A Former Capital Burns

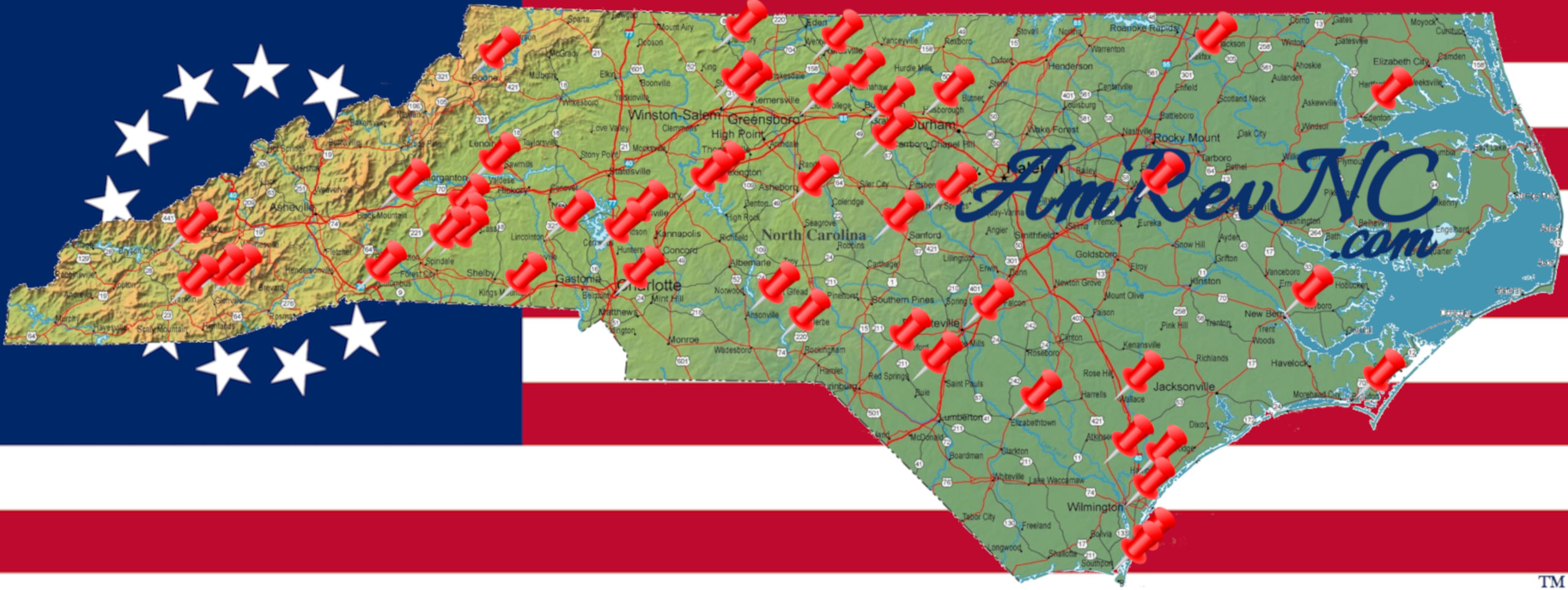

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 34.0412, -77.9484.

Type: Sight

Tour: Cape Fear

County: Brunswick

![]() Full

Full

What once was a vibrant colonial capital was turned into a Confederate fort during the Civil War, so you will park at Brunswick Town & Fort Anderson State Historic Site. The site can only be toured when the Visitor Center is open, so check their website for their hours when planning your trip. For more of the site’s fascinating history and artifacts, tour the center. Then use this page to add Revolutionary War details as you walk the paved trails.

Context

Brunswick Town was officially founded in 1726, became the N.C. capital when the colonial governor moved here, and remained an important port at the start of the American Revolution.

Brunswick Town was officially founded in 1726, became the N.C. capital when the colonial governor moved here, and remained an important port at the start of the American Revolution.

Situations

British/Tory

Months before the Declaration of Independence in 1776, a British army was stuck on ships off the mouth of the Cape Fear River. Needing supplies, the British landed foraging parties, but were constantly harassed by local Patriots (“Whigs”). After a British ship cruising the river was fired upon by snipers yet again, the British decided to take stronger action.

Continental/Patriot

Patriot part-time soldiers called “militia” have burned Fort Johnston in today’s Southport and fortified Wilmington upriver. They also are scattered about the area, resisting foragers and taking potshots at passing British ships whenever they can.

