Militia Cannot Stop the British Legion

Location

Other maps: Bing, Google, MapQuest.

Coordinates: 35.5866, -77.8114.

Type: Sight

Tour: Cape Fear

County: Wilson

A pullout between NC 58, Peacock Bridge Road, and the creek provides a decent view from within your vehicle. Due to a downhill slope there, you can get a better one with a short walk through the grass.

Context

After recuperating in Wilmington from the Battle of Guilford Court House, the main British army of the South under Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis is leaving the state in hopes of joining with other forces in Virginia.

Situation

British

The 160-man cavalry of Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton and some mounted infantry soldiers[1] are riding a couple days ahead of the rest of the army, clearing the intended route of any rebel opposition.

Patriot

The Pitt County Militia, part-time soldiers under Col. James Gorham, have mobilized to stop the British. (This area was part of Pitt at the time.)

Date

Sunday, May 6, 1781.

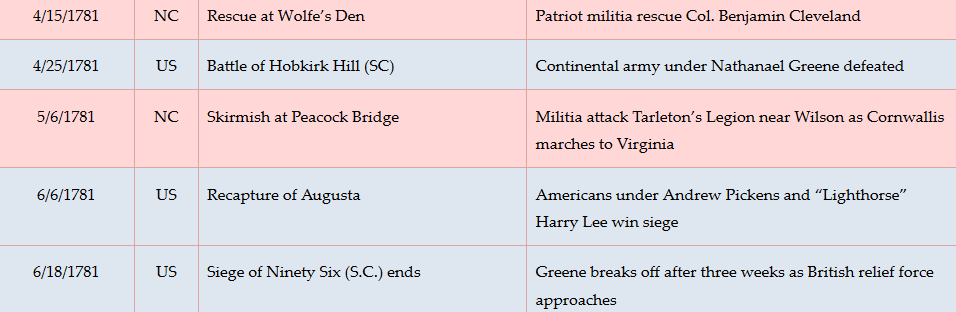

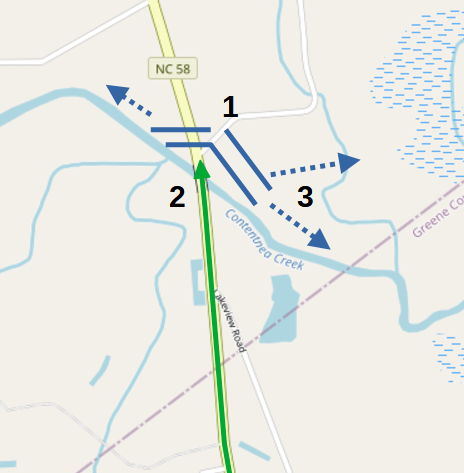

Timeline

Imagine the Scene

Walk behind the guardrail until you have a good view of the bridge and the highway into the distance.

In your mind’s eye, replace the modern bridge over Contentnea Creek with a sturdy wooden one. The creek was a highway for shipping goods to New Bern via flatboat, especially naval supplies like pine tar and turpentine.[2]

Starting in 1743, Samuel Peacock was granted this land and the tract on the far side, a total of 833 acres. First he operated a ferry here, but then he was licensed by the North Carolina Provincial Assembly to build a toll bridge, completed by 1751. Had you crossed then, you would have paid these government-approved rates:

“For every Man and Horse, Four Pence.

“For every Carriage, drawn by one or two Horses or Oxen, One Shilling.

“And for every Horse, Mare, or Ox, Four Pence each.

“And for every Head of Neat Cattle, One Penny.

“And for every Twenty Hogs or Sheep, One Shilling.”[3]

In current dollars, that’s about $4 per person, horse, or ox, and $12 for your carriage—or every 20 hogs![4]

Peacock lived on this side until he sold his land, and the bridge, to Samuel Ruffin three years later. Samuel moved to a tract next to his brother John’s. John owned the next bridge south, over Nahunta Creek or Swamp. So there was briefly a Peacock monopoly over this stretch of the route from Wilmington to Halifax![5]

In 1774, two years before he became the first governor of the new state of North Carolina, Richard Caswell paid 10 shillings to cross here heading up to Halifax.[6] Ruffin rebuilt the bridge the next year.[7]

The right to collect tolls under that earlier law ended in 1776 when the colony did, but Ruffin continued to charge them anyway. In fact, because the creek is fordable half the year, he dropped large trees along the creek bed on either side, to force people to use the bridge! In 1778, an indignant General Assembly took the franchise away from him. The assembly levied a fine of five pounds for each offense if Ruffin ever again charged someone for crossing the bridge, as the state felt he had been “more than abundantly reimbursed.” It also authorized another man to build a bridge over the creek. It is unclear from later maps whether that man replaced Ruffin’s with his or built another nearby first; regardless, that man has a third bridge at this spot in 1781. But reports from the Revolutionary War still called it “Peacock’s Bridge.”

On this side of the bridge on May 6, in the road and spreading out around you, are about 400 militia. These men are dressed in everyday clothes and carrying whatever weapons they own. They no doubt chat nervously as they wait, until a moving dot of green appears on the dirt wagon road (now NC 58) far to the south across the creek. They take positions as the dot grows into the approaching British Legion, heavy cavalry or “dragoons” wearing green jackets, followed by perhaps 50 Tories.[8] Most sources say Tarleton is with them. A Wilson County historian who traced the British march says Tarleton himself was upstream at Cobb’s Mill (later Wiggins’) near modern Wilson, but sent patrols out.[9]

Probably 100 yards or more from here—past the effective range of most weapons of the day—the horsemen draw sabres and charge. The militia fire at least one volley, but soon the British are on the bridge, and the Patriots lose heart. They scatter in all directions, most likely heading into the swamps or creek where the horses cannot follow.

