia Department of Historic Resources and Halifax County, 2008)

- Morrill, Dan L., Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution (Baltimore, Md.: The Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1993)

- Morris, Lewis, ‘Lewis Morris, Jr., to His Father, General Lewis Morris’, in The Spirit of ’Seventy-Six, ed. by Henry Steele Commager and Robert Morris (New York, NY: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1975)

- O’Kelley, Patrick, Nothing but Blood and Slaughter: The Revolutionary War in the Carolinas, Volume Three, 1781 (Booklocker.com, Inc., 2005)

- Pancake, John S., This Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas, 1780-1782 (University, AL : University of Alabama Press, 1985) <http://archive.org/details/thisdestructivew00panc> [accessed 13 October 2020]

- Perkins, Cary, In-Person Interview, Halifax-South Boston County Library, Local History Room, 2021

- Powell, Douglas, ‘Halifax Gateway Project Material: “Gen. Nathanael Greene North of the Banister River”’, 2016

- Rankin, Hugh F., The North Carolina Continentals (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1971)

- Seymour, William, A Journal of the Southern Expedition, 1780-1783 (The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 1883) <http://archive.org/details/jstor-20084613> [accessed 19 November 2021]

- Sherman, Wm. Thomas, Calendar and Record of the Revolutionary War in the South: 1780-1781, Tenth Edition (Seattle, WA: Gun Jones Publishing, 2007) <https://www.americanrevolution.org/calendar_south_10_ed_update_2017.pdf>

- Showman, Richard K., Dennis M. Conrad, and Roger N. Parks, eds., The Papers of General Nathanael Greene: Vol. VII: 26 December 1780-29 March 1781 (UNC Press Books, 2015)

- Stedman, C., Patrick Byrne, and Patrick Wogan, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War (Dublin: Printed for Messrs. P. Wogan, P. Byrne, J. Moore, and W. Jones, 1794), ii <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100584349> [accessed 31 January 2022]

- Tarleton, Banastre, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America (London : Printed for T. Cadell, 1787) <http://archive.org/details/historyofcampaig00tarl> [accessed 19 September 2020]

- Tuck, Faye Royster, Yesterday—Gone Forever (Halifax, Va.: Halifax County Historical Society, 2004)

Note: All pension applications on the “Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Applications & Rosters” website (revwarapps.org) mentioning Boyd, Irvine, Halifax, and their spelling variants were reviewed. Only those with significant inputs to this page are listed above.

[1] A preacher who traveled North Carolina collecting war stories in the mid-1800s, Rev. E.W. Caruthers (1856), incorrectly reported that Morgan came here, which some later sources repeat. Suffering from sciatica and diarrhea to the point that he traveled much of the way from S.C. lying down in a wagon, Morgan was granted a leave of absence by Greene at Guilford Court House and left for home in Virginia (Graham 1859).

[2] Quoted in Showman et al. 2015.

[3] Tuck.

[4] See the quotation further down the page from James Irvine in his application for a veteran’s pension (1832). Deeds for the brothers’ tracts all say Irvine (Dodson 1998), and the majority of applicants in a large database (revwarapp.org) call it “Irvine’s.”

[5] Claims.

[6] Lee (1824), who quotes a Carrington letter.

[7] Lorance (1832) says he was in the unit; Johnson (1822) says the boats were stored away from the crossing sites.

[8] Lee 1827.

[9] Haimen 1975.

[10] British Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton (1787), who was with O’Hara’s brigade, reports finding “some works evacuated” (though at “Boyd’s”; see Footnote 13). Fuller says he found traces here in the mid-1900s.

[11] Lee and other sources claim the light corps crossed the day after the main army. But both Williams (quoted in Sherman) and Capt. Robert Kirkwood (1910), assigned to the corps, report crossing on the 14th. Lee, writing 40 years later, is known to have gotten his dates and places wrong at times.

[12] Some modern sources claim Lee crossed at Boyd’s, because he was ordered to, and he says in his memoir that he took to road to Boyd’s (Lee 1827). However, from his starting point, the road to Boyd’s was also the road to Irvine’s Ferry. No records indicate Carrington moved from Irvine’s to Boyd’s. Lee does not specify where he actually crossed, but he states his cavalry arrived as the last of Williams’ infantry got across, and Greene and Williams confirm Williams crossed at Irvine’s. This makes sense, given that the cavalry was acting as a rear guard for the infantry. Lee does not mention receiving Greene’s order. Taken together, these points suggest the order never reached the highly mobile cavalry, so Lee continued protecting Williams’ force all the way to Irvine’s.

[13] Caruthers 1856. Tarleton says the British went to Boyd’s. However, Stedman (1794), a commissary officer under Cornwallis, specifies, “The light army, which was the last in crossing, was so closely pursued, that scarcely had its rear landed, when the British advance appeared on the opposite banks…” It is possible Tarleton was sent on to Boyd’s, but no other records support that or indicate earthworks were built at Boyd’s (see Footnote 9). The only record of British damage to property was at Irvine’s (per the James Irvine quote in the next section).

[14] Sherman.

[15] Johnson.

[16] Irvine.

[17] Unless otherwise footnoted, all letters and orders quoted or described on this page were found in Showman.

[18] Tuck.

[19] Headspeth & Compton.

[20] Tuck.

[21] Oldham 1832.

[22] Irvine 1832.

[23] Quoted in Caruthers.

[24] Headspeath and Compton.

[25] Some sources suggest the camp may have been in modern Halifax at a later courthouse built near the current building. A contract for a new building at that site was awarded by the county in 1774. A local history book says court sessions were being held there by August 1777, at what was still called the “new” courthouse into the 1780s (Tuck). None of the records related to the crossing specify “new,” and a deed from 1785 states that court sessions were still being held at the old courthouse in today’s Crystal Hill. Greene mentions in a Feb. 15 letter to Baron Friedrich von Steuben his plans to cross the next river north, the Banister, while supplies will be sent across the Staunton River in case they have to retreat further (Showman). Also, a pension application places the camp at “Halifax old Court House,” stating it was 12 miles from Cole’s Ferry over the Staunton, which is about that distance from here (Adams 1832). Williams (in Showman) and his subordinate Kirkwood (1910) state they crossed the Banister. Their position keeps the light corps between the British and the army only if the army is at Crystal Hill. Other pension applications specify actions that happened at the “old” courthouse throughout the war. Most modern-era accounts from local sources, and most local historians AmRevNC contacted, said the old courthouse was the campsite.

[26] A 1909 deed map (in Cook 1972) places it here when overlaid on a modern road map. A different, somewhat skewed map appears to do so as well. Finally, a 1941 article says the old courthouse was within a few hundred yards of a historically black church, which describes Crystal Hill Baptist Church across the road (quoted in Cook 1972.)

[27] Martin 1833.

[28] To Joseph Clay, Feb. 18 (Showman).

[29] Eanes 2021, based on claims for reimbursement.

[30] Morris.

[31] From James Varnum, Feb. 21 (Showman).

[32] Edmunds Vol. 2.

[33] Tuck.

[a] Al Zimmerman, owner of part of the former James Irvine property, saw the tavern near the southwest corner of US 58 and Old Cool Springs Road before its destruction (interview and tour, 2/17/2022).