Patriots Destroy a Village and its Families

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.2698, -83.1228.

Type: Sight

Tour: Cherokee

County: Jackson

![]() Full

Full

The coordinates point to a small parking lot on the east side of Highway 107. Turn your vehicle to face across the highway, parallel to Granite Cliff Drive, and you can see everything described at this location.

Context

Cherokees hoping to regain their lost lands continued to raid European-American settlements throughout the Revolutionary War, triggering military campaigns in response.

Cherokees hoping to regain their lost lands continued to raid European-American settlements throughout the Revolutionary War, triggering military campaigns in response.

Situation

Cherokee

Despite continued tensions, residents of the isolated village of Tuckaseegee[1] probably were not participating in the attacks and felt protected by mountains few whites had traversed. They went about their daily lives.

Patriot

Col. John Sevier of the Washington County Militia Regiment, part of the Overmountain Men who won the Battle of King’s Mountain (S.C.), mustered a small force to punish the Cherokees by attacking their “Middle Towns” within the mountains. Washington County, part of N.C. at the time, was in today’s Tennessee. Sometimes the men are forced to dismount and lead their horses over the formidable mountain passes. The first town they reach is Tuckaseegee.

Date

March 1781 (exact date unknown).

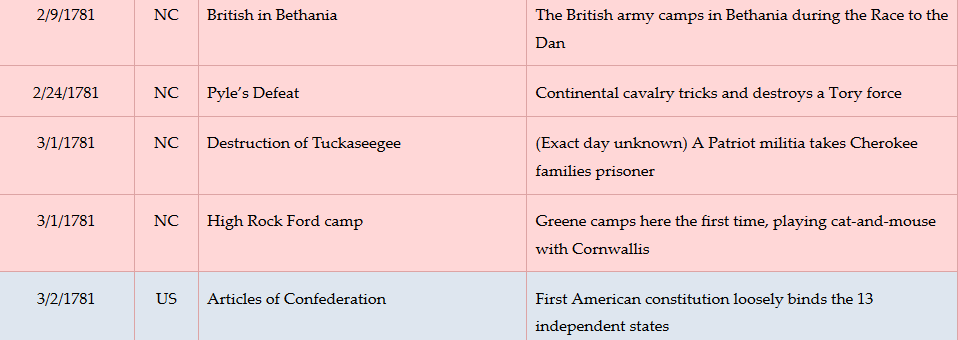

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

Look at the commercial area across the highway, in the bend of the Tuckaseegee River.

In March 1781, you are looking at the Cherokee town of Tuckaseegee. A book of Cherokee stories says the original word may have meant “mud turtle place,” as turtles were common here. It suggests this was one of the earliest Cherokee settlements in this region, perhaps dating as early as 1,000 C.E. The village became known as “‘the place they rode backward.’” By sitting at the fork where the West Tuckaseegee, to the right across the bridge, joined the main river, and staring into the water, you could get the sensation of moving upstream![2]

In March 1781, you are looking at the Cherokee town of Tuckaseegee. A book of Cherokee stories says the original word may have meant “mud turtle place,” as turtles were common here. It suggests this was one of the earliest Cherokee settlements in this region, perhaps dating as early as 1,000 C.E. The village became known as “‘the place they rode backward.’” By sitting at the fork where the West Tuckaseegee, to the right across the bridge, joined the main river, and staring into the water, you could get the sensation of moving upstream![2]

One house here is “round and twenty-three feet in diameter. The four outer wall posts (are) set four feet apart” with another set inside for roof support. “A fire basin (is) located in the center… and the smoke hole above the basin (is) made of clay plaster to protect the roof.”[3] Somewhere there is a larger council house (townhouse); other circular homes or log cabins surrounded by fallow farm fields; round sweat lodges of vertical logs; and livestock pens. A granary holds the fall harvest.

Look toward the church, in the distance uphill to the north.

Sevier’s force is approaching down the Tuckaseegee Valley from the direction of modern Webster, the route now marked by NC 107. Because of the hill on that side of town, the Cherokees probably have no warning of the army’s approach—both the view and vibrations that might have been felt on flatter ground are blocked by it. Instead, the first sign of the 130-170 part-time soldiers called “militia” is likely their appearing over the hill at a gallop. They wear standard backwoods clothing, not uniforms, and carry long guns and perhaps some swords.

