A General Dies with His Troops

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 36.0399, -77.4134.

Type: Stop

Tour: Rebellion

County: Halifax

![]() Full

Full

If you approach the coordinates from Hopgood, to the south on NC 125, you will find a wide shoulder just north of the state highway marker for James Hogun. Most vehicles will also fit on the southbound shoulder before reaching the marker on the other side.

Description

If dedication to one’s soldiers is the mark of a great leader, James Hogun was the ultimate leader. When or why Hogun moved from Ireland to the colonies is unknown, but he married in Halifax County in October 1751. For reasons explained below, nothing is known of his activities from then until the war. But he must have become a successful landowner, because that was true of everyone elected to the N.C. Provincial Congress in 1774. This gathering of representatives from across the colony first challenged the royal governor, and then became the first colonial congress to endorse independence in April 1776, in Halifax.

If dedication to one’s soldiers is the mark of a great leader, James Hogun was the ultimate leader. When or why Hogun moved from Ireland to the colonies is unknown, but he married in Halifax County in October 1751. For reasons explained below, nothing is known of his activities from then until the war. But he must have become a successful landowner, because that was true of everyone elected to the N.C. Provincial Congress in 1774. This gathering of representatives from across the colony first challenged the royal governor, and then became the first colonial congress to endorse independence in April 1776, in Halifax.

Hogun helped form the Halifax County part-time defense force (“militia”) for the new state. Then in November 1776, he became a colonel in the regular Continental Army, commanding the N.C. Seventh Regiment. The regiment fought under Gen. George Washington at battles including Brandywine and Germantown (Penn.), and was in the famous winter camp at Valley Forge. Hogun was described as leading with “‘distinguished intrepidity.’”[1]

He was sent back to North Carolina to recruit a new regiment, which he then took north in 1778 to build defenses at West Point, N.Y., where the famous military academy is now. On the way, they stopped in Carlisle, Penn., to get the new smallpox vaccine.[a]

Starting in January 1779, the regiment served guard duty in Philadelphia under Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold, the same month Hogun was named a brigadier general by the Continental Congress. The state assembly recommended someone else, but N.C. Congressman Thomas Burke pushed Hogun as a reward for his conduct in battle. Hogun took over command of Philadelphia from Arnold, 18 months before Arnold turned traitor. When draftees finished their enlistments the next month, he reported to Gen. Washington he had only 165 men to cover 82 guard posts, barely allowing one change of guard each day![2]

Hogun remained in that role until ordered with the N.C. brigade to Charleston in August. Interrupted by a long pause at the army’s winter camp in Morristown, N.J., as events unfolded to the south, plus a difficult march, they did not arrive until March.[3] On the way he wrote Washington from Wilmington of “the many Obsticles [sic] that has tended to the Impeding my March to the Southward.” But he lists no complaints.

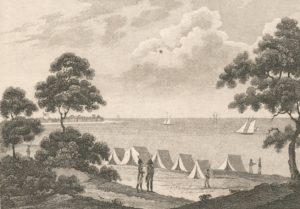

Captured when the Continental forces at Charleston were forced to surrender in May 1780, Hogun chose to suffer along with his men at the Haddrel’s Point (S.C.) prison camp rather than accept a parole to live with other officers in Charleston. He had slightly better living conditions, in one of a set of three barracks with other officers. The soldiers were lucky if they had tents. Hogun also stayed to keep them from taking British offers of freedom and money to switch sides, with the agreement they would fight in the West Indies, not the U.S. (Up to 500 Americans may have accepted.)[4]

Hogun’s decision proved fatal: He died of natural causes on Thursday, January 4, 1781. He was not alone in his fate. Of 1,800 North Carolinians interned there, 1,100 died.[5] Hogun was buried among his men, and his grave is lost to history.

What to See

Look at the state historical marker, and trace a line with your eyes about 60 yards behind it—a little over half an American football field.

Hogun’s house was toward the back of the modern farm field, near the small stream running behind the trees you see today. In 1775 at least four enslaved people—Ceaser (sic), Sam, Hannah, “and old Bridge”—lived here as well. Control of them was passed to his wife Ruth during her lifetime and then his only son Lemuel, according to his will.[6]

The house was still standing during the Civil War in the 1860s, though owned by another family. Union troops reportedly confiscated or destroyed Hogun’s papers here, which is why so little is known today about one of only five North Carolina generals in the Continental Army.[7]

More Information

- Borick, Carl P., Relieve Us of This Burthen: American Prisoners of War in the Revolutionary South, 1780-1782 (University of South Carolina Press, 2012)

- Clark, Walter, ‘General James Hogun: A Fragment of a Lost Chapter’, The North Carolina Teacher, 1892 <http://archive.org/details/northcarolinatea1892rale> [accessed 17 April 2020]

- Dacus, Jeff, ‘Unknown and Forgotten: James Hogun’, Journal of the American Revolution, 2017 <https://allthingsliberty.com/2017/09/unknown-forgotten-james-hogun/> [accessed 21 September 2020]

- ‘Geni – Brig. Gen. James Hogun (b. – 1781)- Mount Pleasant’, GENi <https://www.geni.com/people/Brig-Gen-James-Hogun/6000000071967417456#name=Brig.%20Gen.%20James%20Hogun?> [accessed 21 September 2020]

- Hogun, James, ‘To George Washington from Brigadier General James Hogun, 3 Apr …’, Founders Online, 1779 <http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-19-02-0680> [accessed 21 September 2020]

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Colonels’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2012 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/nc_patriot_military_colonels.html> [accessed 21 September 2020]

- Rankin, Hugh F., The North Carolina Continentals (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1971)

- Rankin, Hugh F., ‘Hogun, James’, NCpedia, 1988 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/hogun-james> [accessed 21 September 2020]

- Rankin, Hugh F., The North Carolina Continentals (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1971)

- Russell, Phillips, North Carolina in the Revolutionary War (Charlotte, N.C.: Heritage Printers, Inc., 1965)

- Sherman, Wm. Thomas, Calendar and Record of the Revolutionary War in the South: 1780-1781, Tenth Edition (Seattle, WA: Gun Jones Publishing, 2007) <https://www.americanrevolution.org/calendar_south_10_ed_update_2017.pdf>

[1] Rankin 1988.

[2] Hogun 1779.

[3] Dacus.

[4] British offer: Rankin 1971; barracks: Borick 2012.

[5] Clark 1892.

[6] GENi.

[7] Ibid.

[a] Rankin 1971.

← W. Blount Birthsite | Rebellion Tour | Gourd Patch Affair →