Blood at Buchoi

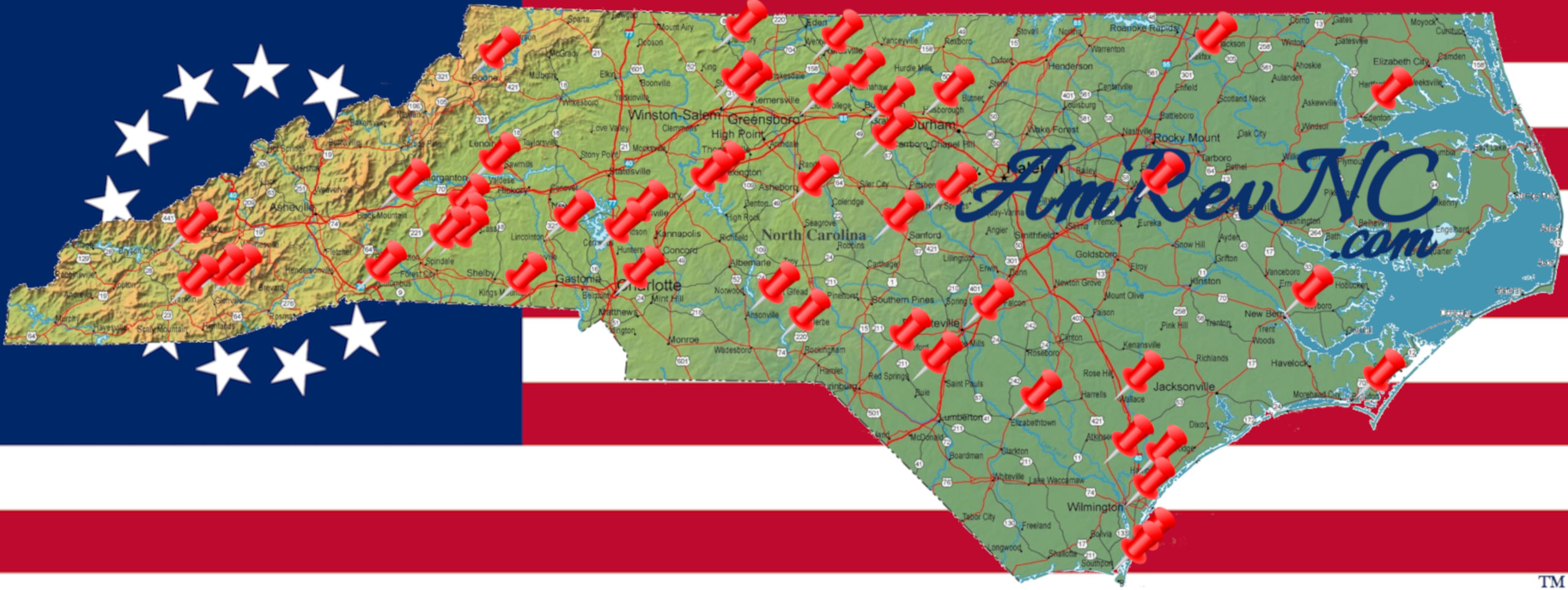

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 34.2214, -77.9827.

Type: Sight

Tour: Cape Fear

County: Brunswick

![]() Full

Full

Park in the lot near the entrance of the Brunswick Riverwalk off NC 133.

This tour visits a grassy area and sandy trail that are relatively flat, and the latter is wheelchair accessible. Some people with mobility issues may need assistance, however. You can also just remain in your vehicle.

Context

A British corps of 300 under Maj. James Craig occupied Wilmington in January 1781.

A British corps of 300 under Maj. James Craig occupied Wilmington in January 1781.

Situation

Loyalist

Loyalist or “Tory” supporters of the king formed militia companies of part-time soldiers to regain control of Southeastern North Carolina for the British and gather supplies for Craig’s force.

Patriot

In October, North Carolina sent Brig. Gen. Griffith Rutherford and 1,000 men or more from the western part of the state to suppress the Loyalists and remove Craig. The main force moved around to the north, ending up at Heron’s Bridge nine miles above town. Maj. Joseph Graham’s unit was one of several detached under Col. Robert Smith to approach Wilmington directly from the west.