After ensuring they have dispersed, the patrol continues up the road—presumably without paying any tolls! Tarleton must have been surprised whenever he learned the news, since the day before, he had written Cornwallis, “The Country is alarmed but the Militia will not turn out.”[10]

Battle Map

Skirmish at Peacock’s Bridge: Patriot positions are guesses for illustration. 1) Patriots await British approach at toll bridge. 2) British Legion, wearing green, charges. 3) Patriots fire a volley and scatter along creek or into swamps where horses cannot reach them.

Casualties

- British: Unknown wounded.

- Patriot Militia: Unknown wounded.

After the Battle

- A Tuscarora village was located upstream (to the right and behind you) in what now is Stantonsburg, one of at least 12 in today’s Wilson County.[11] The region was mostly abandoned by the Tuscaroras after they lost a four-year war with colonists in 1715.

- Cornwallis turned west at Nahunta Swamp, crossed Contentnea Creek at Cobb’s Mill, and camped in modern Wilson. He explained in a letter he was aiming for Halifax, the closest crossing point of the Roanoke River to his destination of Virginia. However, he said he was drifting westward from Wilmington in case the Continental Army came back to stop him. It had gone to South Carolina after failing to catch him at Ramsey’s Mill near modern Moncure. Apparently around this point he decides he is safe, because he soon turns more directly north.

More Information

- A History of Stantonsburg: Circa 1780 to 1980 (Stantonsburg Historical Society)

- ‘Contentnea Creek: History Exists Along It’s Waterway’, The Wilson Daily Times (Wilson, N.C., 20 October 1979)

- Darden, Cliff, ‘Greene County NcArchives Biographies…..Bridge, Speight’s’, USGenWeb, 2015 <http://files.usgwarchives.net/nc/greene/bios/bridge213bs.txt> [accessed 16 March 2020]

- Johnston, Hugh, ‘An Enlarged View of Wilson County During the Revolutionary War (Part Four)’, Undated, Wilson County Public Library, Local History and Genealogy Room, Vertical Files, ‘Wilson—History (pre 1850)’

- Johnston, Hugh, ‘An Enlarged View of Wilson County During the Revolutionary War (Part One)’, Undated, Wilson County Public Library, Local History and Genealogy Room, Vertical Files, ‘Wilson—History (pre 1850)’

- Johnston, Hugh, ‘An Enlarged View of Wilson County During the Revolutionary War (Part Three)’, Undated, Wilson County Public Library, Local History and Genealogy Room, Vertical Files, ‘Wilson—History (pre 1850)’

- Johnston, Hugh, ‘An Enlarged View of Wilson County During the Revolutionary War (Part Two)’, Undated, Wilson County Public Library, Local History and Genealogy Room, Vertical Files, ‘Wilson—History (pre 1850)’

- Johnston, Hugh, ‘When Cornwallis Passed through Wilson County’, Undated, Wilson County Public Library, Local History and Genealogy Room, Vertical Files, ‘Wilson—History (pre 1850)’

- Koown, Alex, ‘Bloody Banastre with Cornwallis’, The Wilson Daily Times (Wilson, N.C., 15 May 2004)

- Koown, Alex, ‘Indian Village Study Shows Multiple Sites in County’, The Wilson Daily Times (Wilson, N.C., 18 May 2007)

- Lewis, J. D., ‘Peacock’s Bridge’, The American Revolution in North Carolina, 2011 <https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/revolution_peacocks_bridge.html> [accessed 16 March 2020]

- ‘Marker: F-31’, North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program <http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=F-31> [accessed 16 March 2020]

- ‘North Carolina Gazetteer’, NCpedia <https://ncpedia.org/gazetteer/search/Contentnea%20Creek/0> [accessed 16 March 2020]

- Pierce, John, ‘Birds of a Feather’, Wilson County Public Library, Local History and Genealogy Room, Vertical Files, ‘Peacock’

- Rader, Douglas, ‘Into the Tuscarora Void: Early European Settlement in the Contentnea Creek Watershed of Wayne, Wilson and Greene Counties, North Carolina (Draft)’, Undated, Wilson County Public Library, Local History and Genealogy Room, Vertical Files, ‘Peacock’

- Rader, Douglas, and Elizabeth Peacock Rader, ‘A Peacock Odyssey: The Land Holdings in North Carolina of Samuel and Mary Peacock and Their Sons, John and Samuel’, 2007, Wilson County Public Library, Local History and Genealogy Room, Vertical Files, ‘Peacock’

- Tarleton, Banastre, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America (London : Printed for T. Cadell, 1787) <http://archive.org/details/historyofcampaig00tarl> [accessed 19 September 2020]

[1] Tarleton 1787.

[2] “Contentnea Creek.”

[3] Darden 2015.

[4] Nye, Eric, ‘Currency Converter, Pounds Sterling to Dollars, 1264 to Present’ <https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm>.

[5] Rader (Undated).

[6] Johnston, Part 1.

[7] Rader 2007.

[8] Johnston, Part 3.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Johnston, Part 2.

[11] Kwoon 2007.

← Kingston | More Tours