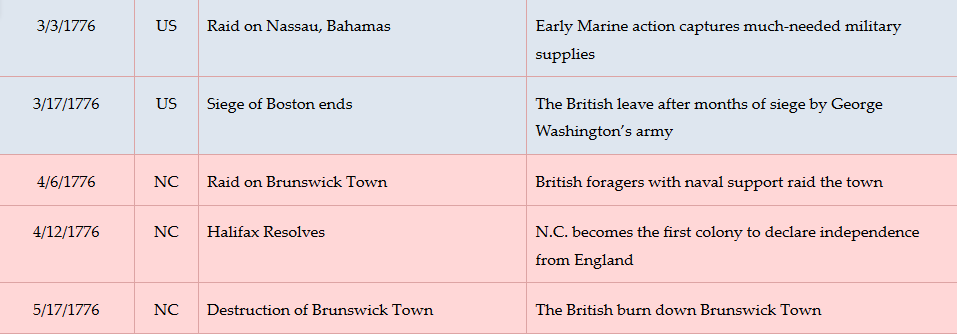

Dates

Monday, February 19, 1766–Friday, May 17, 1776.

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

Provincial Prominence

Take the south exit from the Visitors Center (not the front door), and follow the trail through the Civil War earthworks nearly to the river. Just before the T-intersection there, stop at the sign for the Judge Maurice Moore house on the right.

Starting in 1725, Brunswick Town “became a center of commerce—with tobacco, lumber, naval stores, furs, and other products being shipped out—as well as the home of a number of prominent persons.”1 Among the “prominent persons” were royal governors Arthur Dobbs and William Tryon, making this the de facto capital of the Province of North Carolina from Dobb’s arrival in 1754 until Tryon moved to his new palace in New Bern in 1770.

Starting in 1725, Brunswick Town “became a center of commerce—with tobacco, lumber, naval stores, furs, and other products being shipped out—as well as the home of a number of prominent persons.”1 Among the “prominent persons” were royal governors Arthur Dobbs and William Tryon, making this the de facto capital of the Province of North Carolina from Dobb’s arrival in 1754 until Tryon moved to his new palace in New Bern in 1770.

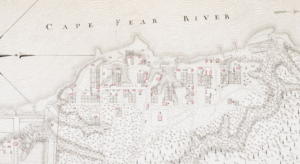

By the American Revolution, there are at least 120 buildings2 including 50 or 60 houses here. Many are two stories tall and built out of ballast stones from ships, which had been used to balance out loads.3 However, the town has been eclipsed by New Bern and Wilmington, so its population is down to merchant workers and only a few families.

Look at the Moore lot.

Maurice Moore, son of the town’s founder, “King” Maurice, was given this half-acre lot in 1759. In time he had a house built here in the West Indies style, with a porch across the front, where he lived with his wife Anne. He joined the colonial legislature around age 22, and six years later he was appointed an appeals court judge in Salisbury. He was suspended briefly after writing against the Stamp Act, discussed below.

Moore commanded the cavalry in the colonial army sent to repress western protesters against Tryon’s government for corruption and unfair taxation, called the “Regulators.” He was a judge in two Hillsborough trials of Regulators, sentencing some to hang in 1771 after the Battle of Alamance. But he argued for Tryon to go easy on the rest.

As wider rebellion broke out, Moore argued for a slow approach to the differences with the King and Parliament, but served in the rebels’ Third Provincial Congress. He died in early 1777, though exactly where, when, and how are unknown.

An archaeologist wrote, a “burned pine floor in the cellar suggested that this house burned.” An unusual smokehouse, with an external fire pit and brick tunnel to carry the smoke into the structure, was only a few years old when it and the house were burned down.4

Turn right, and take the sidewalk to the end, by the fenced area around a series of room foundations.

Goods and people from around the world arrived at the town’s four docks, two of which were somewhere just south of here. Sadly, some of those people were enslaved, brought here to be sold.5 In this lot archaeologists found a pocketknife with Malaysian writing on it, and china from China was discovered in every house in town!

During the Revolution, a former pub (and at some point tailor shop) stands here. You and it are surrounded by a low ballast-stone wall running 70 feet left to right and 18 feet wide. Part of the wall, a semicircle on the riverside end, is still visible downhill. Inside are six rooms, each 10 feet wide, with a shared chimney between each pair.