Date

Wednesday, November 14, 1781.

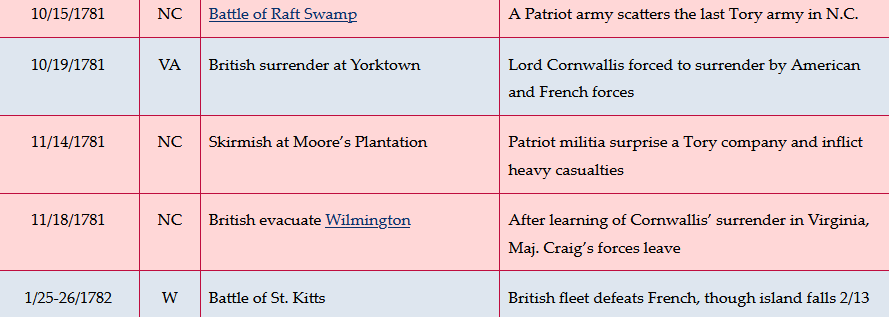

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

Buchoi

Walk toward the playground and turn right inside the rail fence. Continue toward the road and stop somewhere between the playground and the driveway.

You are standing on Buchoi Plantation, owned by Alfred Moore during the American Revolution. A 1970s archaeology study found “a house structure, including ballast stone foundations, brick rubble, and a brick cistern” about 200 feet east of the highway. The plantation had “a separate kitchen building… a barn, slave quarters, and other outbuildings.”1

You are standing on Buchoi Plantation, owned by Alfred Moore during the American Revolution. A 1970s archaeology study found “a house structure, including ballast stone foundations, brick rubble, and a brick cistern” about 200 feet east of the highway. The plantation had “a separate kitchen building… a barn, slave quarters, and other outbuildings.”1

A sign you’ll see later suggests the main house was in this area, but a 2016 archaeology dig found no structures.2 Given the 200-foot measure, and that plantation homes normally were built at the highest point of the property, it may have been at the top of this rise near the modern stage. Some outbuilding remains may be under the parking lot.

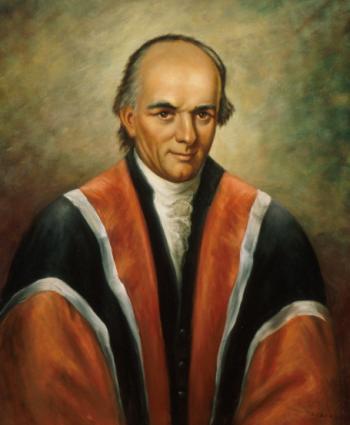

Alfred Moore

The Moore family was a dominant force in this area, as farm-owners, lawyers, and merchants of both goods and enslaved people. Alfred’s great-grandfather founded colonial capital Brunswick Town a dozen miles down the road, and Alfred was raised there. His father Maurice, a judge, sent him to school in Boston at age nine, and then trained him to be a lawyer after he returned.3

The Moore family was a dominant force in this area, as farm-owners, lawyers, and merchants of both goods and enslaved people. Alfred’s great-grandfather founded colonial capital Brunswick Town a dozen miles down the road, and Alfred was raised there. His father Maurice, a judge, sent him to school in Boston at age nine, and then trained him to be a lawyer after he returned.3

Moore may have received military training from a British officer while in Boston, but chose not to become one. His first combat experience came in 1771 around age 16, under Royal Gov. William Tryon against armed protesters called the “Regulators.” Five years later, at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge, he helped defeat Loyalists trying to join Tryon’s replacement at Fort Johnston in today’s Southport. He was at the fort when a British fleet left the area, was named a captain in the Continental Army,4 and helped defend Charleston from the fleet. He resigned the next year to be closer to home, after his father and brother died of illness, but remained active as a colonel in the Patriot militia. It’s unclear when or how he obtained “Buchoi”—or why it was named that!5 The number of people he held here in slavery also is unknown.

As the war wound down in 1782, Moore turned to politics, becoming a state senator and then attorney general. A few years later he moved to a plantation outside of Hillsborough. He was on the first board of trustees for the University of North Carolina, and helped select the Chapel Hill site.

