Two Cherokees are Scalped

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.4210, -83.3476.

Type: Sight

Tour: Cherokee

County: Jackson

![]() Full

Full

There is no good place to park where the primary action of this page occurred. Small vehicles can fit into the public right-of-way at the entrances to two farm lanes on either side of Thomas Valley Road near the coordinates. Though best viewed facing west (toward Whittier), this is close to a rail spur line, so be cautious.

Larger vehicles will have to drive by the coordinates going west to get a quick look, noticing the far corner between the lines of trees on the western and back sides of the farm field. Continue to the first paved road on the right, Clearwood Drive, and park where you can see all the way across the wide field you just passed to the same line of trees from the other side.

Context

Cherokees fighting American expansion into their lands launched raids in May 1776, leading to state campaigns that destroyed dozens of towns that September.

Cherokees fighting American expansion into their lands launched raids in May 1776, leading to state campaigns that destroyed dozens of towns that September.

Situation

Cherokee

Aware of the approach of another North Carolina state force, Cherokee soldiers and their families are withdrawing from indefensible villages along the Tuckaseegee River.

Continental/Patriot

Brig. General Griffith Rutherford, who led the September invasion for North Carolina, ordered his brother-in-law Capt. William Moore to make another raid along a more northerly route with his cavalry company. Moore joined up with another company at Cathey’s Fort (north of Marion) and headed over the Swanannoa Gap by modern Asheville. Moore seems to have followed the same path as the September campaign at least as far as modern Waynesville. But he took a different route across the ridge line to the west, using a, “Very plain path, Very much used by indians [sic]” to the Tuckaseegee.[a]

Date

Friday, November 1, 1776.

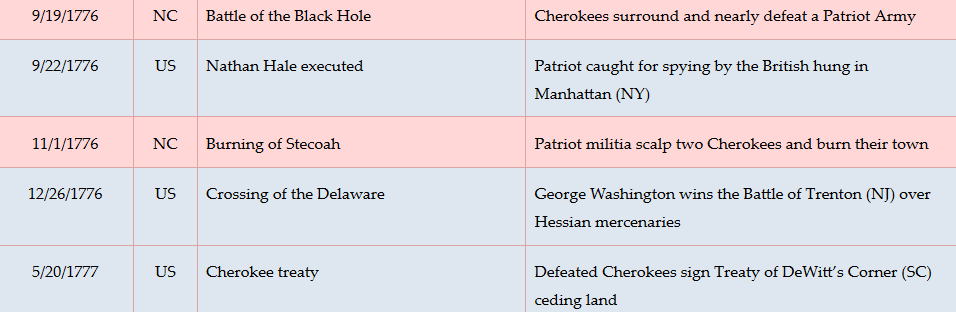

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

Rushing into Town

Though the basic facts are supported by other sources, all details of this attack come from a single source, Moore’s report to Rutherford written on November 17. Believe with caution!

Though the basic facts are supported by other sources, all details of this attack come from a single source, Moore’s report to Rutherford written on November 17. Believe with caution!

The river is just on the other side of the trees that border the back sides of the farm fields. Look toward the line of trees between the fields, mentioned under “Location,” which mark a small stream emptying into the river.

Located near the river on the east side of the stream, you see the Cherokee village of Stecoah (pronounced “steh-KOH-ah”[1]). A book of Cherokee stories says the name might mean “the baby one,” referring to the parent village of Kituwah six miles upstream. Cherokees at times called themselves ani-Kituhwagi or “people of Kituhwa.”[b] The book says Stecoah may have been hundreds of years old by the time of the Revolution. Sometime in its early history, a story claims, a massive flock of birds chose to roost here one night. So many landed that buildings and homes collapsed. A number of residents, including entire families, were killed. Survivors joined hands and pushed through the flock to the river to escape.[c]

Prominent in 1776 is a larger round council house, or rather the finished walls, probably near the stream and river. The roof is not yet covered. About 25 log homes surround it. Fallow farm fields spread to the west along the river. What is missing is people, except for two, possibly left as caretakers or messengers in case the rumored invasion doesn’t come.

When the milita came within sight of the town, they halted to discuss how to attack it. Moore describes it as, “Very scattered.” This suggests it followed a typical layout of Cherokee towns, in which homes surrounded by farms spread out from a central townhouse, with paths in between. With only 97 men, they could not surround it. In the end, they “rushed into the Centre of the town, in Order to surprise it.”

Look down the tracks to the east (away from Whittier).

A trading path runs near or where the rails run today. First you hear the sound of galloping horses. Then you see the soldiers riding straight into town. These are part-time “militia” soldiers in everyday clothes carrying muskets or rifles.

The two Cherokees run for the river and dive in. Some of the horsemen ride to the bank and aim. As the Native men climb out on the other side, the militia fire, and one escapee falls dead. The other sprints up a hill. A few of the militia dismount and plunge into the river; a few others ride to a nearby ford (toward modern Whittier), and catch him in the far distance. Meanwhile one of the militia soldiers who swam across kneels down and scalps the dead man. The other was scalped as well.[2]

While that happens, the regiment spreads across the flats (in the direction of Clearwood Drive) and plunders the homes.

The residents had taken the most valuable items with them, “save corn, pompions (pumpkins), beans, peas and other trifling things of which we found in abundance in every house,” Moore reports. They take the corn and the “trifling things” they want. Torches are lit, and all of the buildings are set afire. The militia then ride to the ford and continue north.