Some problems are universal, including drunken sailors. The law the Colonial Assembly passed in 1745 to encourage settlement here said pubs had to stop serving sailors after six hours, and no later than 9 at night in the summer unless their captain approved—in writing!6

British Bullets Fly

Go back to the trail intersection and look out at the river. The island you see did not exist at the time.

As you stand here on Saturday, April 6, 1776, be ready to duck behind a nearby building! A British foraging party captured a Patriot militia officer and five of his men near town after a brief skirmish. British ships are cruising up and down the river firing cannons at anyone not wearing the red jacket of the British infantry.

A British fleet is anchored off the mouth of the Cape Fear near modern Southport, with a British army and the current royal governor on board. In charge of one corps is a man who will become more famous in the state five years later, Brig. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis. On Friday, May 17, his force of 900 Redcoats approach Brunswick Town, probably along the river from the south (to the right). They had been rowed to a landing downriver overnight. You hear shots from sentinels, which are returned by the British, and the Patriots melt into the woods unscathed. The small garrison left here figures out what is happening and escapes town.

Moments later the troops arrive to a huge surprise: The last residents of town are already gone. Part of the force continues to the north past today’s Orton Pond—the last reservoir you passed driving in—hoping to capture an artillery battery there. But it, too, had retired. An historian notes, “All that Lord Cornwallis could obtain for his efforts were twenty bullocks (bulls) and six horses.”7

Most modern sources report that the British burned the southern half of town, where you are standing.8 However, evidence uncovered by the manager of the state historic site indicates the town was burned sometime after 1776, perhaps by British troops occupying Wilmington in 1781.9

Dry’s Dock

Take the trail up the river. Pass the Civil War earthworks. Just beyond the end of the boardwalk railing, stop and look toward the river.

The wharf of William Dry, introduced later, extends into the river from around here in 1776. Wooden timbers from the substructure are still there, and ballast stones are sometimes visible at low tide.10 Smaller ships that could sail to other ports along the Atlantic Coast could dock here. Larger ships had to anchor roughly 50 yards offshore, visitor Alexander Schaw reported, so people and goods were transferred by small boats. The largest could not get past a sand bar in the river named “the Flats” created by silt from Town Creek, which you crossed four miles north of here if you drove from Wilmington.11 Goods for there had to be transferred to smaller boats here.

The wharf of William Dry, introduced later, extends into the river from around here in 1776. Wooden timbers from the substructure are still there, and ballast stones are sometimes visible at low tide.10 Smaller ships that could sail to other ports along the Atlantic Coast could dock here. Larger ships had to anchor roughly 50 yards offshore, visitor Alexander Schaw reported, so people and goods were transferred by small boats. The largest could not get past a sand bar in the river named “the Flats” created by silt from Town Creek, which you crossed four miles north of here if you drove from Wilmington.11 Goods for there had to be transferred to smaller boats here.

In colonial days Brunswick was the biggest supplier to the British Empire worldwide of materials needed for ships, like masts and turpentine (“naval stores”), providing a third of those shipped from America in 1772. That year 142 ships leave from here (and 147 check in). Also flowing out from wharves like Dry’s were furs, tobacco, corn, and rice.12

Patriot Merchants and a Scottish Visitor

Keep going on the trail. Around where it turns away from the river, the northernmost wharf stood.

Continue past the end of the boardwalk onto the paved trail. Go off-trail to the foundation to the right, the Richard Quince House.

English immigrant Richard Quince was a leading merchant in town beginning around 1740. He also served in local political and church offices. Quince was a major exporter of naval stores and other items, and an importer of goods including rum and sugar, using several ships he owned. He and Dry bought Orton Plantation in the 1750s. At one point he held 155 people in slavery, most probably at Orton. By 1769 he was living there and likely used this as his “townhome.” He bought out Dry’s interest in Orton the next year.

English immigrant Richard Quince was a leading merchant in town beginning around 1740. He also served in local political and church offices. Quince was a major exporter of naval stores and other items, and an importer of goods including rum and sugar, using several ships he owned. He and Dry bought Orton Plantation in the 1750s. At one point he held 155 people in slavery, most probably at Orton. By 1769 he was living there and likely used this as his “townhome.” He bought out Dry’s interest in Orton the next year.