There are no eyewitness details, but we can speculate on the action based on both sides’ military practices and the casualty counts. Cherokee men and women probably rush out of the homes and townhouse trying to prepare their muskets, firing at the marauders as soon as they can. The horsemen with swords go after individual warriors who fight back with gun barrels and war clubs. Other militia probably pull up their horses and begin firing back, some dismounting. But surprise and superior numbers have won the day, so eventually the surviving Cherokees lay down their weapons.

Taken captive, the villagers are forced to watch as Sevier’s men light torches and burn all of the buildings. The Cherokees then are marched off with the army as it heads south across the river, probably to be sold as slaves.

Casualties

- Cherokee: 17 to 50 killed, unknown wounded, at least 28 warriors plus around 50 women and children captured.

- Militia: 1 killed, 1 wounded.

After the Battle

Sevier’s force continued downriver and destroyed between six and 20 villages (eyewitness sources vary).

The structure the archaeologists found had been burned. Clay insulation from the roof hole lay atop the fire pit in the floor. The modern industrial building appears to cover it now.[4]

Historical Tidbits

- In 1751 residents of the Cherokee town of Keowee (S.C), angered by cheating traders and fearing rumored attacks by colonial governments, asked other villages to attack traders throughout their lands. Only Stecoah (in today’s Whittier) responded, raiding the home of their local trader, Bernard Hughes. However, his Cherokee mistress warned him, and he and three others escaped here to Tuckaseegee.[5]

(AmRevNC photograph) A short drive from this stop is Judaculla Rock, boasting the highest concentration of Native American petroglyphs east of the Mississippi River. Petroglyphs are symbols etched or carved into rock, and this set dates back to at least 500 C.E. The soapstone rock was quarried for bowls as many as 3,500 years ago (see the lower right corner of the photo). A Cherokee story holds that a giant named Tsul Kalu steadied himself with his hand there, leaving the marks, after jumping 10 miles in pursuit of hunters who had not performed the required rituals. If you visit, please do not touch the rock, a Cherokee sacred space, to preserve it for future generations. To visit the rock, head north about 3 miles. Watch for a state historical marker and green highway sign for the rock on the right. Turn right onto Caney Fork Road (County Road 1737) and drive 2.5 miles, following similar signs to Judaculla Road. Turn left and drive a half-mile to the end. Take the short, full access trail on the right to the rock (coordinates: 35.3017, -83.1101).

More Information

- Corkran, David H., ‘The Unpleasantness at Stecoe’, The North Carolina Historical Review, 32.3 (1955), 358–75

- Duncan, Barbara R., and Brett H. Riggs, Cherokee Heritage Trails Guidebook (Chapel Hill: Published in Association with the Museum of the Cherokee Indian by the University of North Carolina Press, 2003)

- Gulahiyi, ‘The Destruction of Tuckasegee?’, Ruminations from the Distant Hills, 2008 <https://gulahiyi.blogspot.com/2008/12/destruction-of-tuckasegee.html> [accessed 8 April 2020]

- ‘Judaculla Rock Petroglyphs’ (Marker, Cowarts, NC)

- Keel, Bennie, Cherokee Archaeology: A Study of the Appalachian Summit (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1976)

- Middleton, T. Walter, Qualla, Home of the Middle Cherokee Settlement: Tales of the Great Smoky Mountains’ Native Americans (Alexander, N.C.: WorldComm, 1999)

- ‘Marker: Q-4’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=Q-4> [accessed 31 August 2020]

- Rozema, Vicki, Footsteps of the Cherokee: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation, Second ed. (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 2007)

- Smith, Betty Anderson, ‘Distribution of Eighteenth-Century Cherokee Settlements’, in The Cherokee Indian Nation: A Troubled History, ed. by Duane H. King (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1979)

- Ward, H. Trawick, and R. P. Stephen Davis, Time Before History: The Archaeology of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999)

[1] Some modern sources claim Tuckaseegee was in today’s Webster. Two Cherokee guidebooks (Duncan & Riggs 2003, Rozema 2007), and Cherokee storyteller Old Wayah (per Middleton 1991), place it here. Two archaeology books agree (Keel 1976, Ward & Davis 1999). Finally, a comprehensive review of Cherokee town sites shows Tuckaseegee as the farthest upstream on this river (Smith 1979). Note that only villages large and permanent enough to have council houses were referred to by the Cherokee word translated as “town.”

[2] Middleton.

[3] Rozema 2007; though she calls this the townhouse, an archaeology book (Ward & Davis 1999) says most scholars up to that time agreed it was too small.

[4] Keel 1976.

[5] Corkran 1955.