Moore was described as “five feet four inches in height, neat in dress, graceful in manner, but frail in body.”6 He became a judge in 1798, and two years later he replaced another North Carolinian on the U.S. Supreme Court, James Iredell. But he only served four years and died at 55. You can visit his grave at Brunswick Town. Moore County, created while he was alive, and Moore’s Square in Raleigh are named for him.

A Whig Surprise Arrives

Go to the opposite side of the lot from the playground and take the trail closest to the road. Walk a short distance into the woods, and turn right at the sign saying “Nature Trail.” Stop at the foundation ruins on the right.

The plantation buildings here were probably built after the Revolution.7 Perhaps they were part of the farm operation, or they may have been later additions related to a grain mill in the area during the war. It was probably on the small stream at the bottom of the ravine behind you.8

The plantation buildings here were probably built after the Revolution.7 Perhaps they were part of the farm operation, or they may have been later additions related to a grain mill in the area during the war. It was probably on the small stream at the bottom of the ravine behind you.8

Pension applications from several veterans confirm a skirmish happened here, but most of the story comes from a single source, the Patriot commander. Believe details with caution!

Early on Wednesday, November 14, 1781, Smith’s detachment is moving toward Wilmington roughly where US 74/76 runs now. Graham commands troops marching a few hundred yards ahead. Capturing some Loyalists, the Patriots learn of 50 British soldiers in a fortified brick house near the ferry over today’s Brunswick River. The house was in modern Leland, around where NC 133 leaves 74/76. After arriving there and capturing soldiers seeking firewood, they learn 100 Tories have camped here at Moore’s Plantation. Smith sends Graham to attack them.

Look toward NC 133.

Graham’s troops include cavalry trained and equipped to fight from horseback, and foot soldiers using their horses for transportation. They ride down the sandy wagon road to Wilmington where NC 133 is now. When close enough to see campfire smoke and hear the Tory horses, the infantry dismounts and spreads into a line with the cavalry “dragoons” behind. All begin moving this way, still on the far side of the ravine.

By a double coincidence, the Tory commander is a Col. Graham, unrelated to the major, and at that moment he is heading for the brick house. Militia soldiers do not wear uniforms. So when he first sees the Patriots (or “Whigs”) somewhere up the road, he continues toward them, assuming they are Loyalists. Only when he gets within 60 yards does he realize his mistake! He spins his horse and races back this way. “With much difficulty the infantry were restrained from firing at him,” Maj. Graham writes; he probably wants to maintain the surprise as long as possible. He orders his foot soldiers to run forward in their line.

He continues, “A causeway being opposite the house, and an enclosure of some low grounds, the infantry came up at a trot and deployed along a fence, about one hundred and forty yards from the enemy, and resting their guns on the fence fired as they came into place.”9 The causeway is probably a raised mound of timber and sand carrying the road across the low area downhill. The distance suggests the fence is somewhere near this spot, perhaps built to prevent livestock from falling into the ravine.10 One Whig says a sentinel on the Tory side of the fence, apparently not seeing Col. Graham pass by, cries “very often ‘who are you’” until the Patriots open fire.11

Tories are Scattered

Walk back toward the parking lot until you see part of the river in the distance.

Col. Graham’s Loyalists are still trying to form a line somewhere in front of you, but a few manage to return fire. Maj. Graham says, “When our fire commenced, they began to break, and… none were attempting to avail themselves of the defence or shelter of the buildings. The dragoons were ordered to charge them, which was done at full speed.” The horsemen fly down the road past you wielding swords. The Tories scatter, some on horseback. Most take off to your left toward salt marshes that line the river, narrower at that time. Graham writes, “many of them got (only) one slight cut with the sabre, quit their horses, and escaped; but several were shot with pistols in the marsh.” The Loyalist commander and a couple officers take off down the road. Patriots try to follow, but the Tories’ horses are too fast.

Col. Graham’s Loyalists are still trying to form a line somewhere in front of you, but a few manage to return fire. Maj. Graham says, “When our fire commenced, they began to break, and… none were attempting to avail themselves of the defence or shelter of the buildings. The dragoons were ordered to charge them, which was done at full speed.” The horsemen fly down the road past you wielding swords. The Tories scatter, some on horseback. Most take off to your left toward salt marshes that line the river, narrower at that time. Graham writes, “many of them got (only) one slight cut with the sabre, quit their horses, and escaped; but several were shot with pistols in the marsh.” The Loyalist commander and a couple officers take off down the road. Patriots try to follow, but the Tories’ horses are too fast.