After the British imposed a tax on some goods, Boston blocked the import and export of various items, and other colonies joined in. The Cape Fear Sons of Liberty praised Quince in 1770 for supporting the ban despite being a merchant. He chaired the Brunswick Committee of Safety formed to run the town as the colonial government broke down.13

On Tuesday, February 14, 1775, Quince is here, perhaps due to the arrival of his ship, the Rebecca. On it is Schaw’s sister Janet Schaw of Scotland, now noted for her snarky journal of this trip. She was directed to this house. “We got safe on shore,” she wrote, “and tho’ quite dark landed from the boat with little trouble, and proceeded thro’ rows of tar and pitch (awaiting export) to the house of a (merchant), to whom we had been recommended. He received us in a hall which (while) not very orderly, had a cheerful look, to which a large… stove filled with Scotch coals contributed not a little. The night was bitterly cold, and the Master of the house gave us a hospitable welcome.” Her party stayed here for a few days before heading to Wilmington. She described Brunswick as “very poor—a few scattered houses on the edge of the woods, without (paved) street or regularity.”14

It’s unknown where Quince was during the British raids, but he died two years later.15 His house never burned.

Go back to the sidewalk and continue along the earthworks to the marker saying “The Big Guns at Fort Anderson.”

The family of William Dry III moved to Brunswick Town in 1735 when he was in his mid-teens. His mother was Judge Moore’s sister. His dad bought several lots in town, became a merchant, and served as a militia leader and justice of the peace, which included county government duties in those days. Eventually his son inherited those roles, in effect. His home was here, at about the level of the Civil War gun platform. (The platform is at the town’s ground level, as you can see by looking behind you.) Items found in the next gun placement along the sidewalk suggests his wife’s garden was there.16

Wax “bottle seals” with Dry’s name pressed into them, used as stoppers, were found in various places around town by archaeologists. Dry became colonel of the local militia six years after leading the defense against a 1748 raid by the Spanish described under “Historical Tidbits,” and was named the tax collector for the port.17 Dry held at least 130 people in slavery, most probably working in Orton’s rice fields or gathering naval stores. He also had the first ferries from Wilmington built, and a causeway connecting them across Eagle Island.18

Continue up the trail to the enclosure with reproduction stocks in it.

The town’s second courthouse was a few years old when a hurricane knocked it out of commission. However, its shell is apparently still here during the Revolution, because a button from the British Army’s 82nd Regiment was found in the yard. That unit occupied Wilmington for most of 1781, raided throughout the region, and thus may have come to Brunswick and burned it per Footnote 9. A 1775 Irish coin was found here, too.

A Mystery at Church

Head back toward the parking lot, and stop at the building remains on the left nearest the lot.

The 1768 St. Philips Church was the largest in the colony when built, one source says.19 The walls were originally 24 feet high, and part of the floor was paved in the shape of a cross, using brick tiles.20 Royal Gov. Dobbs had promised donations of a pulpit and other items, but died before the building was finished. He was buried in the floor at the near end, by the altar, one of 12 burials archaeologists found there. With no preacher in the region, a judge presided over his funeral. The new governor, William Tryon, donated 11 glass windows. A baby among the altar graves might have been Tryon’s son.21

The 1768 St. Philips Church was the largest in the colony when built, one source says.19 The walls were originally 24 feet high, and part of the floor was paved in the shape of a cross, using brick tiles.20 Royal Gov. Dobbs had promised donations of a pulpit and other items, but died before the building was finished. He was buried in the floor at the near end, by the altar, one of 12 burials archaeologists found there. With no preacher in the region, a judge presided over his funeral. The new governor, William Tryon, donated 11 glass windows. A baby among the altar graves might have been Tryon’s son.21

The British have long been blamed for burning the church, but it was part of the official (Anglican) Church of England. A more likely culprit has emerged. The local Patriot militia destroyed the home and personal property of John Collet, Loyalist commandant of Fort Johnston, the year before. Swiss, and not Anglican22, Collet took advantage of the outbreak of war to lead a Tory force here in March 1776, probably burning both the church and a later stop out of revenge.23

Look at the marker by the cemetery and locate the grave of Benjamin Smith.

Benjamin Smith was born around 1757 to Sarah Moore, the daughter of the owner of Orton Plantation, and a South Carolina planter. He studied in his hometown of Charleston, in Philadelphia, and briefly in London before returning home due to the Revolution. After briefly serving in the S.C. militia, he joined the Continental Army and was an aide to Gen. George Washington in the 1776 Battle of Long Island (N.Y.). The next year he married Sarah Dry, Williams’ daughter. He helped defeat the British two years later at Beaufort, S.C., eventually rising to colonel. He was contracted to rebuild Fort Johnston after the war, and in time was promoted to militia major general.