After the Raid

The militia found and followed the path the two Cherokees were trying to reach. Seeing a fire on Hogback Mountain directly north, an advance party including Moore crossed the mountain and found evidence of Native camps. They went back for the rest of the men, and then probably went as far as the Little Tennessee River, now Fontana Lake. Chasing two women and a boy, one of the men fired a gun, which warned the camps in the area and sent the refugees farther into the mountains. The militia captured the trio and found more plunder and horses. Among the latter were some stolen from white settlers, which they eventually returned.

Short on supplies, they headed home. While camped on an unknown mountain that night, they experienced “a Severe Shock of an Earthquake.” It took two days to get to the road back to Richland Creek, from there going on to Pigeon River. After a dispute there described on that page, the prisoners were sold into slavery for £272, part of a total from all plunder of £1,100 (around $174,000 today).[d]

Casualties

- Cherokee: 2 killed.

- Militia: 0.

Historical Tidbits

In 1751, residents of the town of Keowee in South Carolina, angered by cheating traders and fearing rumored attacks by colonial governments, asked other Cherokees to attack traders throughout their nation. However, from the Cherokee perspective, Keowee was a frontier town prone to more friction with the British. Only Stecoah responded, raiding the home of their local trader, Bernard Hughes. However, his Native mistress warned him, and he and three others escaped south to Tuckaseegee. A respected leader named The Raven sent his son with a demand that Stecoah return Hughes’ goods. He found the town deserted and soon received word the residents had fled when they realized they acted alone! The residents returned everything except about “400 lbs. weight of deerskins and £50 or £60 value of goods damaged in the looting…”[3]

In 1751, residents of the town of Keowee in South Carolina, angered by cheating traders and fearing rumored attacks by colonial governments, asked other Cherokees to attack traders throughout their nation. However, from the Cherokee perspective, Keowee was a frontier town prone to more friction with the British. Only Stecoah responded, raiding the home of their local trader, Bernard Hughes. However, his Native mistress warned him, and he and three others escaped south to Tuckaseegee. A respected leader named The Raven sent his son with a demand that Stecoah return Hughes’ goods. He found the town deserted and soon received word the residents had fled when they realized they acted alone! The residents returned everything except about “400 lbs. weight of deerskins and £50 or £60 value of goods damaged in the looting…”[3]- One of the most important names in Cherokee history is William Holland Thomas, a European-American adopted as a child by Cherokees who rose to become the chief of the Eastern Band. He negotiated permission for them to stay in North Carolina after the rest of the tribe was forced to move to Oklahoma; bought the land that became the Qualla Boundary (reservation); and led a regiment of Cherokees in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. His home was here, on the exact site of the council house.[4]

More Information

- Beadle, Michael, ‘Rutherford Trace: Local Historians Examine the Legacy of a Shock-and-Awe Revolutionary War Campaign against the Cherokee’, Smoky Mountain News, 2006 <https://www.smokymountainnews.com/archives/item/13169-rutherford-trace-local-historians-examine-the-legacy-of-a-shock-and-awe-revolutionary-war-campaign-against-the-cherokee> [accessed 5 April 2020]

- Corkran, David H., ‘The Unpleasantness at Stecoe’, The North Carolina Historical Review, 32.3 (1955), 358–75

- Cucumber, Devin, Cherokee History, In-person interview, Cherokee, N.C., 8/27/2020

-

Dean, Nadia, A Demand of Blood: The Cherokee War of 1776 (Cherokee, N.C.: Valley River Press, 2012)

- Middleton, T. Walter, Qualla, Home of the Middle Cherokee Settlement: Tales of the Great Smoky Mountains’ Native Americans (Alexander, N.C.: WorldComm, 1999)

- Mooney, James, Myths of the Cherokee (New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1995) <https://books.google.com/books?id=YU9LpoZq5EwC&lpg=PA49&dq=rutherford%20expedition%20north%20carolina&pg=PP5#v=onepage&q=rutherford%20expedition%20north%20carolina&f=false>

- Moore, William, ‘Rutherford’s Expedition Against the Cherokees’, North Carolina University Magazine, February 1888, 89–93 (Museum of the Cherokee Indian Archive, 2010.253.0207, Rutherford Expedition: Miscellaneous)

- Rozema, Vicki, Footsteps of the Cherokee: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation, Second (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 2007)

- Smith, Betty Anderson, ‘Distribution of Eighteenth-Century Cherokee Settlements’, in The Cherokee Indian Nation: A Troubled History, ed. by Duane H. King (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1979).

- Wilburn, Hiram, ‘Nununyi, the Kituhwas, or Mountain Indians and the State of North Carolina’, Southern Indian Studies, 2.2 (1950) <http://www.rla.unc.edu/Publications/NCArch/SIS_2_2.pdf> [accessed 10 April 2020]

[1] Cucumber 2020.

[2] Moore’s report to Rutherford, 1/17/1776, from Wilburn 1950.

[3] Corkran 1955.

[4] Maj. James Wilson, 1/23/1888 letter reporting conversation with Thomas, from Wilburn.

[a] Unless otherwise footnoted, all quotations are from Moore 1888.

[b] Smith 1979.

[c] Middleton 1999.

[d] Nye, Eric, ‘Currency Converter, Pounds Sterling to Dollars, 1264 to Present’ <https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm>.

← Cowee Mound | Cherokee Tour | Cherokee Museum →