Forty percent of the Loyalists are killed or wounded. Reports differ as to whether the others escape, or some are taken prisoner. No Patriots are harmed.

“After collecting the arms, horses and spoils of the enemy’s camp,” Maj. Graham says, his force returns to the Patriots near the brick house. There they learn sounds of the skirmish reached Wilmington, because the militia near the house heard drums beating out orders in town.

An attack a couple days later on the heavily fortified brick house failed. Graham’s force passed down the road again soon after, on a scouting foray to Brunswick Town and Fort Johnston.

Battle Map

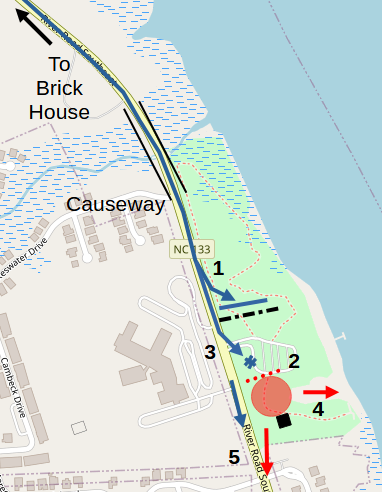

Skirmish at Moore’s Plantation: All locations are approximate. 1) After a chance meeting with the Loyalist commander, Patriot militia cross causeway, line fence, fire volley. 2) Loyalists try to form line and return fire. 3) Patriot cavalry charges. 4) Loyalists scatter into marshes. 5) Their officers escape down road.

Casualties

- Loyalist: 12 killed, 30 wounded, unknown captured.

- Patriots: 0.

Historical Tidbit

The “brick house” provides a lesson on the detective work involved in history writing. Veterans’ statements said the brick house “covered” the Wilmington ferry, so many historians assumed it was across the Cape Fear River from there, perhaps at today’s parking lot for the U.S.S. North Carolina. However, all but one of the half-dozen accounts from veterans, including Graham’s, place it 1.5 to two miles west of Wilmington (and the one says a mile). This puts it close to or in Leland. One says it was “on” the river, meaning the Cape Fear, but today’s Brunswick River was considered a branch of the Cape Fear at the time.12 Also, Graham refers to the plantation being a mile south of the brick house, matching the distance and direction to here from Leland. You are two miles west-southwest of the battleship.

A local historian reports a ballast-stone causeway ran across Eagle’s Island, the one between the rivers, but mentions no other structure on the then-swampy island.13

Also, it was not unusual for a combination of two nearby ferry crossings connected by a direct route to be called “the” ferry, as at Colson’s Ferry across the Yadkin and Rocky rivers east of Charlotte. A single toll was charged for the two crossings from Wilmington.14 Taken together, these facts point to the brick house being in Leland.

More Information

- ‘Alfred Moore’, Oyez <https://www.oyez.org/justices/alfred_moore> [accessed 30 November 2024]

- ‘Alfred Moore (1755-1810)’, WikiTree FREE Family Tree <https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Moore-17802> [accessed 3 December 2024]

- ‘Anthropology Students Search for Old Rice Plantation’, University of North Carolina Wilmington (Archive-It), 2016 <https://wayback.archive-it.org/18777/20220510111459/https://uncw.edu/news/2016/06/anthropology-students-search-for-old-rice-plantation.html> [accessed 23 January 2025]

- Cameron, Rebecca, Christmas at Buchoi, a North Carolina Rice Plantation, North Carolina Booklet ; (North Carolina Society, Daughters of the American Revolution, 1913)

- Davis, Junius, ‘Alfred Moore and James Iredell: Revolutionary Patriots, and Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States’ (North Carolina Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 1899), North Carolina Room, New Hanover County Public Library, Vertical Files

- Dunkerly, Robert M., Redcoats on the River: Southeastern North Carolina in the Revolutionary War, 1st ed. (Dram Tree Books, 2008)

- Graham, William A., General Joseph Graham and His Papers on North Carolina Revolutionary History (Edwards & Broughton, 1904) <http://archive.org/details/cu31924032738233>.