In 1782 as the war wrapped up, he was elected to the N.C. Senate, and later served in the state house and the state conventions to consider the federal Constitution. He was the Grand Master of the N.C. Masons, and state governor for one year.

He returned to a life of wealth at Orton and other properties, but it did not last. Smith was apparently too generous. In 1792 he donated the land adjacent to Fort Johnston that became “Smithville” in his honor, now Southport. He gave 20,000 acres granted him for his war service to the University of North Carolina, whose board he was on. He and Sarah helped the poor and made the critical mistake of co-signing a loan for a friend, who defaulted, leaving them poor. Smith died a nearly bankrupt widower at his worn-down Smithville home in 1826.

Look into the cemetery for what appears to be a tomb (possibly just a “table marker” above a normal grave). Walk past it parallel to the church wall and find the grave of Alfred Moore, son of Judge Maurice Moore, which has a small Patriot marker at its foot. He served as a Patriot soldier in the Revolution and later was a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Look into the distance beyond the church.

As you stand here on Monday, March 18, 1765, you likely hear the sounds of gunshots. Capt. Alexander Simpson and Lt. Thomas Whitehurst of the Royal Navy gunship Viper apparently both fell in love with Anne Pierson of Norfolk. Simpson married her. No one knows exactly why, but Simpson challenged Whitehurst to a duel. Whitehurst has “his thigh broke(n) by a pistol shot, and his head wounded in several places by the butt end of a horse pistol, of which the pan was broke(n) by the violence of the blows he received on the head from Mr. Simpson,” Gov. Tryon reports.24 Whitehurst later died.

Simpson, wounded in the right shoulder, escaped for several weeks before he was captured and tried in Wilmington. He was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to having an “M” burned into his left hand.

Continue in the direction you were walking to the farthest grave.

Bostonian William Hill, a Harvard graduate, moved here in 1757 to run the town school, but soon became an import-export merchant partnered with the son of Richard Quince. Hill married Nathanial Moore’s daughter Margaret at Orton. He helped run the church here, and as a “lay reader” often ran the services when the minister was at others.25

Hill was appointed by Dobbs to collect taxes on alcoholic beverages. But as rebellion brewed, his attitude toward Britain changed. A 1773 visitor from Boston described Hill as “‘a sensible, polite gentleman, and though a crown officer, a man replete with sentiments of general liberty…’”26

Hill was surprised to receive a tea shipment the next August, given that the colony had adopted Boston’s embargo. He sent a letter to his supplier in England. He had ordered it for arrival a year earlier, but “‘it is now too late to be received in America. If I were… willing to take it, the people would not suffer it to be landed. Poison would be as acceptable.’” He returned the tea on the same ship.27

During the Revolution he moved to Wilmington and held government administrative roles, until dying in 1783 “‘of obstinate quackery,’” someone wrote at the time. He refused to call a doctor until “‘four days before his death.’”28

Armed Conflict Begins

Go back to your vehicle and drive toward the exit gate. Take the right turn just before the gate. A short drive takes you to a dirt lane on the right. (If you miss it, the road loops back at the end.) Under a protective roof is the remains of Russellborough, named for its first owner.

Park nearby and go to the ruins using the sidewalk next to the handicapped parking spaces—otherwise you risk getting covered in sand spurs!

Finished around 1760, here during the Revolution is a 45-by-35-foot home with four rooms on each of two floors, according to its third occupant, Gov. Tryon. Four months after taking the oath of office in April 1765, Tryon writes someone, “‘As you are acquainted with Mrs. Tryons (sic) Neatness you will not wonder that we have been pestered with scouring of Chambers, White Washing of Ceilings, Plaisterers (sic) Work, and Painting the House inside and out.’”29 There are ten-foot-wide porches all the way around both stories, with four-foot-high railings, “‘which is a great Security for my little girl,’” Tryon says. In the back left corner of the lower porch is a privy, above a down-sloping tunnel to the river: a rare colonial sewer!30