- Graves, Will, ‘Pension Application of George Hillen, S7006’, Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters, 1834 <https://revwarapps.org/s7006.pdf> [accessed 23 November 2024]

- Graves, Will, ‘Pension Application of James Jones, S31170’, Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters, 1833 <https://revwarapps.org/s31170.pdf> [accessed 23 November 2024]

- Graves, Will, ‘Pension Application of John Espy (Espey), S31669’, Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters, 1832 <https://revwarapps.org/s31669.pdf> [accessed 23 November 2024]

- ‘History’, Moorefields <https://moorefields.org/history> [accessed 30 November 2024]

- ‘Judge Alfred Moore of the Supreme Court of the U.S.’, North Carolina Room, New Hanover County Public Library, Vertical Files

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Moore’s Plantation’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2012 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_moores_plantation.html> [accessed 23 November 2024]

- Long, Jim, tran., ‘Pension Application of Lewis Atkins, S2929’, Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters, 1833

- ‘Marker: D-25’ <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=D-25> [accessed 26 May 2022]

- ‘Moore, Alfred’, NCpedia <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/moore-alfred> [accessed 26 May 2022]

- ‘Previous Associate Justices: Alfred Moore, 1800-1804’, Supreme Court Historical Society <https://supremecourthistory.org/associate-justices/alfred-moore-1800-1804/> [accessed 30 November 2024]

- Reaves, Bill, Notes on the Brunswick River and Its Environs (1988), North Carolina Room, New Hanover County Public Library, Vertical Files, ‘Brunswick River’

- Reaves, Bill, Southport (Smithville): A Chronology, Vol. I (1520-1887), Southport Historical Society, 1992

- Reilly, Terry, ‘UNCW Team Leads Brunswick Plantation Archaeological Expedition’, Star – News (20 May 2015) <https://www.proquest.com/docview/1682249743/abstract/6AC815B029824166PQ/1> [accessed 11 December 2024]

- ‘The Town Of Belville’s Past, Present & Future’, Life In Brunswick County, 2017 <https://lifeinbrunswickcounty.com/the-town-of-belvilles-past-present-future/> [accessed 26 May 2022]

- ‘There Is History Buried in Belville’s Riverwalk Park’, Port City Daily, 2023 <https://portcitydaily.com/local-news/2023/03/05/there-is-history-buried-in-belvilles-riverwalk-park/> [accessed 23 November 2024]

- ‘UNCW Archaeological Field School in the Wilmington Area, Summer Session I 2016, UNC Wilmington’, UNCW <http://people.uncw.edu/rebere/fieldschool2016.htm> [accessed 26 May 2022]

- Wagner, Adam, ‘UNCW Will Dig for Old Plantation at Riverwalk Site’, Wilmington Star-News <https://www.starnewsonline.com/story/news/2016/02/05/uncw-will-dig-for-old-plantation-at-brunswick-riverwalk-site/30992476007/> [accessed 26 May 2022]

- Zimmerman, Susan K, and R Neil Vance, trans., ‘Pension Application of Josiah (Josias) Martin, Mary Martin, W1047’, Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters, 1832 <https://revwarapps.org/w1047.pdf>

1 “UNCW Archaeological Field Site…”

2 Ibid., and Wagner 2016.

3 “Moore, Alfred.”

4 Reaves 1992.

5 One source says the plantation was his father’s (“Judge Alfred Moore of the Supreme Court of the U.S.”), but none AmRevNC found explained the name. Web searches and translation services turned up no definition for the word in any language.

6 Davis 1899.

7 Reilly 2015.

8 Two veterans of the skirmish here refer to the mill, one calling it “Grayar’s.”

9 Graham.

10 Graham’s account is unclear on the fence location. A strict reading implies it was on the far side of the causeway and ravine. However, the distance at which they were high enough to see the Loyalists from the north side was far out of range for all but the very best marksmen and rifles of the day (assuming the landform was similar to today’s). So he must have meant the men crossed the causeway to line the fence.

11 “Pension Application of Josiah (Josias) Martin.”

12 Reaves 1988.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

← Brunswick Town | Cape Fear Tour | Wilmington →