Finished around 1760, here during the Revolution is a 45-by-35-foot home with four rooms on each of two floors, according to its third occupant, Gov. Tryon. Four months after taking the oath of office in April 1765, Tryon writes someone, “‘As you are acquainted with Mrs. Tryons (sic) Neatness you will not wonder that we have been pestered with scouring of Chambers, White Washing of Ceilings, Plaisterers (sic) Work, and Painting the House inside and out.’”29 There are ten-foot-wide porches all the way around both stories, with four-foot-high railings, “‘which is a great Security for my little girl,’” Tryon says. In the back left corner of the lower porch is a privy, above a down-sloping tunnel to the river: a rare colonial sewer!30

The first floor is five feet off the ground, though there is a cellar, which you see today. Nearby to the left are a stable, coach house, and other outbuildings. In the garden are various fruit trees, Tryon says: apple, fig, nectarine, peach, and plum.31 Between the house and the river, canals are cut into the marsh to drain it for rice patties.32

Probably where the walkway to the house is now, in colonial times a tree-lined lane extends straight from the front door through farm fields on both sides, continuing to the road from Wilmington.

The Revolutionary War history of Brunswick Town started here, and in one sense, that of all the colonies. In 1766—seven years before the famous Boston Tea Party—a thousand people33 led by the area Sons of Liberty arrive at this spot to protest the Stamp Act. This law by the British Parliament said all printed materials in North America had to carry a government stamp, bought with a tax, to help pay off the costs of the French & Indian War. That tax had long existed in England, but previously, only colonists’ elected assemblies had taxed them. Also, the law said violators could be tried in British navy courts, instead of local courts with juries of their peers.

A British vessel stationed off the mouth of the river had seized three incoming merchant ships for violating the Act. Wilmington refused to supply it. On Monday, February 19, around 150 armed men from the larger crowd surround the house. They trap Gov. Tryon and a number of colonial officers inside, thinking the warship’s captain is among them. They back off when someone they trust confirms he is still on the vessel.34

The next day the captain agrees to release the seized ships, but the protesters aren’t done. They round up two customs officers, responsible for enforcing the Stamp Act.

Tryon tells in a letter what happens the next morning. Around 10 a.m. on Wednesday, 580 men, most armed, approach the house, stopping about three American football fields away. Sixty of them, led by Cornelius Harnett, a member of the Provincial Assembly, come here to the door. Harnett asks to speak to the customs officer. Tryon replies, “‘Mr. Pennington came into my house for refuge, he (is) a Crown Officer, and as such I would give him all the protection my roof and the dignity of the character I held in this Province, could afford him.’ Mr. Harnett hoped I would let him go, as the people were determined to take him out of the house if he should be longer detained; an insult he said they wished to avoid offering to me…”35 Tryon points out this would not add much insult after they have already surrounded his house, “making me in effect a prisoner…” Pennington tells Tryon he will go, but Tryon convinces him, over Harnett’s objection, to resign first.36 The three customs officers are escorted into town, where they pledge never to enforce the Act.

Though Virginia had passed resolutions against the Act, and Sons of Liberty in northern cities had held angry demonstrations, this was the first armed action directed against Parliament in America.

Tryon moved to New Bern in 1770, and William Dry bought the house. Five years later, Tryon’s replacement Josiah Martin fled New Bern for Fort Johnston. Wisely, he bypassed Brunswick Town. When he later hired one of the townsmen as a courier, “This messenger proved untrustworthy and promptly handed over his information to the Whigs” (Patriots).37

The committees of safety in the area order their militia to take back the fort. By Saturday, July 15th, 1775, 500 men have rendezvoused in Brunswick Town, probably right here.38 They march south to start the American Revolution in North Carolina by burning the fort.

The mansion came to the same end. The Virginia Gazette reported in April 1776 that likely church-burner Collett “‘set fire to the elegant house of Col. Dry, destroying therein all the valuable furniture, liquors, etc.’” It continued, “‘The Town of Brunswick is totally deserted, and the enemy frequently land in small parties, to pillage and (to) carry off” enslaved people.”39

Archaeologists found “thousands of fragments of wine bottles” under the left-side porch, plus 158 of Dry’s bottle seals, indicating that this was the part of the cellar where the “valuable… liquors” were stored and burned, 300 bottles or more.40

As noted above, Brunswick had already been surpassed by Wilmington as a port. Though the town was reoccupied, it never recovered and was completely abandoned by war’s end.

Casualties

- April 1776:

- British: 0.

- Patriot Militia: 6 captured.

- May:

- British: 1 killed.

- Patriot Militia: 0.

Historical Tidbits

As part of a decades-long argument between England and Spain over the Carolinas, Spanish privateers—pirates legally sanctioned by Spain—attacked here on September 4, 1748. A local historian says they had stopped at Fort Johnston, but it was Sunday, so apparently everyone was here for church!41 Cannon fire from the three ships, and musket shots from a ground force offloaded downstream, announced their arrival. The privateers pillaged homes, stores, and docked merchant ships until the town’s militia commander pulled together around 60 men, a third of them Black.42 They snuck into town as the Spanish were loading stolen goods onto a captured English ship, and drove them offshore. One of the privateer ships blew up by accident and sank while firing on the militia. A cannon almost certainly from that ship is displayed at the Visitor Center.

As part of a decades-long argument between England and Spain over the Carolinas, Spanish privateers—pirates legally sanctioned by Spain—attacked here on September 4, 1748. A local historian says they had stopped at Fort Johnston, but it was Sunday, so apparently everyone was here for church!41 Cannon fire from the three ships, and musket shots from a ground force offloaded downstream, announced their arrival. The privateers pillaged homes, stores, and docked merchant ships until the town’s militia commander pulled together around 60 men, a third of them Black.42 They snuck into town as the Spanish were loading stolen goods onto a captured English ship, and drove them offshore. One of the privateer ships blew up by accident and sank while firing on the militia. A cannon almost certainly from that ship is displayed at the Visitor Center.- During the Civil War, Confederates built breastworks on the old town site and named it Fort Anderson. It fell to Federal troops after a naval bombardment and three-day battle in February of 1865. Fittingly, it then was used by the U.S. Freedman’s Bureau as the largest camp in the Cape Fear area for refugees from slavery, until 1867.43

More Information

- Angley, Wilson, A History of Fort Johnston on the Lower Cape Fear (Southport, N.C.: Southport Historical Society, 1996)

- Barefoot, Daniel. 1998. Touring North Carolina’s Revolutionary War Sites. Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher.

- “Brunswick Town and Fort Anderson: History.” n.d. North Carolina Historic Sites. Accessed February 2, 2020. https://historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/brunswick-town-and-fort-anderson/history.

- Butler, Lindley, North Carolina and the Coming of the Revolution, 1763-1776 (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, 1976)

- DiNome, William. 2006. “Brunswick Town.” NCpedia. 2006. https://www.ncpedia.org/brunswick-town.

- Dunkerly, Robert M., Redcoats on the Cape Fear: The Revolutionary War in Southeastern North Carolina, Revised (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2012)

- Ferrell, Allan, Burnswick Town Tour and Interview, 2024

- Fonvielle, Chris, ‘With Such Great Alacrity’, North Carolina Historical Review, XCIV.2 (2017)

- Grant, Dorothy, ‘Smith, Benjamin’, NCpedia, 1994 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/smith-benjamin> [accessed 31 October 2020]

- Lee, Lawrence, The Cape Fear in Colonial Days (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1965)

- Lee, Lawrence, The History of Brunswick County, North Carolina (Brunswick County [via Heritage Press, Charlotte, N.C.])

- Lefler, Hugh, ed., North Carolina History: Told by Contemporaries (The University of North Carolina Press, 1948)

- Lewis, J. D. 2007. “A History of Brunswick Town, North Carolina.” 2007. https://www.carolana.com/NC/Towns/Brunswick_Town_NC.html.

- Lewis, J. D. 2009. “Brunswick Town.” The American Revolution in North Carolina. 2009. https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_brunswick_town_2.html.

- Lewis, J. D. 2010. “Brunswick Town.” The American Revolution in North Carolina. 2010. https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_brunswick_town_1.html.

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Governor of the State of North Carolina – Benjamin Smith’, Carolana, 2007 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Governors/bsmith.html> [accessed 31 October 2020]

- London, Lawrence, ‘Hill, William’, NCpedia, 1988 <https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/hill-william> [accessed 10 December 2024]

- ‘Marker: D-85’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=D-85> [accessed 31 October 2020]

- McKee, Jim, Brunswick Town & Fort Anderson Historic Site, In-person interviews, 10/6/2020 & 11/26/24

- Miles, Natasha. 2016. “Brief History of Brunswick County NC.” NCGenWeb, 2016. http://www.ncgenweb.us/brunswick/history.html.

- Rankin, Hugh F., ‘The Moore’s Creek Bridge Campaign, 1776’, The North Carolina Historical Review, 30.1 (1953), 23–60

-

Schaw, Janet, and Evangeline Walker Andrews, Janet Schaw, ca. 1731-ca. 1801. Journal of a Lady of Quality; Being the Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the Years 1774 to 1776. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1921) <https://www.docsouth.unc.edu/nc/schaw/schaw.html> [accessed 7 January 2021]

- South, Stanley, Archaeology at Colonial Brunswick (Office of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 2010), Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill <https://uncpress.org/book/9780865263437/archaeology-at-colonial-brunswick/> [accessed 28 June 2024]

- South, Stanley A., ‘Searching for Clues to History Through Historic Site Archaeology’, The North Carolina Historical Review, 43.2 (1966), 166–73

- Thompson, Roy, Before Liberty: Their New World Made The North Carolinians Different (Lexington, N.C.: Green Printing Company, Inc., 1976)

- Tryon, William, ‘Letter from William Tryon to Henry Seymour, Volume 07, Pages 169-174’, Documenting the American South: Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, 1766 <https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr07-0067> [accessed 30 July 2024]

- ‘Virginia Gazette: Dixon and Hunter, Jan. 13, 1776, Pg. 3’, The Colonial Williamsburg Official History & Citizenship Site <https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/va-gazettes/VGSinglePage.cfm?issueIDNo=76.DH.03&page=3&res=LO> [accessed 3 December 2024]

- ‘Virginia Gazette: Dixon and Hunter, June 29, 1776, Pg. 2’, The Colonial Williamsburg Official History & Citizenship Site <https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/va-gazettes/VGSinglePage.cfm?issueIDNo=76.DH.28&page=2&res=LO> [accessed 9 December 2024]

- Walker, Shannon, Brunswick Town & Fort Anderson Historic Site, Phone interview, 10/29/2020

- ‘William Henry Hill (1737–1783)’, FamilySearch <https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/LJZR-WYP/william-henry-hill-1737-1783> [accessed 10 December 2024]

1 DiNome 2006.

2 South 1966.

3 Dunkerly 2012.

4 South.

5 Sprunt (Chronicles of the Cape Fear River, 1914) based on the Custom House entry book for 1773–76.

6 South.

7 Lewis 2009.

8 Southern part and its location: McKee 2020, Walker 2020.

9 The mistake probably arose from an article in the Virginia Gazette of November 1776, which reports the raid and says the British are “expected to have burned” the town. A British officer says they intended to, but then found it abandoned, implying they did not burn it. A Loyalist force burned a couple of buildings that year as described later, but Site Manager Jim McKee (2024) said a visitor the following year indicated the rest of the town was intact. Uniform buttons from two regiments that were in Wilmington in April 1781 were found here by archaeologists. This suggests a detachment came here at that time. No newspapers reported the burning of the town at any point in the war, however, so the culprits and correct date may never be identified.

10 Ferrell 2024.

11 Pedlow.

12 Lee 1980.

13 DiNome 2006.

14 Quotes from: Schaw & Andrews 1921.

15 South reports a claim that Quince met celebrated Loyalist Flora MacDonald*. But the story of her selling silver to him to pay for her passage on one of Quince’s ships is a myth: Her son-in-law came to get her and his family in a ship he hired up North. Also, the silverware in question was inscribed “R (large M) Q.” The meaning of the M remains a mystery, but it was never there by itself, so it didn’t stand for MacDonald. Furthermore, the will of Quince’s son said nothing about the silver being from MacDonald, and MacDonald says in her memoir her tableware was stolen by Patriot raiders.

16 Farrell 2024.

17 Watson 1968.

18 Reaves 1988.

19 Thompson 1976.

20 South.

21 Ibid.

22 Walker.

23 McKee 2020.

24 Tryon 1765. Moore (1956) relays an oral tradition that the duel was held in the woods beyond this side of town, in the area of the church.

25 Judah 2008.

26 London 1988.

27 Quoted in Lefler 1948.

28 Quoted in London.

29 Tryon 1765.

30 Quotes and privy from South.

31 Dunkerly.

32 South.

33 Butler 1976.

34 Butler.

35 Commas removed for clarity.

36 Tryon 1766.

37 Rankin 1953.

38 McKee 2020.

39 Quoted in South.

40 Lefler 1948.

41 Angley 1996; Fort Johnston anecdote: Fonvielle 2017.

42 Fonvielle.

43 McKee, Jim, ‘Fort Anderson Labor’, E-mail, 2/3/2020.

← Fort Johnston | Cape Fear Tour | Wilmington →